IT is one of the great treasures of medieval England. But what do we know about the people who made York Minster's Great East Window?

In some ways not very much.

We know that John Thornton, the master glass-painter who designed the window and sketched out designs or 'cartoons' for every one of the more than 300 panels, originally came from Coventry. He bought a house in Stonegate, York, and was still living in the city in 1433, almost 30 years after he arrived to begin work on the window. But we don't know what he looked like, what kind of person he was - or even whether he married and had a family.

We know even less about the other glaziers and glass painters who would have worked with him during the three years it took to make the window: not their names; not even how many of them there were.

In other ways, however, the great window itself - Britain's biggest expanse of medieval stained glass - holds tantalising clues about the people who made it more than 600 years ago.

Take the faces that feature so prominently in much of the glasswork - the face of God, of angels, of characters from Genesis, of Christ sitting in judgement. In one sense they are 'types', admits Sarah Bown, the director of the York Glaziers Trust, which is nearing the end of a two-part, six-year project to restore the window. The men all tend to have bulbous noses, for example.

Sarah Brown, director of York Glaziers Trust

But they are much more than that. There is some astonishing detail - in the hair, the beards, the lines on faces, the expression in the eyes - that make these far more than just caricatures.

Take the face of Adam, as he bites into the apple in a scene from Genesis. "He looks suitably downcast and depressed, as if he knows it's all downhill from here," says Sarah. And so he does. Adam's face is lined and haggard, his eyes haunted, as if by knowledge of what he is about to do, and about to lose. It is art of the highest order: a real human face caught in a moment of appalled inward reflection.

Haunted and haggard: detail showing Adam biting into the apple

We don't, sadly, know whether this face was painted by Thornton himself. It is likely he would personally have been responsible for painting some of the more important figures and scenes in the window, says Sarah: we just don't know which.

But whoever painted Adam, to get this degree of sensitivity and individuality, they must, surely, have drawn upon what was around them. So are the faces we see in this window the faces of Thornton himself, or of his colleagues, family and friends, painted from life?

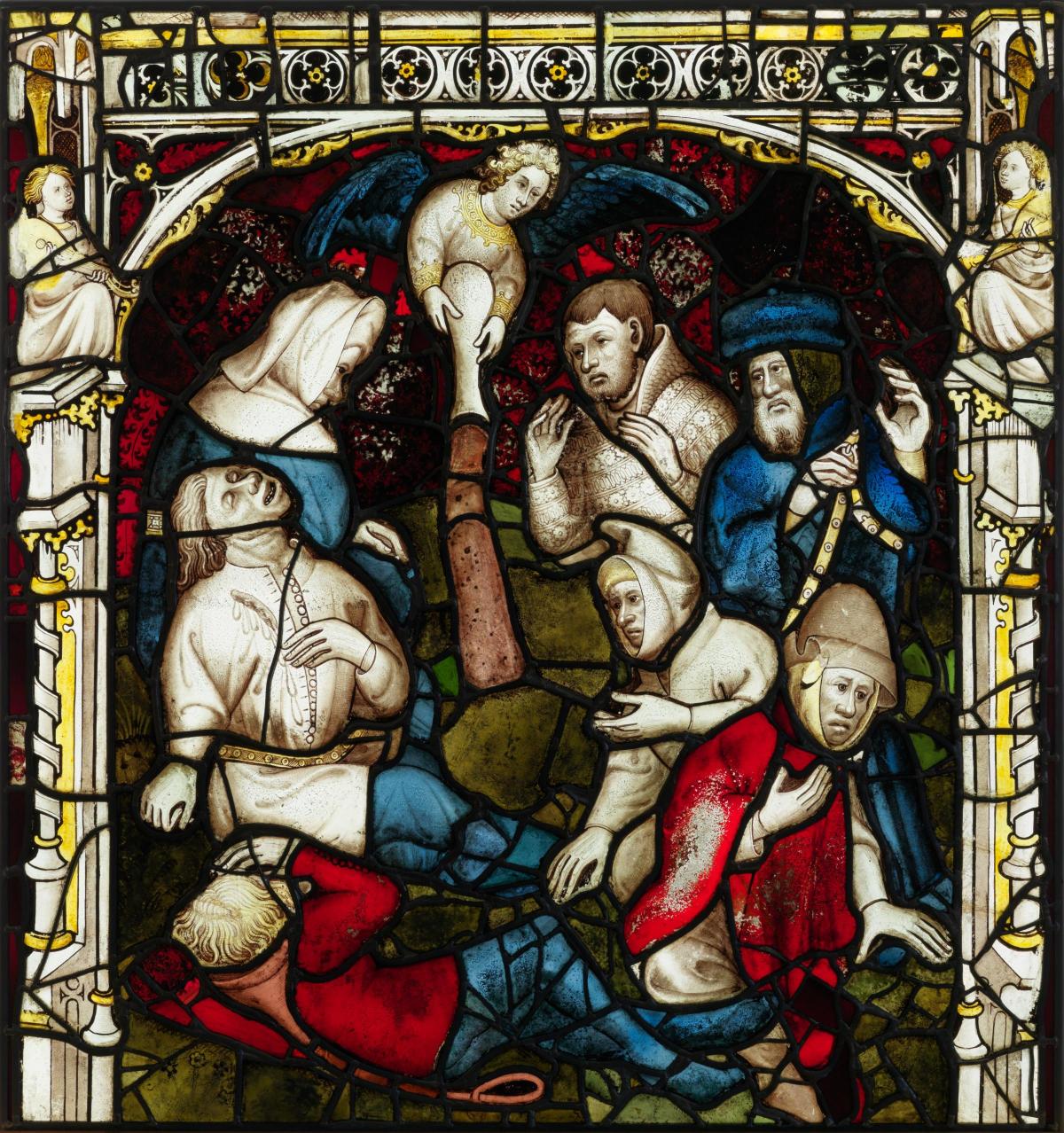

Faces from a scene depicting the 'pouring of the fifth vial' (Revelation 16:10-11). Would these have been based on people John Thornton knew? Perhaps not, says Sarah Brown

Probably not, Sarah says. Despite their vigour and sensitivity, the faces are too much of a type for that. "So I don't think we are looking straight into the eyes of friends who lived next door to Thornton. But in a general way we are certainly looking at medieval people."

