Homelessness is on the increase in austerity Britain. STEPHEN LEWIS visited Arc Light to find out about the lives of people living there

THE poem has the angry energy of rap. In fierce, vivid language, it captures something of the loneliness and defiance of life on the streets.

“Being recluse and all alone, in a bustling city I call home

“Faces come and faces go, like the tide, the ebb and flow.

“Picked on, spat at, jeered and stabbed,

“Relentless torture for this homeless lad.

“Unseen suffering, inner scars unhealed,

“But my pride and sanity I’ll never yield.”

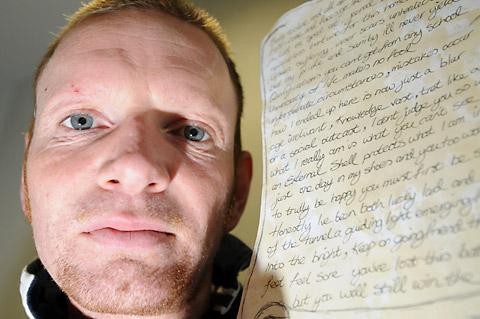

The man who wrote this poem is, as you might guess, homeless. In many ways, Graham Falconer’s life has been what you would expect.

He has been homeless off and on for 17 years. Much of that time he has spent in and out of hostels, ‘sofa surfing’ on friends’ floors and sofas, or sleeping rough on the streets.

There have been drink, and drugs. And, as the poem suggests, Graham has been stabbed. That was in 2000. He was asleep in a house in Melbourne Street, York, when he was attacked by a man wielding a knife. He was stabbed in the stomach and right buttock and needed surgery to stop heavy bleeding from an artery. “The lad that did it had a bad trip,” he says. He has the scarring to show for it and still suffers flashbacks.

In many ways, however, Graham’s life has been very different from what you might expect.

There is his army background, for a start. His father was in the Army before him: and the 36-year-old was himself a sapper with the Royal Engineers for three years.

Then there is his willingness to work. He may be homeless, but he’s held down a number of jobs, including as a painter and decorator, a tyre fitter – and even a labourer on a pig farm. When you meet him, at York’s Arc Light hostel, he comes across as trim, fit, capable, and very, very smart. His poem is one of a number he’s written while at Arclight, says his girlfriend, Leeanne Shepherd, with whom he shares a room at the hostel. “He gets really deep into them,” she says. “He sits in his room and comes up with these poems.”

So why has this articulate and intelligent man made such a mess of his life?

He puts it down partly to having been unable to adjust to life after leaving the army. He came out at the age of 19, and felt lost. “I was always looking for a hierarchy to follow.” In the Army, he says, “you’re taught how to kill, but not how to live.”

Partly, it was his upbringing. His dad was a sergeant in the Ordnance Corps and as Graham was growing up, the family moved around. “I never really called anywhere home.” His parents divorced when he was 11.

And partly, he admits, it was his own inability to resist the temptations of drink and drugs.

When he left the army, he went to Banbury. But he fell in with the wrong crowd. “I seem to have a knack for it.” Drink and drugs – mainly amphetamines – dragged him down.

He left Banbury to try to escape, and came to York – only to fall in with the wrong crowd again.

Now, however, he is determined to turn his life around. He and Leeanne hope to get a flat together. “By Christmas next year, we will be in our own place,” she says. And Graham hopes that will give him the stability to get a steady job.

But he’s already been set up in a flat before now, and ended up back on the streets again. Why should things be any different this time?

“I’m getting too old now not to make a go of it,” he says grimly. Besides, there’s Leeanne. And now he has the drunk and drugs under control. The drugs are ‘very few and far between’, he says. And the drink? “I have a drink now and then, but I know when to stop – which was never the case before.”

RESEARCH by the Homelessness Monitor, a project run jointly by the University of York and Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh, suggests that homelessness in England is on the increase.

Young people and families will bear the brunt, it says.

Jeremy Jones, chief executive of the Arc Light hostel where Graham and Leeanne are staying, doesn’t find that surprising. Certainly, over the past 12 months, the average age of people needing the help of Arc Light has dropped, he says.

He has also noticed a longer-term trend. Over the past 13 years or so, the reason people end up on the streets has changed. Possibly it is the result of what he calls the “breakdown of the social fabric” – broken families, abusive childhoods, and so on. “The people that we see now tend to come from broken families,” he says.

