WE’RE paying a second visit to Coney Street this week, courtesy of oral historian Van Wilson’s latest book, York’s Golden Half Mile.

It is a book packed with memories from people who worked in Coney Street, or who went shopping there, or visited the cinema.

In our first look at the book, a few weeks ago, we concentrated on Coney Street’s heyday as the centre of high fashion in York, when smartly-dressed women would parade up and down the street to visit its boutiques and fashion houses.

Today, we focus on another aspect of the street’s history – its newspapers.

As readers of this newspaper will know, until 1989 Coney Street was the home of the Yorkshire Evening Press.

In the course of researching her book, Van and her team interviewed a number of former Press staff who worked in the Coney Street offices.

They include John Avison, who began his career at The Yorkshire Evening Press in the 1960s while still in school uniform.

He was taken on as a part-time junor editorial assistant – at a wage of ten shillings (50p) for six hours a week.

John’s late father, Frank, also worked at The Press, having joined as an apprentice typesetter in 1917. He remained with the company for more than 50 years.

In Van’s book, John talks vividly about life at The Press back in his father’s day, towards the end of the First World War.

“Behind the upper storeys of the Press office lay a labyrinth of decaying, rat-infested buildings, where the work was hard and much of the equipment was primitive,” he said.

“In 1917, newsprint would arrive by train and be brought from York railway freight yard by a horse-drawn dray.”

His father had joined straight from school in 1917.

John said the employment prospects for school-leavers were poor. “With so many men at the Front, firms found it a struggle to continue. A teacher at St Barnabas’ School had spotted his talent for English and suggested that here was a likely lad for a job in newspapers.”

The young Frank passed a spelling and punctuation test and was taken on.

“The hours he had to work and the remuneration would make today’s school leavers shudder,” John said.

“The only days off he could look forward to were Sundays, Christmas Day, and Good Friday. His pay? Just five shillings (25p) a week.”

Frank’s first job was helping to check proofs. Gradually, he was taught to use the hot metal linotype machine, used for typesetting. After six months probation, he was given a seven-year apprenticeship.

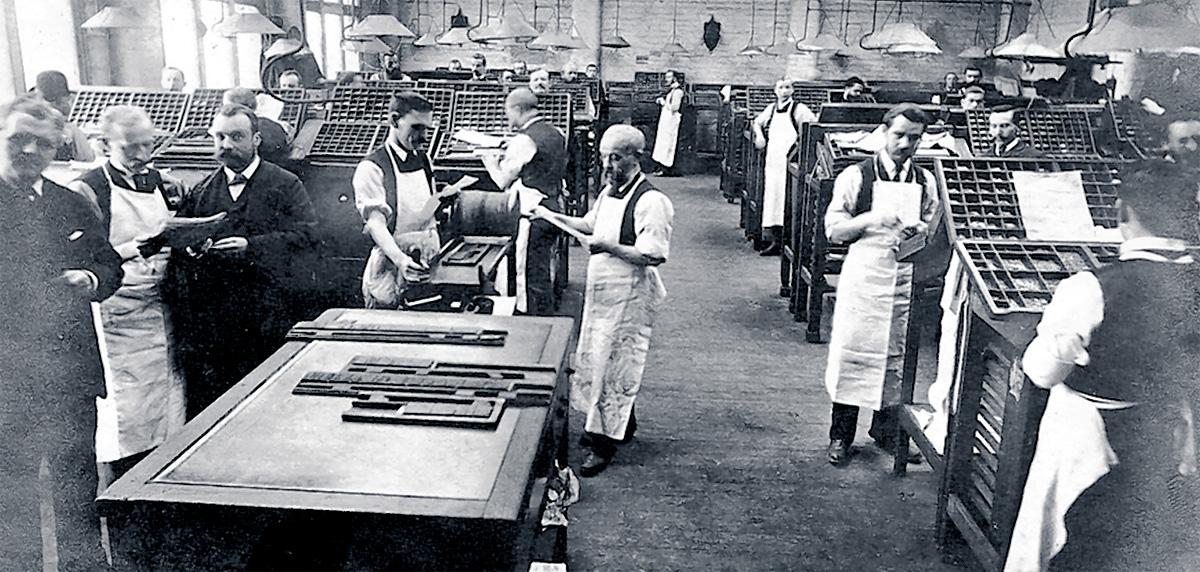

John said: “The apprentices found themselves young men among many older men, as all those of military age were away serving King and country. “The old timers would wear bowler hats, waistcoats and high choker collars. They were inveterate snuff takers and tobacco chewers.”