That is certainly true of the clothes of the figures depicted. When Thornton and his colleagues painted the biblical scenes, they didn't try to imagine what characters from the Old Testament would have looked like, or what they would have worn.

The people who fill the Great East Window are medieval Englishmen and women, in medieval English clothing. They're 15th century townsfolk: wealthy merchants in richly-coloured robes; peasants and working men in rough-spun brown cloth; others in coloured leggings.

The 'pouring of the fifth vial' from Revelation 16:10-11: the figures are dressed as medieval Englishmen

Even the hairstyles are contemporary to Thornton's time, says Sarah. The serpent that appears between Adam and Eve in the scene where Adam is about to bite into the apple has the face of a woman: and her hair is carefully coiffed in the style of a fashionable woman of the day.

The face of the serpent: her hair dressed in fashionable 15th century style

To medieval people looking at Thornton's great window, therefore, the whole thing would have seemed very modern and contemporary, the people pictured just like themselves. To us, however, it offers a wonderful window into the past: a real glimpse of what life was like in the early 1400s.

The window also contains other tantalising traces of the people who made it and the times they lived in.

The way Thornton and his glass-painters worked was to build up layers of paint to create the figures and scenes. The painted panels were then put in a kiln to be fired. Sometimes, as they were doing this, the glaziers would leave a finger or thumbprint on the glass, which would then be fixed by the firing process. These prints are almost always on the edges or at the periphery of scenes - a finger- or thumbprint on a face would presumably have required the scene to be painted again, says Sarah. But looking at these prints, you feel as if you're very close to the glaziers who made this window 600 years ago.

Detail showing thumbprint left by one of the medieval glass-painters who made the Great East Window

Other panels contain traces of linen fibre that have been fired into the paint.

They're only visible when you look very closely. At first, when he spotted them, senior conservator Nick Teed was annoyed, admits Sarah, thinking they had been left by colleagues cleaning and restoring the window. "He thought they were little bits of cotton wool from the cleaning." But closer investigation revealed they were actually 600 years old - fibres from the clothing of the glass painters who originally painted the window. "They must have been deposited before the glass was fired," Sarah says.

A face in the Great East Window, with linen fibres from a medieval glazier's clothes caught in the paint

The window is also covered in graffiti - although you'd never know it from a distance. Most of this is the work of restorers who worked on the window in the 1790s and again from 1824-1826. Some examples are simple names and dates scratched into the glass: others seem to be instructions to remind restorers which piece of glass goes where.

Perhaps the most significant - though it would never be seen by anyone looking up at the window from far below - is that etched into the panel that sits right at the very top of the window.

The panel shows God sitting in his majesty, holding a book stating “Ego sum alpha et omega” - I am the alpha and the omega, the beginning and end of all things. It sums up the theme of the whole window, which tells the story of creation from its beginning to its end at the Day of Judgement.

But right in the centre of God's forehead, an unknown restorer in the 1820s inscribed the following two words: 'Top Front'.

Well, it wouldn't have done for God's face to be replaced in the wrong part of the window, would it?

The face of God, with 'Top Front' scratched on his forehead by a 19th century restorer

- All images supplied by York Glaziers' Trust, apart from photograph of Sarah Brown by Frank Dwyer.

The story told by the Great East Window

The Great East Window is an Apocalypse window, which tells the story of the beginning and end of all things, from the Creation to the Day of Judgement.

At the top is God the Father holding that book with the words “I am the alpha and omega.”

Almost 150 tracery panels contain images of angels, saints and martyrs.

Three rows of panels then depict episodes from the creation of the world as described in the book of Genesis - including that scene of Adam biting into the apple as Eve and the serpent look on.

Blow that are scenes that presage the end of the world and the second coming of Christ as told in the Bible's Book of Revelation - known in the Middle Ages as the Apocalypse.

Panel depicting Bishop Skirlaw, who paid for the window

The bottom nine panels illustrate historical and legendary figures from York's history, including kings and saints. Chief among these is the figure of the Bishop of Durham, Walter Skirlaw, who paid for the window. It was quite an outlay: John Thornton alone was paid the princely sum of £56 for his work, equivalent to hundreds of thousands of pounds in today's money: the full cost of the window would have been much greater, Sarah says.

Restoration of the window

Work started on Phase 1 of the restoration of the glass of the Great East Window in 2011, as part of the wider Heritage Lottery-funded York Minster Revealed project. All the glass was carefully removed, and has since been cleaned and repaired before being re-leaded, using a technique that greatly reduces the amount of lead needed so that the story told by each panel becomes clearer.

Phase 1 is now almost complete. All the Apocalypse panels, the panel showing God as the beginning and the end, and the majority of the tracery panels, have already been restored and cleaned, and replaced in the Great East Window. Protective glass has also been installed on the window's outer face.

The external scaffolding is now coming down, and should be gone by Christmas, and the internal scaffolding is also being removed. As the scaffolding continues to come down, you should be able to see more and more of the window.

The remaining panels - those showing the scenes from Genesis, for example, plus some of the tracery panels - are still being cleaned and restored by glaziers in Phase II of the project.

Work on these will not be completed before the end of 2017, when a lightweight internal scaffolding will be used to put them back in place.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel