PIERRE de Coubertin founded the modern Olympic Games with the creed, “The most important thing is not winning but taking part”.

This sentiment that would chime with German travelling artist and designer Sybille Neumeyer, who has won the 2014 Aesthetica Art Prize in York with her installation Song For The Last Queen but has more altruistic reasons for creating her lament to the endangerment of bees.

“I didn’t do this piece to win a prize,” said Sybille at the exhibition launch and prize ceremony at York St Mary’s, Castlegate last Thursday.

“I was excited to be chosen as one of the eight finalists and I feel honoured that my work is on the exhibition poster and guide because that means it’s reaching more people. It’s important not only for an artist to have a message but to have ways of reaching people with that message too.”

Song For The Last Queen is being exhibited in Britain for the first time after shows in Stuttgart and Sankt Andreasberg, where the exhibition focused on the relationship between humans and nature. This relationship is at the heart of her work too, for which Sybille worked with beekeepers in the United States, Japan and Germany to research the problem of dying bee colonies when they play such a vital role in maintaining the eco system.

“I knew bees were an endangered species but I came to the idea of doing this installation by a different route, when I was researching natural weather indicator systems, including climate and weather changes, in the Catskill Mountains in Upstate New York,” says Sybille. “So I started getting more interested in bees because they react to thunderstorms and rain.”

She had the chance to observe the bees at close quarters in the hive and even see bears attacking beehives. “It all brought me to the global topic of the bee-colony collapse disorder, and then I collected collected honeycomb, wax and dead bees from a collapsed beehive, examining each, both as evidence and as a significant and extraordinary material,” says Sybille, who also became fascinated by honey having different colours from the different pollens.

Once she returned to Germany, Sybille conducted several tests on the preservative qualities of honey. “I wondered if bees could be preserved in their own produce,” she says. “Though the real question is, shouldn’t we be trying to preserve bees before they die out, not when they’re preserved in an art piece?”

Her installation takes the form of a “muted preparation” of a perished bee colony. In layman’s terms, it is a back-lit series of sealed tubes – phials, if you prefer – that glow like liquid gold on account of the honey inside them. They have the movement of a piece of sheet music, hence the “Song” of the title, but on closer inspection, it turns out that each tube contains a dead bee.

“That’s why I decided to make it shiny, attractive and aesthetically pleasing because it looks so beautiful and intriguing and enticing, but then, close up, you see the dead bees, so the piece gives you the chance to have an emotional response to it. It’s a sad topic, in a beautiful way of presenting it,” says Sybille.

Each phial contains the amount of honey that the average bee can produce in a typical life expectancy of five or six weeks, a further reminder of their vital role.

“Although the honey is preserving the bees, I didn’t put anything else in there, so the honey will eventually crystallise, which is another point of the piece. It’s ephemeral. It won’t last. There’s a moment of transformation or transition, which is where we always are in the world. In that moment, we think about where we are and where are we going?”

The Aesthetica Art Prize is run jointly by Aesthetica, the international arts and culture magazine edited and published in York, and York Museums Trust, and it awards not only the main prize but also a student prize. This year, that prize has gone to Londoner Harriet Lewars, newly graduated from London Metropolitan University – “London’s third worst university,” as she endearingly calls it – with a first in fine art.

