A series of photos of the York Carriageworks in The Press a couple of weeks ago prompted former coachbuilder Gordon Smith to come forward.

Gordon, now 70, worked at the carriageworks for 35 years, from leaving school at the age of 15 up to the day the works closed, when he was 50.

He's still bitter about the way it all ended - especially the way employees who had given years of their life to the company were at the end denied the rail passes they regarded as their right by the ABB management.

And there is, of course, that whole issue of asbestos.

But for most of his time there, the carriageworks was a great place to work, Gordon says - especially the earlier years under British Rail.

Gordon grew up in Horsman Avenue, just off Cemetery Road, and went to Fishergate primary school and then Danesmead secondary modern.

He left school at 15 and joined York Carriageworks in August 1961, working first in the offices and then, after five months, becoming an apprentice coachbuilder.

The apprenticeship lasted six years - a long time, but worth it for what seemed to be the promise of a decent job for life.

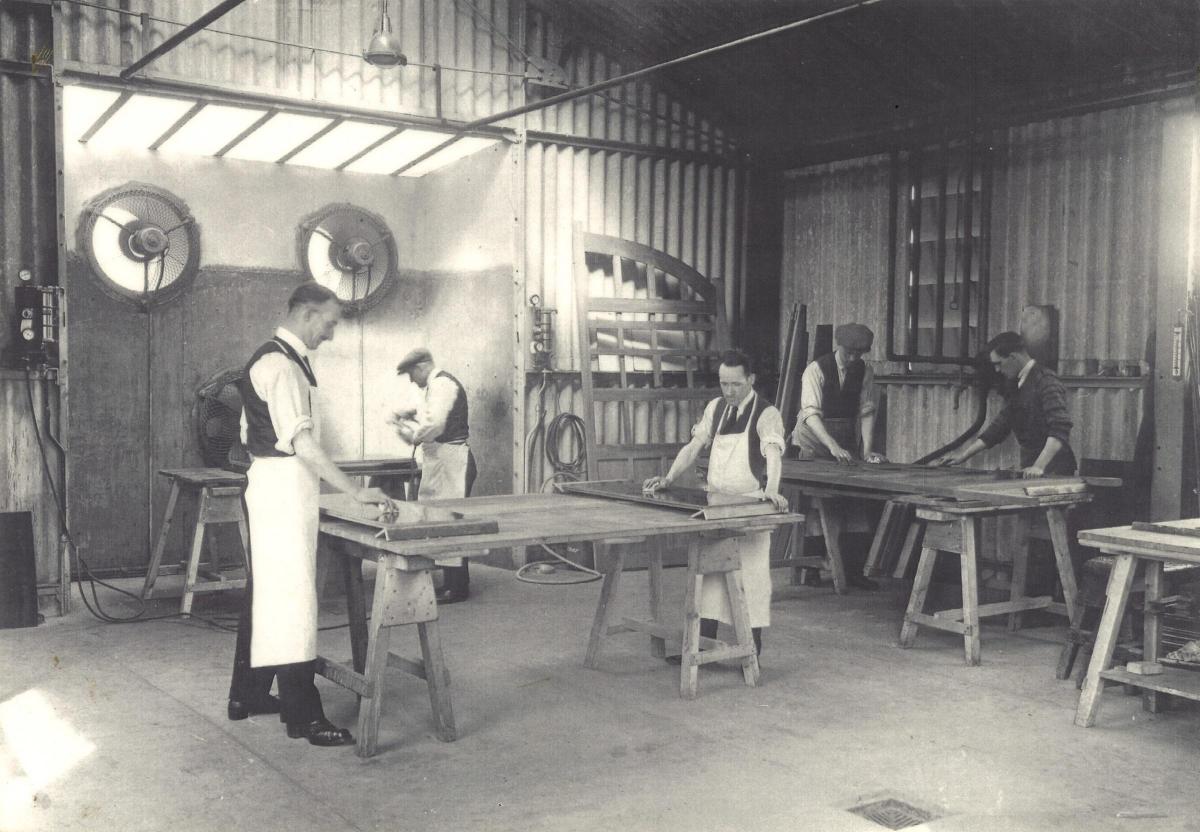

The steel metalworkers' shop

As a coachbuilder, Gordon worked in a huge coachbuilding shop where, at any one time, there could be three lines of a dozen or so coaches being built.

It wasn't exactly a production line, he says, but coaches were assembled bit by bit: the floors, the body sides, and so on.

It could be deafening in there, he admits. "When you were putting the body sides on, you had to bang them in, and the welders would be knocking the flux off the weld. It was pretty loud - and there were no ear defenders."

There was little protection against asbestos, either, he says.

"I started work in the building shop in January 1963. One of my first jobs was working on buffet cars. My main job was heater covers and radiators in the vestibule end.

The lifting shop, October 25, 1963

"At the base of the radiators where the pipe went through the floor, there was a gap. As the apprentice, one of my jobs was to acquire a handful of dry asbestos, mix it with woodlock glue and fill in the space around the base of the pipe.

"Most of the spraying of blue asbestos was done at the top of the paint shop. The only protection for workers in the area (which included myself) was a sacking curtain."

In 1965 Gordon moved for a few months to the 'aircraft shop' - so called because it was where, during the war, aircraft parts had been made - and then, at the end of 1965, to the repair shop. "It was mainly repairing old coaches, but we did smash jobs too," he says.

For ten years, Gordon was also a member of the Territorial Army's Royal Army Medical Corps. That gave him medical qualifications that also enabled him to do some work in the carriagworks' medical room.

During his 35 years there, Gordon became familiar with just about every aspect of what was going on in the works. There was virtually a different 'shop' for each job, Gordon said.

The sewing machine room, February 1968

In the 'sewing room' for example, there were upholsterers and trimmers upholstering the carriage seats. "They were all women when I first joined, but when sex discrimination legislation came in, there was one labourer who was quite good at sewing. He joined in there - and he was good!" In the wheel shop, meanwhile, metal 'tyres' - essentially the flanged metal wheel rims that stop coaches sliding of the track - were heated in pits using gas blowers. The wheels were then dropped in, the rims allowed to cool - and as they did so, they gripped the wheels tight.

"It was a wonderful place to work," Gordon says.

Towards the end, however, it became clear the works were going to close. His main anger is reserved for the way staff were denied their rail passes.

Many older employees, who'd been at the works for years, were looking forward to retirement and using their passes to travel the country, he says.

The coachbuilding team on a final shift. Gordon Smith is centre, eighth from left

He himself landed on his feet after being laid off at the age of 50.

He worked for marks & Spencer for a while, then got a job as a civic support officer in the Lord mayor's Office. "I used to drive the Lord Mayor, and carry the sword and mace."

From there, he went on to become driver to the archbishop of York, Dr David Hope - and ultimately became 'palace warden' at Bishopthorpe Palace under two Archbishops, Dr Hope and John Sentamu. It was a job he did until he retired - and with the job came a four-bed flat in the palace itself.

Others of his ex-colleagues weren't so lucky, however.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel