APRIL 29, 1942, is a date Alan Amour will never forget.

In the early hours, about 40 German bombers flew over the city of York, raining 84 tonnes of high explosives and incendiary bombs over the historic centre.

During the two-hour attack, 72 residents lost their lives, hundreds were injured, and some 9,500 homes were destroyed or damaged. The raid took its toll on the city's medieval Guildhall, as well as St Martin-le-Grand Church in Coney Street, and the Bar Convent on Nunnery Lane, where five nuns lost their lives.

The railway station was targeted too, with a Kings Cross to Edinburgh train at platform nine left a burnt-out shell.

Alan Amour was aged just 14 that fateful evening. By day, he was a telegram delivery boy, taking messages by bike across the city from the telegraph office just behind the main Post Office on Lendal.

By night, he helped his father George in his duties as a senior Air Raid Precaution (ARP) warden, which mostly involved making sure the blackout was observed and manning air raid shelters. In the event of a bombing raid, ARP wardens were also expected to report the extent of damage and assess the need for emergency help as well as give aid to people in the aftermath. There were 1.4 million ARP wardens in Britain, most of who were part-time volunteers who had full-time day jobs.

Alan and his father must have hoped that York would escape the might of the German Luftwaffe – but that all ended on April 29 when at 2.36am the first bombs fell on the city. The air raid sirens went off at 1.30am, Alan recalls. Although Alan's family lived in the Bell Farm area, which escaped the bombing, it was still a busy night.