Tracey* fits that pattern better than someone like Graham. Now 25, she was taken into foster care when she was six. Her parents had split up; she blamed her mum; and she took it out by rebelling against her.

After a couple of years, she returned to live with her mum, only to suffer abuse at the hands of a distant male relative. The abuse went on for more than four years.

She didn’t tell her mum, because the abuser threatened her. “He said if I said anything I would face consequences.”

Eventually her abuser was jailed. Tracey was fostered again, then met and went to live with a much older man.

She had children with him, and eventually they married. But they split in 2010.

She moved into a hostel with her children, until her ex-husband said she was an unfit mother, she says. The children went back to live with their father. She herself had a brief relationship with another man – then found herself sofa-surfing and eventually sleeping rough.

Her first night out in the open was a real shock, she says. She spent it beneath trees on the banks of the River Ouse. “It felt like the bottom had dropped out of the world. My life had changed from having a three-bed house with my ex-husband, to being on the street.”

She is now at Arc Light. She sees her children regularly, and hopes that she will one day get them back. But this first Christmas without them will be tough, she says.

Twenty-year-old Cavan Lund also comes from a broken home. He was adopted at the age of three because of family problems, and went to live in Keighley. His adoptive parents were the best parents he could have hoped for, he admits: and he went to a good state school.

But he was angry and rebellious. He wrongly resented his adoptive parents for taking him away from his own family, couldn’t be bothered with schoolwork, and had a problem with authority.

He started smoking ‘wacky baccie’, and getting into fights and other trouble. At the age of 16, his adopted father gave him an ultimatum. “He said ‘you can either go and get a job, or just go,” Cavan recalls. He chose to leave.

He hasn’t had a proper home since. He spent some time in Manchester, but left because of all the ‘crackheads’. He smokes weed, he says, but has a horror of harder drugs. “I’m scared of heroin because I’m scared I would like it.”

He too spent a while sleeping on sofas and friends’ floors; and eventually found himself on the streets, sleeping in places like York market.

Being on the street at this time of year is horrible, he says. “It makes you feel suicidal. You’re sitting there under a market stall at 3am with cardboard boxes on top of you, and you know you’ve got to get through until 8.30am.”

With a place at Arc Light, he feels he’s half-way towards turning his life around. At least he has somewhere to stay. But while he has applied for jobs, no one will take him. He hopes eventually to graduate to the Peaseholme Centre, then into shared housing. And if no one will give him a job then… “I’ve got an idea to open up my own shop in town. A souvenir shop.”

For now, he’s just glad to have a roof over his head. There are many out there in York who aren’t so lucky, he says. “I could name you 40 homeless people in York.”

Jeremy Jones says that yes, there is a waiting list for places at Arc Light.

And he worries that things will only get worse as benefits cuts kick in in April.

“The welfare reforms are going to be crippling for families and for single homeless people,” he says. “It is the future that is bleak.”

* Tracey’s name has been changed.

Benefit cuts

There have been a number of cuts in benefits already in austerity Britain which have impacted on housing. More will come in next April.

Introduced already:

• Scrapping of Local Housing Allowance excess payment of up to £15 a week (previously paid to those whose weekly rent was less than the Local Housing allowance rate)

• Local Housing Allowance payments reduced, costing people in York about £12 a week on average

• Incapacity benefits being phased out and replaced with Employment Support Allowance, which fewer people qualify for.

Changes to come in from April 2013

• A new Universal Credit to replace support allowances, incapacity allowances, child tax credits and housing benefit. Universal Credit will be capped at £500 a week, including housing benefit. Government figures suggest households on benefits could lose £93 a week on average

• The housing benefit element of the Universal Credit will only cover the size of a property a tenant is judged to need. People in properties judged too big for them will either have to top up the housing benefit themselves, or move. Housing benefit will also be paid monthly rather than weekly, and direct into tenants accounts rather than to local authorities – leading to worries some people may not manage their budgets and could fall into rent arrears.

• Single people under 35 renting in the private sector will be expected to share a house. At the moment, this applies only to single people under 25

• Council tax benefit to be replaced by a new support scheme administered by local authorities – with a 10 per cent saving met by councils.

• If you are worried about how benefit changes may affect you or your family, call the CAB advice line number on 08444 111444.

• If you are worried about someone who is sleeping rough and want to ensure they can get help, call the new Street Link number on 0300 500 0914.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel