YORK in June and July 1914 was a city unimpressed by the looming prospect of war.

The Yorkshire Herald, the city's main morning newspaper, had covered the murder of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28 in some detail. But the people of York didn't seem particularly interested, writes York-based historian David Rubinstein in his recently published York In War And Peace.

In late June, a column in the Herald's sister paper, the Yorkshire Evening Press, mused that the normal man cared more about the activities of the household cat than about events abroad. "So long as his own domestic tranquility was not disturbed he was unconcerned," David writes.

By late July, it was clear that storm clouds were gathering. "War Confronts Europe" ran a headline in The Press that day.

York's Liberal establishment were very agitated – and very opposed to the prospects of war. Cllr JB Morrell said at a meeting at the end of July that he knew of "no single war in history when there had been less reason why they should embark upon war... than the one... being urged at the present time."

The city's Liberal MP, the Quaker Arnold Rowntree – nephew of Joseph – agreed. It was the "absolute, paramount duty of everyone to work incessantly to prevent the people of England being run in to any war," he said.

For most people in York, however, life went on pretty much as before, right up until war was declared.

The columns of the York newspapers in those final days of peace were full of the things that mattered to the city's people. The late Dr Alf Peacock, in his history of the times – York In The Great War – describes adverts for a clothing sale at Isaac Walton and Company; regular letters of complaint about new-fangled motor cars; and a host of adverts for patent medicines: Blanchard's Pills For Ladies, Lilian Pinum's Cure All, and even free tooth extraction, provided you paid for a false tooth afterwards.

It was all a bit like the quack medicines you'd expect to be offered by travelling salesmen in the Old West, Dr Peacock wrote.

And then there were the suffragettes.

Dr Peacock reprinted a letter published in The Press on August 5, the very day that York's newspaper announced 'War Declared On Germany'. It was from one Edith Milner, of Heworth Moor House and it was bubbling with outrage. "Will no one protest in the name of our common womanhood against the conduct of our Suffragettes?" she asked. "That they have become a deadly peril to the national life has long been apparent..."

The citizens of York may not really have believed that war would come – but, just in case, those who could afford it decided to hoard supplies.

In Dr Peacock's words, they "engaged in an exercise of denuding the shops of everything edible they could lay their hands on."

When war was declared on August 4, it was greeted in York with 'great excitement'. The Yorkshire Herald reported that a large crowd gathered outside its offices in Coney Street, writes David Rubinstein. When the declaration of war was announced there were "loud and prolonged cheers... and the National Anthem was heartily sung."

Young men rushed to volunteer for the army – although many of them, the Yorkshire Herald noted, came from outside York rather than from the city itself – and suddenly York's streets were filled with military personnel. Officers were "hurrying hither and thither in motor cars, taxis, on motor-cycles, cycles, in cabs, and in every kind of vehicle available," the Yorkshire Herald reported on August 6.

Most, in those heady first days, thought the war would be over by Christmas. Preparations were even made to accommodate German prisoners of war. "The (Evening) Press claimed ominously that the castle could accommodate 40,000 persons," David Rubinstein wrote.

As we know now, the Great War was to last a great deal longer than that. By the time it was over, four years later, millions had died – including as many as 2,000 young men from York – and the world had changed for ever.

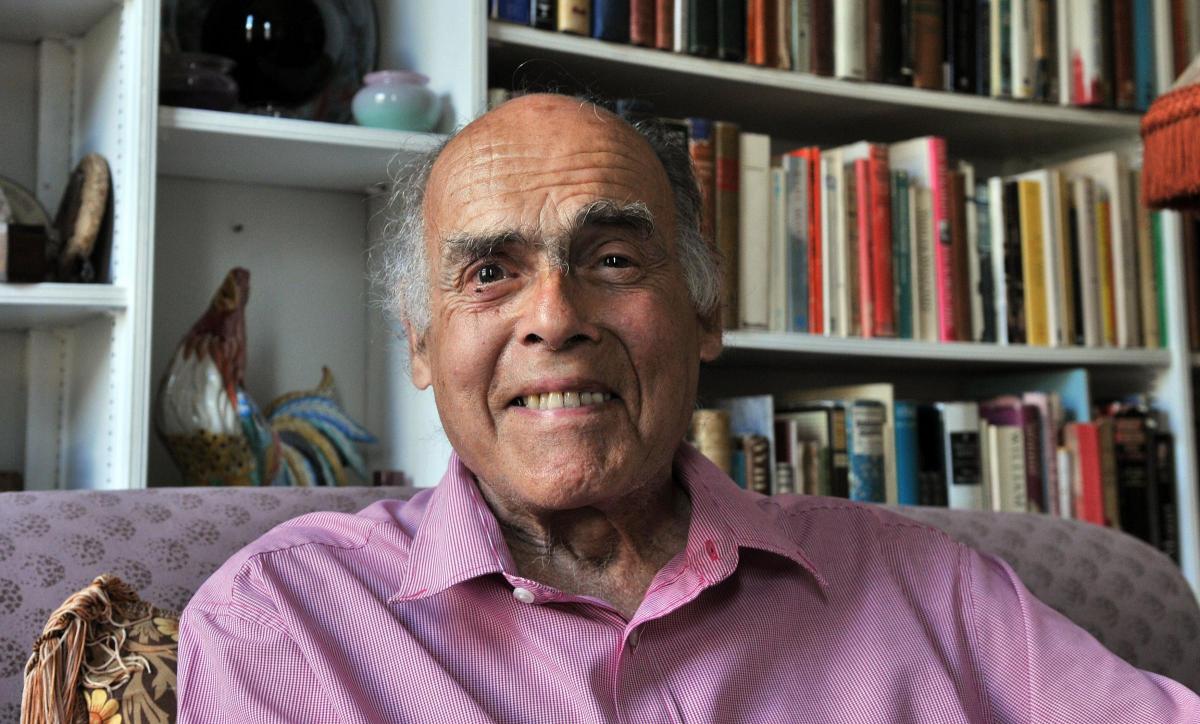

In many ways, the war was to prove a real catalyst for change, admits Dr Rubinstein, a retired senior lecturer in social history who lives in York.

"York changed in the same way as the country changed," he says. "It became a more modern place, less Victorian."

Before the war, it had been a city of extremes of wealth and poverty: one in which the ordinary working man knew his place, and by and large did what he was told.

Afterwards, English society was never the same again. The war accelerated the pace of change - including the granting of the vote to women.

"But it came at a terrible, terrible cost," Dr Rubinstein says.

York In War And Peace is published by Quacks Books, priced £10

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here