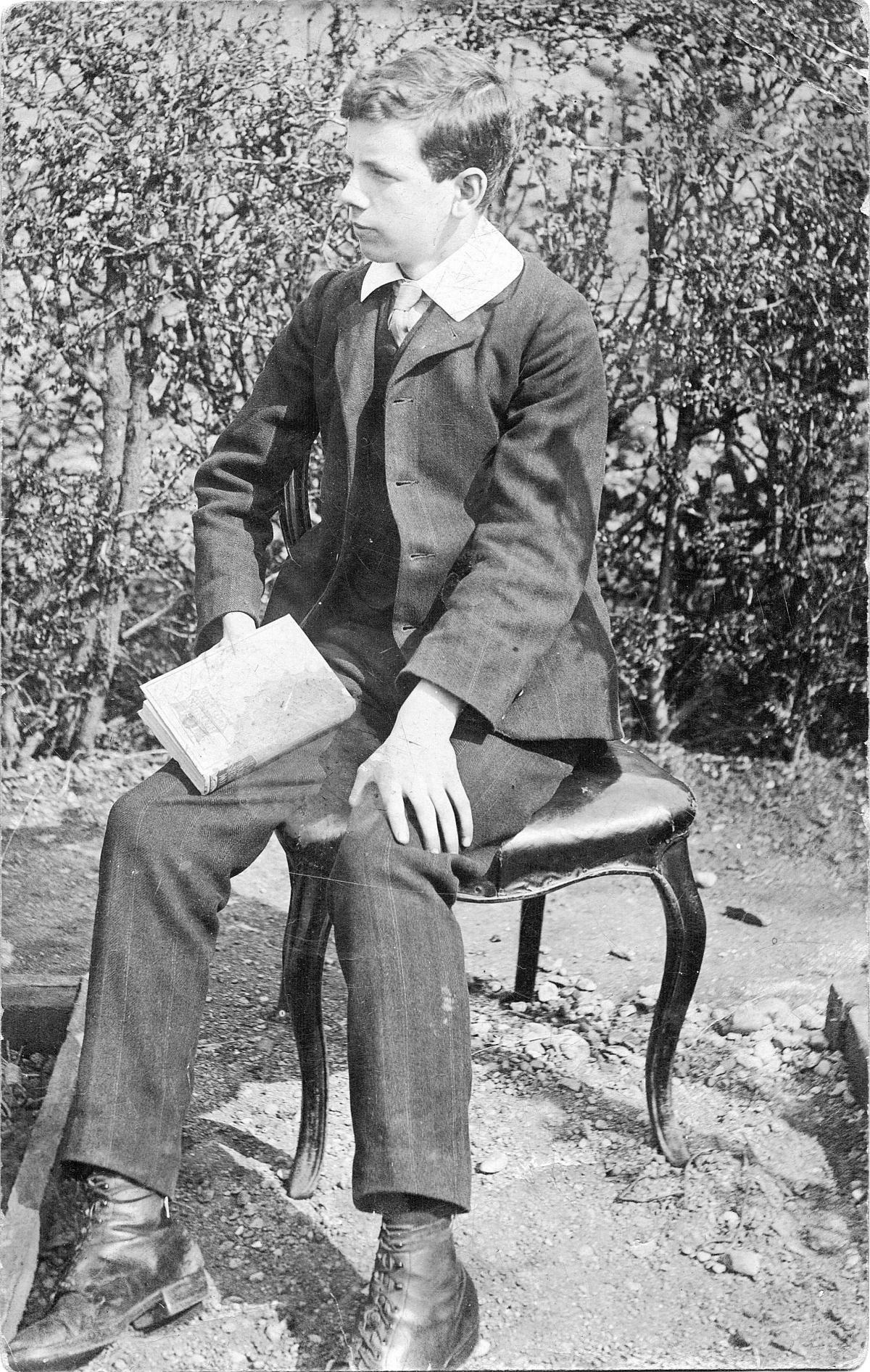

THERE'S a poignant photograph in Ken Haywood's new book The Lost Men of Bishopthorpe. It shows a young man with a freshly-scrubbed face sitting on a dining chair that has been set down outside somewhere, perhaps in a garden.

He's wearing what looks suspiciously like his Sunday best - suit, waistcoat and tie, with a large, starched shirt collar hanging over the lapel of his suit jacket.

In one hand, he's holding a favourite book. Look at the photograph very closely, and you can make out that it is a copy of Tom Brown's Schooldays.

The young man in that photo was called Frank Johnson. He was born in 1893 in Main Street, Bishopthorpe, and went to Bishopthorpe School and then Archbishop Holgate's. He was a keen sportsman, playing football, rugby and cricket both at school and later. He was a member of the church choir at St Andrew's in Bishopthorpe, and seems to have been good at his studies - as you'd guess, looking at that photograph.

Frank Johnson before he went off to war. Photo: A Doody/ The Lost men of Bishopthorpe

When he left school he - like his elder brother Wilfred - got a job as a civil servant with the Inland Revenue in Sheffield. There, in 1917 at the age of 24, he met and married his wife Margaret.

But this was wartime. Many civil service jobs were counted as 'reserved occupations'. But Frank was keen to do his bit, and volunteered for the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. He was mobilised on July 3, 1917, and in the following April, the last year of the war, he joined Hood Battalion of The Royal Naval Division, which was part of the British Expeditionary Force serving on the Western Front.

On August 21, 1918, Hood Battalion was given the task of capturing the village of Achiet le Petit near Arras. The war had entered its final exhausted weeks, but the Germans were not yet defeated, and were still putting up stiff resistance.

"Zero hour was 04.55 hrs," Ken writes in The Lost Men of Bishopthorpe. "A thick mist led to some units getting lost, including one of the tanks...In the initial stages there was little opposition from the German defenders, but desperate fighting was required to finally capture the village."

Between August 21 and August 28, Hood Battalion lost two officers and 38 men. Another officer and 38 men were recorded as missing in action. And six officers and 249 men were injured.

Among the injured was Able Seaman Johnson. He had been shot in the left thigh, and suffered a fractured femur. He was rushed to the British Red Cross Hospital at Wimereux near Boulogne. But despite having his leg amputated, his condition deteriorated. By September 10, he was described as 'dangerously ill' and his next of kin had been informed. On September 13, far away from those he loved, he died. He was 25, and had a son who was less than six months old.

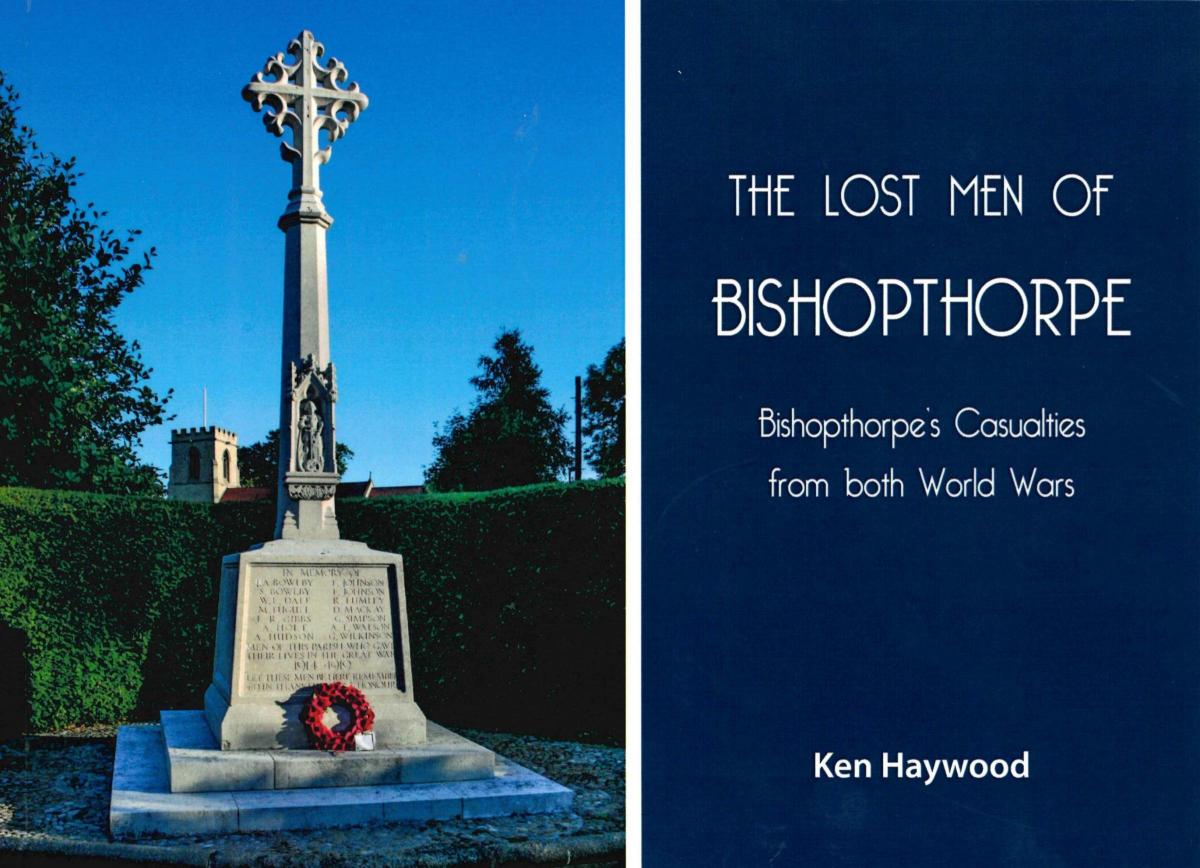

Ken Haywood at the Bishopthorpe War Memorial

Frank is one of 20 young Bishopthorpe men who lost their lives in the First World War and whose stories are told in Ken's new book. The book also tells the stories of 11 men who gave their lives during the Second World War.

Not all of these men's names are inscribed on the village's war memorial - six of the First World War men aren't there, as well as one of the men who died during the Second World War. Ken, a 71-year-old retired railway tunnel engineer and keen family historian who lives in Bishopthorpe, isn't sure why some were left off. But he was keen to tell as many of the stories as he could.

The last book which attempted to tell the story of the men commemorated on the memorial was former Dringhouses School head Claude Brayley's Lest We Forget, published in 1975. Mr Brayley was able to speak to local people who knew the men from both wars who had died.

But since his book was published, many First World War records which were closed in Brayley's time have been released. The Internet has also made research much easier, Ken points out - though he admits he couldn't have written his own book without the help of the families of those whose lives he has been researching.

His book aims to be a commemoration of the village men from Bishopthorpe who gave their lives in the First World War. They - like all those countless others from towns and villages up and down the land who were killed in the two world wars and other conflicts - deserve to be remembered, he says.

In the First World War, there was scarcely a family or a village in the country that was not affected in some way. One of his own great uncles was killed at Ypres; another was badly wounded on the Somme; a third was awarded the military cross during the Battle of Arras; and his paternal grandfather was gassed while serving with the Royal Field Artillery.

"At the very least, we owe it to the men who gave their lives not to forget them.," he says. "I often think how I would have reacted if I had been at Passchedaele or The Somme. It was such a sacrifice - for those men, and for their families as well. These men deserve to be remembered."

Below, we tell the story of some of the men from the First World War who are remembered in Ken's book. Next week, we'll look at some of those who gave their lives in the Second World War.

- The Lost Men of Bishopthorpe: Bishopthorpe's Casualties from Both World Wars by Ken Haywood will be published by K&L Publishing on November 8, priced £10. It will be available from York Explore libraries or direct from the author at kandlpublishing@yahoo.com for £10 plus £p&p. Any profits will go to the War Memorials Trust.

