A Lottery-funded project has documented the story of the community hospitals of the First World War. Ashley Barnard reports

THE role of the Voluntary Aid Detachment nurses throughout the First World War was vital, as swathes of injured men came back from the front with injuries never seen before due to the use of new artillery and technology in warfare.

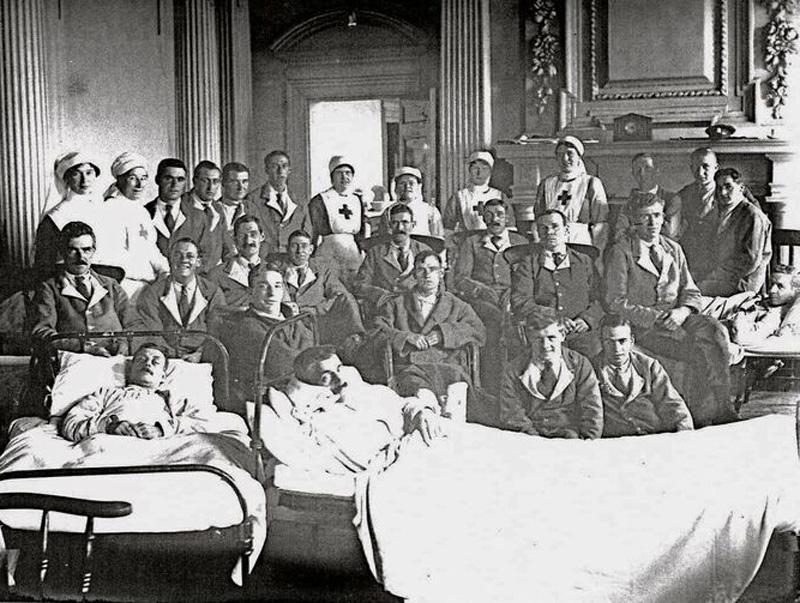

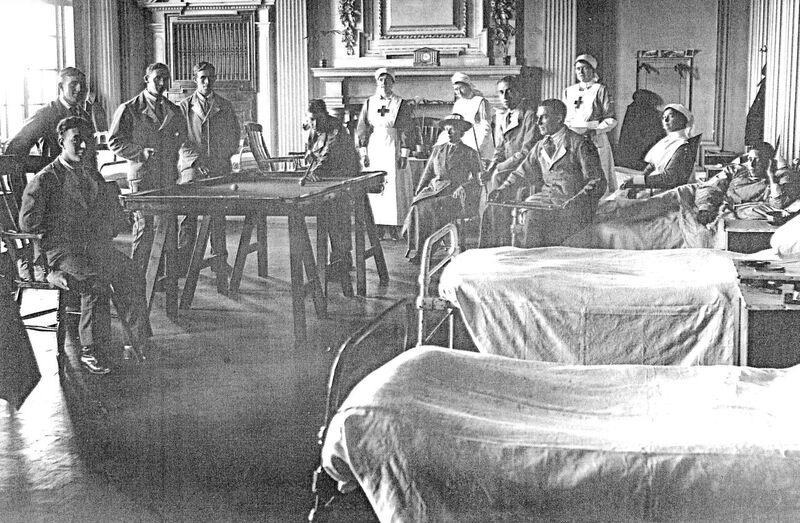

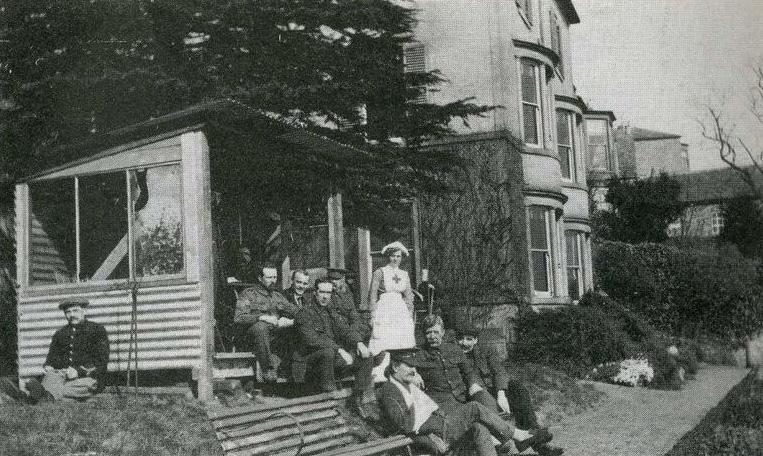

Countless village halls, community buildings and stately homes were converted into hospitals across the country in an attempt to meet the need for beds, mostly for rehabilitation once the men had received treatment or surgery, and Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurses were often at the forefront in the delivery of care.