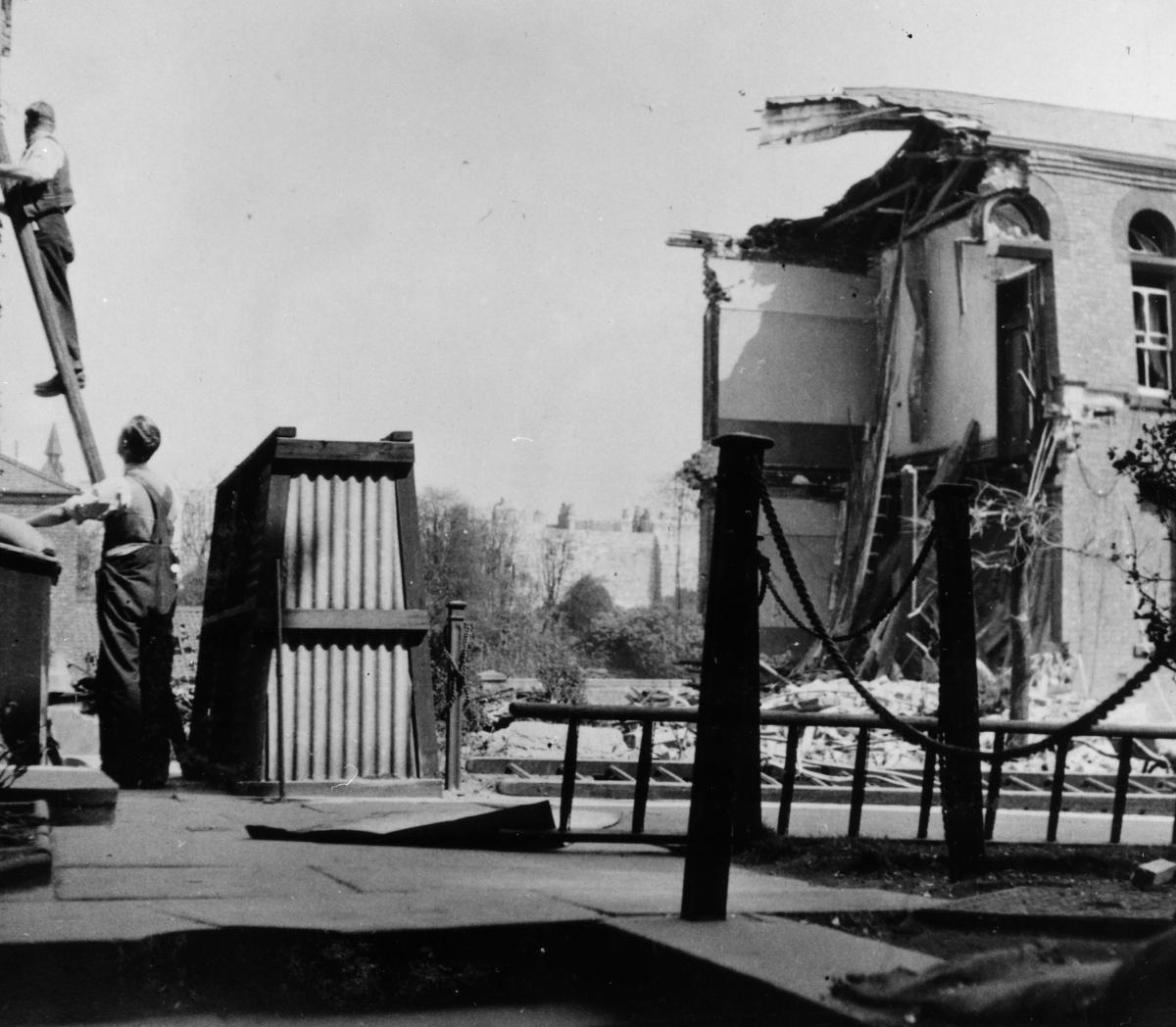

BLITZED: The morning after the raid shows bomb damage to the Bar Convent on Nunnery Lane

"The night of the raid, I worked as an ARP messenger, before going to work the next day. I helped my dad in sending messages on the state of the damage and what was being done.

"I came back home to check on my mother and brother. They were safe in the Anderson shelter in our garden."

Alan, now aged 89 and living in Haxby, recalls the scale of the bombing. "After dropping the main bombs, they sprayed the area with machine gins then used a device called the butterfly bomb, which had wings on it and if you got near it it would open out and explode."

Later, he learned the route the warplanes – Junker 88s and Heinkel 111s – had taken to reach their final destination. "It was reported that they followed the Humber to get on to the Ouse and used the river as a guide into the city. They used the landmark of the Minster to prepare themselves for the railway station. The area close to that was bombed too."

As daylight arrived, Alan was able to see the devastation at first hand as he arrived to pick up telegrams at the office on Lendal.

"The Guildhall was destroyed as well as the back of the Post Office," said Alan. The telegraph office was swamped with inquiries from people wanting to find out news about their loved ones. Normally, Alan would have two or three telegrams to deliver across the city. That morning, it was more like 30 or 40. It was going to be a busy day – Alan did not get home until 11pm.

His first call was to the Bar Convent at the junction of Nunnery Lane and Blossom Street. Ordinarily, he would have cycled over Lendal Bridge, but it was closed off because of the bombings. So he headed down Coney Street, but that too was only passable by foot, because of all the hose pipes and debris.

"I couldn't ride my bike until I got to Ousegate and Ouse Bridge. Micklegate didn't have a lot of damage, but when I got to Micklegate bar I could see the Bar Convent and how the main block on the Nunnery Lane side was totally destroyed."

Alan went into the building through its Blossom Street entrance. "I had telegrams to deliver, but there was no-one around. I thought, surely there can't be anyone alive here? I walked straight into the main hall and it was covered in rubble."

INSPECTION: Examining the damage to the bombed Guildhall

Next, he headed towards Leeman Road, via the railway station. "There was bomb damage to the train roof and to the lines as well as the train that was on platform nine. The train was totally burned out. The top half of the train was totally sheered off. You could see that it had been on fire."

Alan's next stop was to addresses on Leeman Road. The ones neighbouring the railway line had suffered the worst damage. "The houses facing Leeman Road on the left hand side were completely bombed. I tried to find some of the people I had telegrams for and a police officer told me some people were being looked after at St Barnabas School room, so I took the telegrams there."

It was a long, harrowing day, for the teenager. Many of the sites he visited were in fact graves. How did it affect him?

"You had a different attitude then," says Alan. "It was wartime and anything could happen. It was sad, of course. A lot of the people who died ended up in York Cemetery.

"But you don't forget something like that. You didn't dwell on that, but every time it is the 29th of April you remember what happened that night."

MORNING AFTER: Damage to St Martin-le-Grand Church, Coney Street

Background to the Baedeker raids

The April 29 1942 raid was just one of several bombings of British cathedral cities by the Germans during the Second World War.

Earlier, both Bath and Norwich had suffered aerial bombardment and York was on high alert that it could suffer the same fate.

In fact, just the day before, on Tuesday April 28 1942, the leader comment in the Yorkshire Evening Press expressed fears that York could be the latest in a long line of English cathedral cities to be targeted by the Luftwaffe.

The raids were dubbed "Baedeker" after the German tourist guides of that name. Apparently, Hitler had specifically ordered the attacks on unprotected British tourist cities – which had all been given three stars in the Baedeker guides – in retaliation for surprise RAF bombings on Lubek and Rostock in Germany.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel