This week Mike Sansbury, of The Grove Bookshop in Ilkley, reviews Wilfred Owen by Guy Cuthbertson Yale, £25

Many people will feel that they know everything there is to know about Wilfred Owen; he is the subject of two excellent books by Jon Stallworthy and Dominic Hibberd but, as Guy Cuthbertson points out, while a man can have only one gravestone, there is always room for another biography. It is more than ten years since the last and there is much to recommend in Cuthbertson’s addition to the vast fund of Owen material.

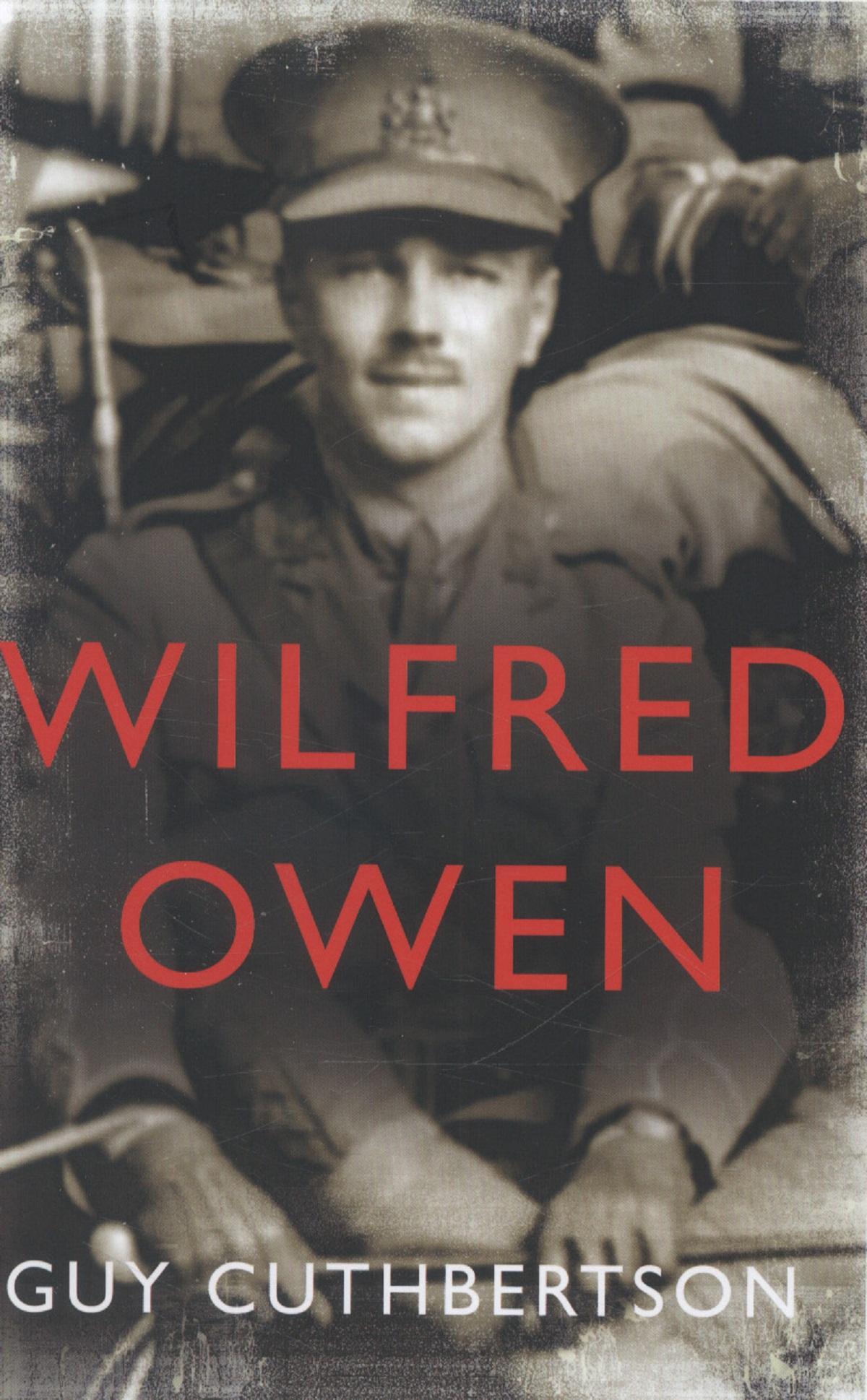

More than anything, this is an attempt to breathe life and colour into the famous sepia images of the unsmiling soldier poet. Cuthbertson looks in great detail at the places – Oswestry, Shrewsbury, Birkenhead – which formed the man and those which, like Edinburgh, Ripon and Scarborough, gave him time and space to write.

Contemporary accounts, writers’ memoirs and even the author’s collection of vintage postcards combine to give a picture of the world in which Owen spent his 25 years.

There are illuminating sections on Bordeaux, where the budding poet was able to escape his family and begin to develop as an individual, and Reading, where his studies provided a pale shadow of the Oxbridge life to which he aspired and which he seems to have thought was his due.

There is much speculation on many aspects of Owen’s character – his sexuality (he seems to come across as an almost asexual, Lewis Carroll type), his accent (there are no recordings of this famous 20th century poet) and even his facial hair, are all investigated in detail – and this can become a little comical.

In a war where moustaches and lice were present in almost equal numbers it is hard to see Owen’s as one of the century’s most famous.

Another aspect of the book which has been called into question is Cuthbertson’s tendency to enter the realms of “what if,” but in my opinion this often adds to the rounded picture that he is trying to present.

One of Owen’s desires was to mix with other poets and people of influence and, lacking the connections of Siegfried Sassoon and Robert Graves (both of whom come across here as slightly patronising and envious) he seems forever on the margins of literary society. Only the Sitwells and Charles Scott Moncrieff are shown to accept Owen as he is, and we might experience some schadenfreude in Sassoon’s 1950 remark, quoted in a footnote: “The fact that I knew him seems to be my main claim to distinction these days.”

We must not forget that this is the biography of a poet, and Cuthbertson has been allowed to quote liberally from Owen’s work. His examination of place, accent and character bears fruit in aiding our understanding of the language of the poetry and the various references therein.

The deepest impression which I took from this book, however, was of Owen’s personality. Cuthbertson draws a picture of a shy, self-contained young man whose determination to be known as a poet enabled him to overcome his humble background, his close, almost oppressive relationship with his mother and the distance at which he was held by his literary peers.

To comrades and acquaintances he seems to come across as withdrawn, but perhaps the most telling image in this book is a rarely-seen photograph of Owen, newly enlisted in the Artists’ Rifles, grinning widely like a young man on the verge of a great adventure. In a few short years he would have achieved his destiny.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article