In North Yorkshire, Red Cross hospitals, run by the VADs, opened quickly as communities and owners of large houses did their bit for the increasing number of casualties.

By 1916, the North Riding had 32 hospitals, ranging from small village halls such as East Rounton, to the grandeur of Northallerton’s County Hall.

That year, the call went out from Red Cross hospitals for more beds as demand grew due to the number of casualties coming from the Somme.

In Richmond, British Red Cross hospitals set up in Frenchgate House and Swale House, which had until recently been used as council offices, sent an urgent request for 20 more beds.

Between October 15, 1914, and January 10, 1919, a total of 1,628 patients passed through Northallerton’s County Hall doors and just two patients died there.

At the same time, Northallerton’s old grammar school was also used by the military and the school’s headmaster applied to use two of County Hall’s committee rooms as classrooms for a group of pupils who were preparing for their exams.

Despite County Hall being used by both the Red Cross and the school, the county council continued to conduct its business there.

Much research has been done on the county’s VAD hospitals by British Red Cross volunteers Anne Wall and Eileen Brereton, in a Heritage Lottery-funded project. They have recently published a second edition of their book, Home Comforts – the Role of Red Cross Auxiliary Hospitals in North Riding of Yorkshire 1914 to 1919.

Mrs Brereton said: “Our research started with Rounton Village Hall and took us all around the county.”

The pair have delved into the lives of nurses and soldiers who passed through the doors of the hospitals, and they found that by 1916 entire communities were involved in making sure everything was done to help the war effort as a whole, as well as their injured men.

Much of the food for soldiers was provided by local people who would bake, make jams and collect eggs, to ensure their soldiers could return to the front.

Since publishing the first edition of the book and doing talks to groups and schools, Mrs Wall and Mrs Brereton have received more stories and artefacts from members of the public who had relatives working at the hospitals.

Mrs Wall said: “We got an autograph book of Edie Pinkney, a VAD who cared for Belgian soldiers at the hospital in Bedale Hall.

“She was from Crakehall, near Bedale, and her relatives still living in the house were doing renovations and found an old priest hole. Inside the little room was Edie Pinkney’s autograph book, which was filled with little poems, pressed flowers and sometimes a few bars from a song.

“It was quite common for the nurses to keep books like this, as a kind of memory book, and many would continue to write to soldiers after they had gone back to the front.”

Eileen Brereton said the effort to help the war was taken seriously by all ages. “We were given a copy of a photograph of some boys from Ayresome School, in Middlesbrough, sitting among a huge pile of sandbags they and their classmates had made, waiting for a train at Middlesbrough station,” she said. “We heard a story about one little boy in Middlesbrough who was ill and off school making the sandbags while at home. They had to be made to exacting standards so they were suitable for the frontline.”

They found that VADs came from all walks of life, including ladies from some of the area’s stately homes.

Ursula Lascelles of Slingsby was a VAD nurse with her mother at Swinton Grange, Malton.

Mrs Brereton said: “She was a very young woman and she was initially refused because of her age. But she kept badgering the War Office until they agreed to let her.

“She was fascinating to us because she kept scrapbooks of her life, with pictures, letters and reports of her time as a VAD and after.”

Lady D’Abernon, sister of Lord Feversham of Duncombe Park – which was also a Red Cross hospital – trained as an anaesthetist in Europe, and was proud that she had not lost a single one of her 1,137 patients.

At Duncombe Park, the hospital kept a collection from 1916, including a list of all the men and what was wrong with them – most entries were for gunshot wounds and trench foot.

But Mrs Brereton said the most seriously injured soldiers would have been treated in the South so they would not have to travel as far. She said: “In North Yorkshire, the wounds would not have been so severe or life threatening.”

Anne Wall and Eileen Brereton are continuing to give talks on the book, and their exhibition will be on display at York’s Castle Museum in 2017. For a copy of the book, email anne@wallfamily.demon.co.uk.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here