Meet some of the Bishopthorpe 'lost' men of the First World War

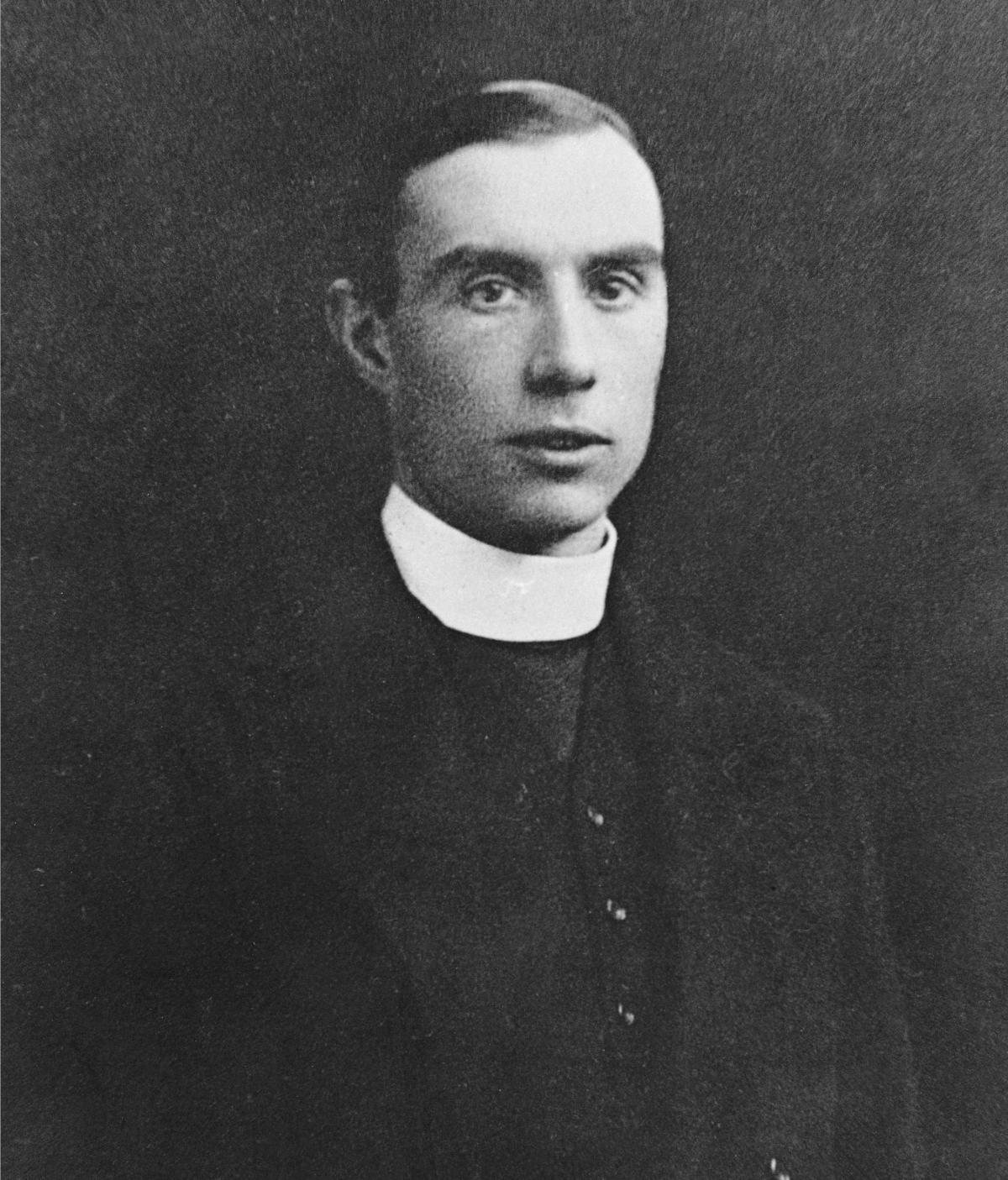

Rev Edward Reginald Gibbs

The Rev Gibbs was probably the highest-profile Bishopthorpe casualty of the war - until 1917 he was domestic chaplain to the Archbishop of York Cosmo Gordon Lang, as well as curate in charge of Bishopthorpe and Acaster Malbis. But several of his brothers were serving in the war, and an elder brother, Lt Col William Beresford Gibbs, had been killed in action. "No doubt Edward felt he should be doing his bit as well," writes Ken Haywood.

The Rev Edward Reginald Gibbs. Photo from The Lost Men of Bishopthorpe

In 1917 he volunteered as an army chaplain, and was attached to 1 Battalion of the Grenadier Guards on the Western Front.

He was killed in action on March 29, 1918, near Arras in France, aged just 32."He had been officiating at the burial of a soldier from his battalion near arras when a shell burst near him, killing him instantly," Ken writes.

Archbishop Lang was grief stricken at his death, and commissioned a wooden triptych in the chaplain's honour which still stands behind the altar in St Andrew's Church.

Ambrose Hudson

George Ambrose Hudson - who was always known as Ambrose - was the son of John Hudson, a railway signalman who controlled the trains and boats from the signal box which used to stand on top of Naburn Swing Bridge. The family lived in one of the railway cottages on Acaster Lane.

Born in 1894, he went to Bishopthorpe School then Priory Street School in York. An enthusiastic swimmer, he became secretary of Bishopthorpe Swimming Club, and also played cricket and football.

