BETWEEN this month and March next year, the National Railway Museum is lifting the lid on the much misunderstood hobby of trainspotting.

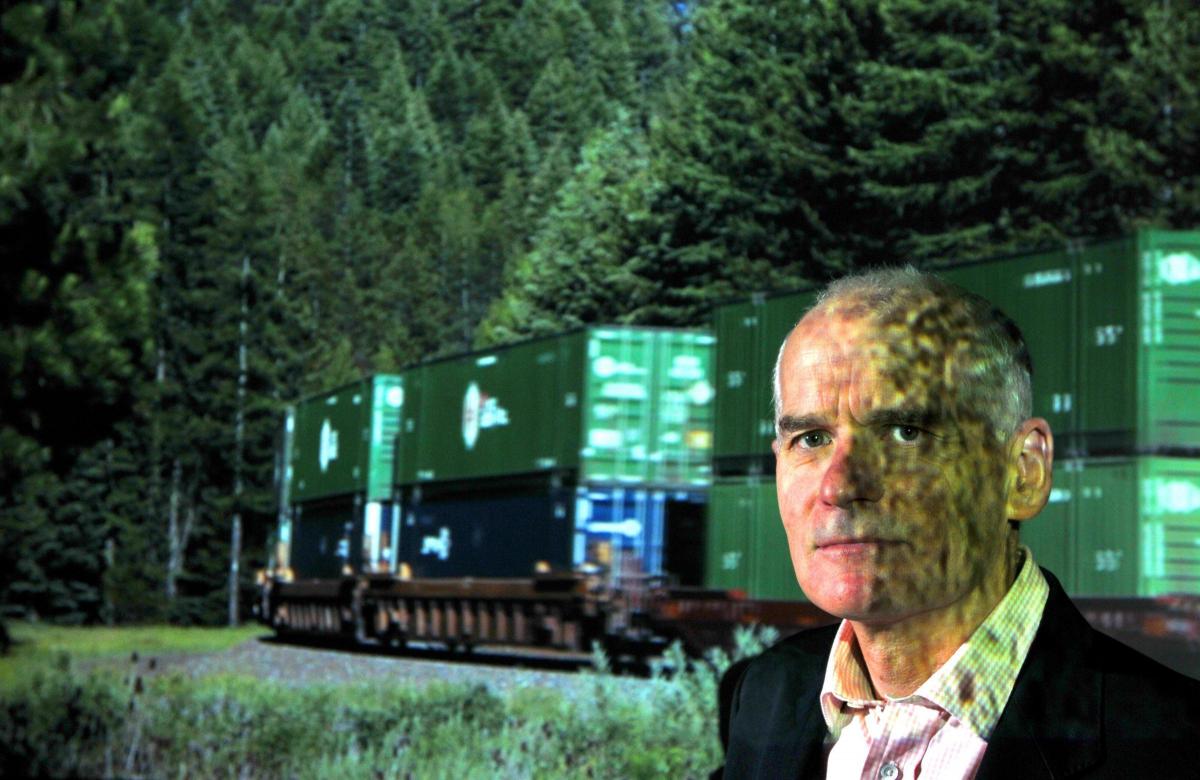

No work will do that better than Parallel Tracks, an art installation in film by Andrew Cross, a dapper English artist whose diverse practice is concerned with memory and place formed out of personal experience.

As the title suggests, his new commission Parallel Tracks makes you look at trainspotting differently – the very essence of what art should do – as he presents the experience and method of trainspotting in a new and contemporary way, rather than through the rose-tinted lens of nostalgia. "My work is to do with stripping away everything from the expectation of what a train photograph should be," he says.

Why was Andrew selected from a field of over 120 artists? "Because I was better than them," he says with an exclamation mark in his voice, before elucidating his passion for the project. "I had a history of being a spotter, as well as being an artist who has made artworks internationally for public demonstration [such as The Solo, his 2010 collaboration with rock drummer Carl Palmer, and his 2004 Film & Video Umbrella commission, An English Journey].

"And in terms of that, I was damned if someone else would get this commission, because I've had an passionate interest in trains since the age of ten, not because it is artistically clever to do train pieces.

"My dad was beside himself with delight when I told him I'd got the commission. All those days miserable, wet days of being collected in the rain at railway stations had paid off; all those days of my mum making me egg sandwiches."

What first drew Andrew to trains? "I don't know! But I did grow up on the Salisbury Plains, where agricultural and military machines articulated the landscape, and that's what happens when I go to America, where trains articulate the landscapes so strikingly."

In Parallel Tracks, trains articulate not only American plains and cities, but also the countryside of Oxfordshire and Wiltshire and the mountainsides of Switzerland in a series of films that run to one hour and 40 minutes. So hypnotic do they become, with their combination of anticipation, train arrival, motion, noise, size, beauty, landscape and interaction, that while you could dip in and out, coming back every so often while train-spotting elsewhere in the museum, equally you could watch all the way through.

What strikes you is both the artist's eye in the very formal composition of his films, albeit that serendipity played its part when trains crossed as he filmed, but also the boyish enthusiasm for trains that Andrew has never lost. "Nick Hornby talks about this really well at the beginning of Fever Pitch, when he writes about why do boys become obsessed with a particular football team at that age? There is something about that age. Some boys get taken to football; I didn't; I got taken to Reading railway station, and I realised the potential in trains. The potential to travel," he says. "I must have travelled to virtually every city between the ages of 11 and 13, and my memories were always of travel rather than of trains."

On August 21 1976, Andrew discovered the "holy trinity of sex and drugs and rock'n'roll". "I went to see The Rolling Stones at Knebworth, but that's when I also experienced Lynyrd Skynyrd, and myth has it that they blew the Stones away, and to some extent they did.

"That was when my love of American rock was born, and through that love, I went to America. Then, in 1994, James Welling, professor of photography at UCLA [University of California], took me on a weekend's train-watching to Allentown, Pennsylvania, when until then I'd barely ventured out of New York and LA, and at that moment, I felt I was ten again.

"I knew I would spend the next ten years exploring America through train trips, going to places I would otherwise never go to – and part of that would be playing American rock music as I was doing it."

Music does not feature in his film installations: well, not unless you find musicality in the rhythm of a train, which you most certainly will. "What I'm offering in my installation is everything that's not offered in a photograph. I offer the atmosphere, the sounds, and it becomes Zen-like.

When I'm doing the filming, I'm in the zone; I can stand for four and a half hours waiting for something to happen, and then a train will pass through a city street, for eight to ten minutes of creaking and groaning metal sounds, as it becomes a steel wall. People can't do anything but wait for those ten minutes."

In conversation, you can hear Andrew's revived thrill in transportation, in where trains take him, in the joy of anticipation. "This commission has taken me back to my roots and I'm really grateful for that. I want people to respect the hobby of trainspotting and hopefully my installation and the NRM's Trainspotting season will make people re-evaluate the hobby," he says.

"The great thing about it, and one of the reasons there is a cultural problem with the hobby, is that on the one hand it's collective, but on the other it's also individual because there are no set rules.

"When people say they 'don't get' trainspotting, that's the whole point. There's nothing to get. I approach it in my own way, just as everyone else does."

Andrew Cross's art installation Parallel Lines forms part of the Trainspotting season at the National Railway Museum, York, until March 1 2015. For more information, visit www.nrm.org.uk/trainspotting

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here