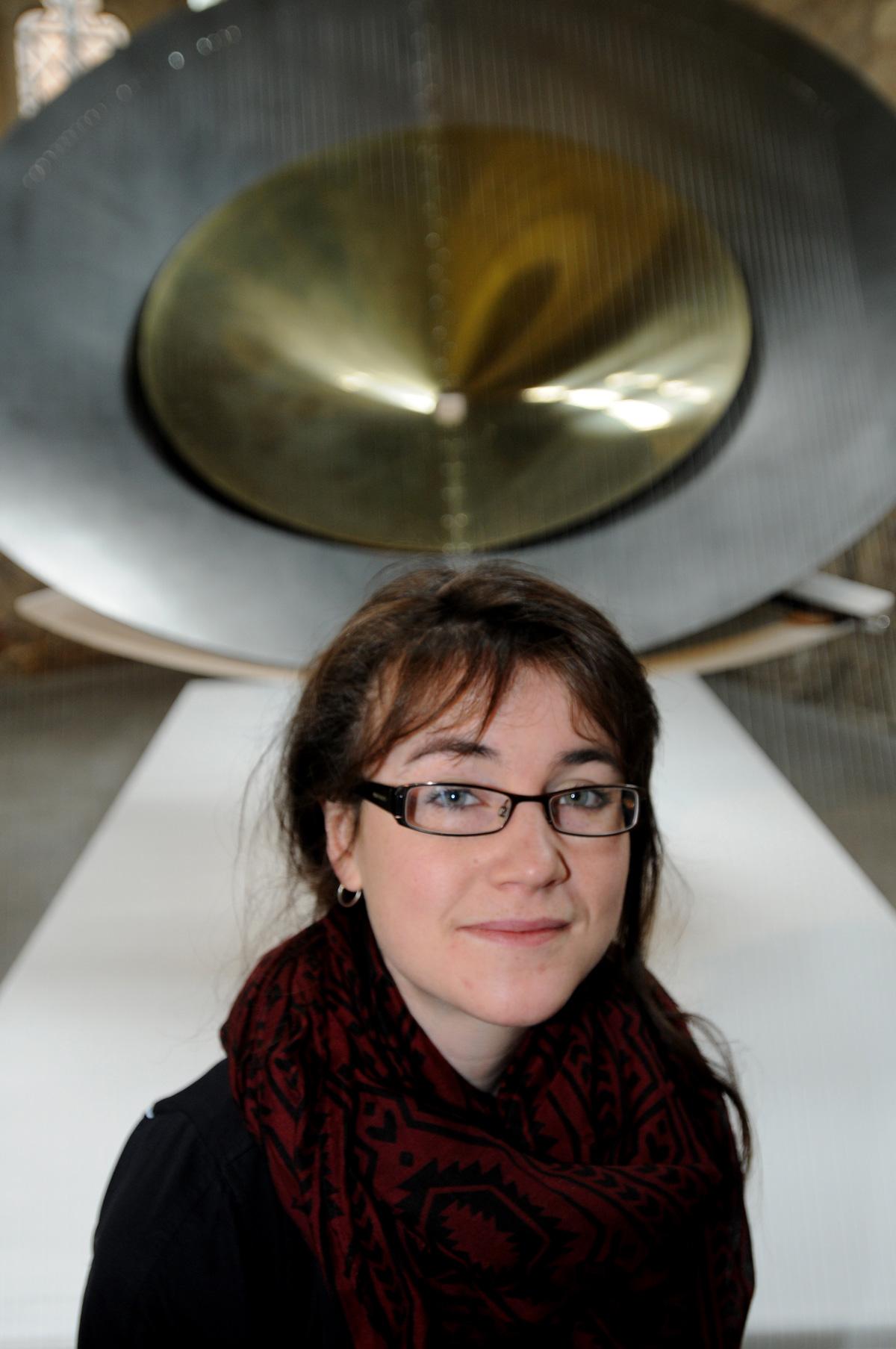

She describes her aural 3D sculpture, Frustrum Super Planum Cum Filia Lyrae, as being part of a project at the interface between art and music. “The title means it’s a truncated cone with some strings on,” she says, debunking any accusations of pretentiousness.

Harriet apparently had requested ten days to assemble the sculpture that she had first put together as part of her degree show in her shed. She settled for a week in the end, and it is indeed a complex piece built in sheet metal and mounted above a horizontal plane, with the metal then acting as a soundboard from which many strings are stretched (hence the time-consuming assembly).

Ah, but can you play it? “In theory, yes, you can,” says Harriet, who plays violin “cheerfully” in quartets and assorted groups in people’s homes, but not in public. “You could pluck the Frustrum’s strings or bow them or experiment with them percussively.

“It’s magical when the strings are tuned perfectly at the right playing tension; it makes a loud echoing sound somewhere between a guitar and a cello with big harmonics. What makes it interesting is that it falls between categories because I made it for a Fine Art degree but now I can look at it musically, or even better, someone else can, once I’ve worked out a notation form for it.”

The Aesthetica Art Prize exhibition, A Presentation of Shortlisted Works from Eight Contemporary Artists, runs at York St Mary’s, Castlegate, York, until June 22.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here