Ambrose Hudson is in the middle of the back row in this photo of 'The Bishops' football team. The Rev Edward Reginald Gibbs is back right

By 1911, he was working as a clerk at Leetham's Flour Mill in York. When war broke out in 1914, both he and his brother Benjamin volunteered for the army. By 1918, he was an Acting Sergeant with the Army Service Corps in Mesopotamia (now Iraq). Just two months before the end of the war, he fell ill with cholera, and died on September 15, 1918. He was 23. His remains now lie in the Baghdad (North Gate) War Cemetery.

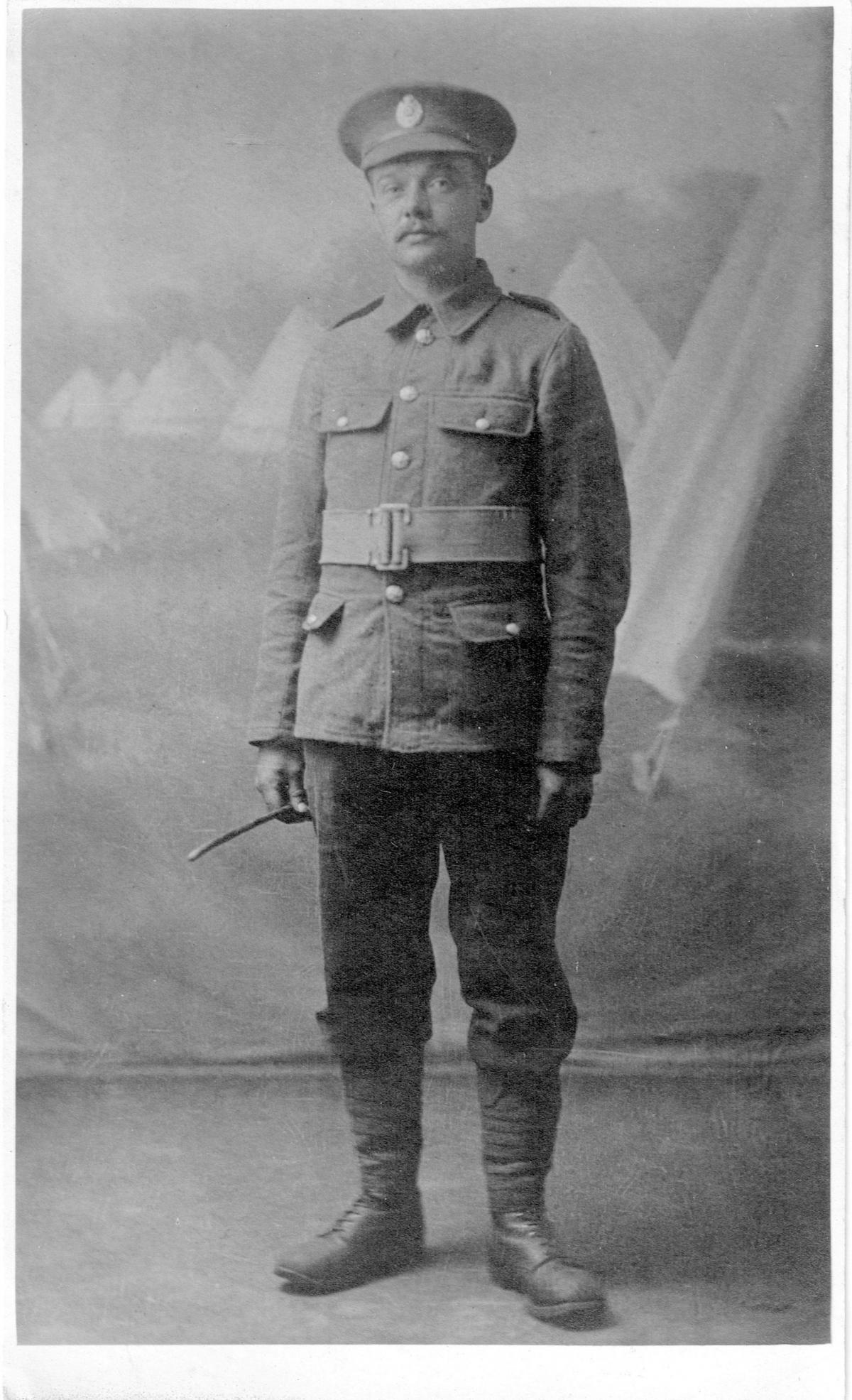

George Henry Simpson

George was born in Bishopthorpe in 1887, the son of John Simpson, owner of the Ebor Hotel. He went to school in Bishopthorpe, then York, and left in 1905 with a Certificate in Education.

In 1912, he joined York waterworks as a plumber. He decided to enlist with the army in February 1915, but had to wait for more than a year before he was called up to join the Royal Engineers. His unit, 208 Company sailed for France in August 1916. He spent Christmas in the trenches, and was slightly wounded early in 1917. Then, late on the evening of April 23, 1917, while 'on night work', a shell exploded near him, wounding him in the side of the chest.

Sapper George Henry Simpson in Royal Engineers' uniform. Photo: R Simpson/ The Lost Men of Bishopthorpe

At first it seemed the wound wasn't too serious: he asked an army chaplain to write to his mother Annie saying he was hurt but in good spirits. But the wound was obviously worse than had been thought. He died in a casualty clearing station at 8pm on April 25. His mother received a telegram informing her of his death several days later, on May 5. He was 29.

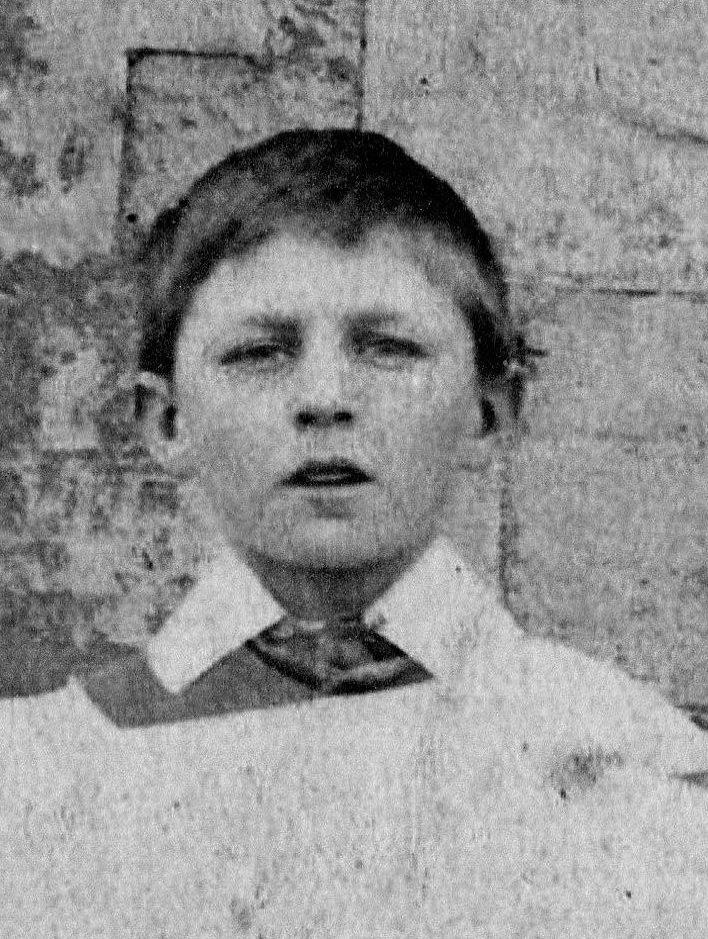

Daniel Fountain (whose name does not appear on the Bishopthorpe war memorial)

Daniel was born into a large Bishopthorpe family in January 1891. His father, also Daniel, was a gardener and mole catcher for Bishopthorpe Parish Council

Daniel joined the army in York on January 10, 1916, and by September that year had joined the York & Lancaster Regiment. He seems not to have suited army life. Records show he was punished several times for everything from dirty or missing equipment to being unshaven and late on parade.

Daniel Fountain as a choirboy at St Andrew's before the war

Private Fountain survived the war, but on returning to England in 1919 was sent to the Royal Victoria Hospital in Netley, where his illness was described as 'mental' - 'what we would no call post-traumatic stress disorder,' Ken Haywood writes.

Daniel was released from hospital to return to live with his mother. But his condition did not improve. In March 1923, he was admitted to High Royds psychiatric hospital near Otley - where he remained until he died of tuberculosis 23 years later, aged 55.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here