In those days, the newspapers were printed in Coney Street. “The whole operation was steam-powered, the rows of linotype machines being driven by an elaborate system of belts and pulleys,” John said.

“A fan revolving high up in the ceiling was the only ventilation in a room where in summer temperatures topped 100 degrees F.”

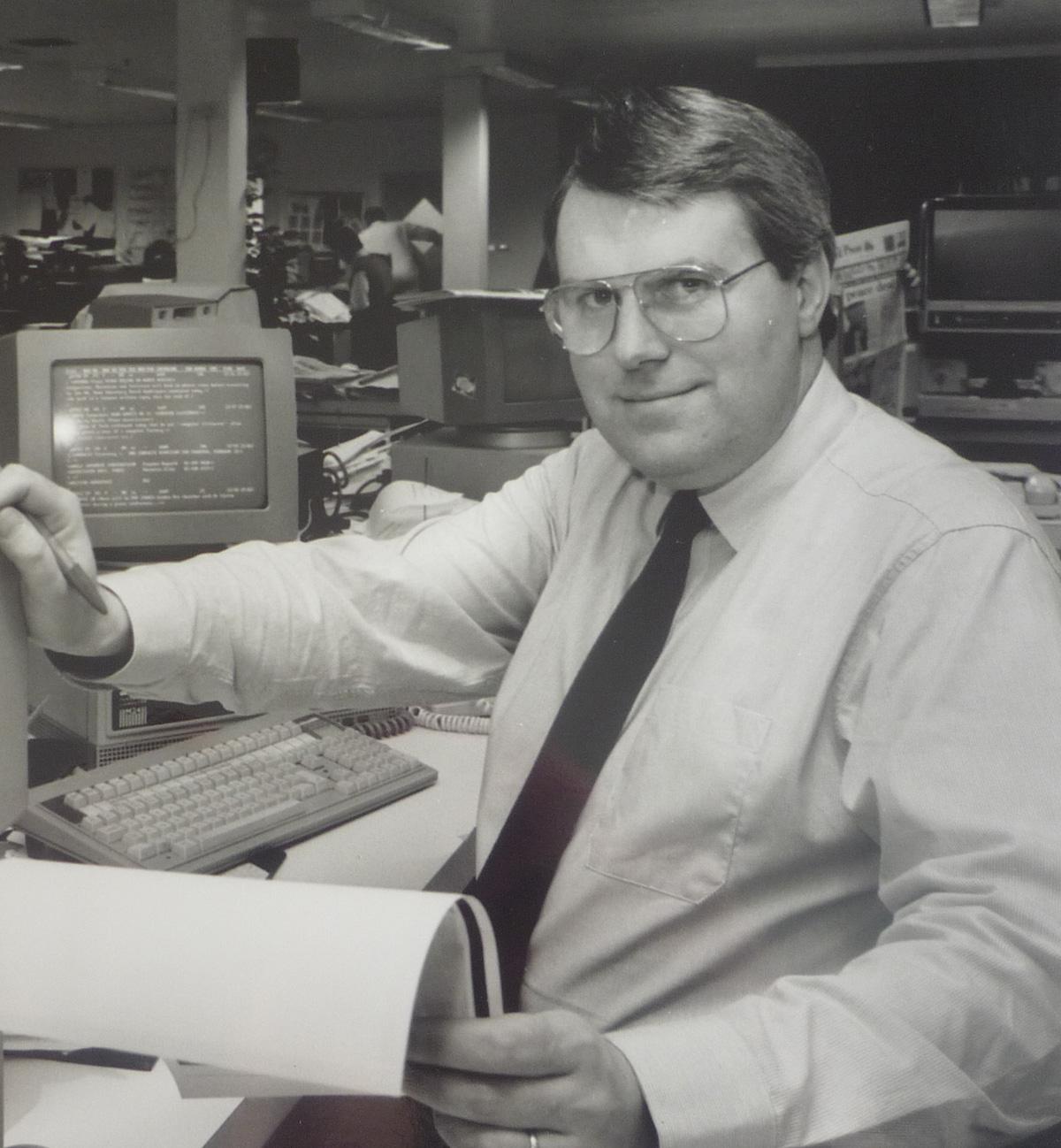

Decades later John himself worked as a reporter on the newspaper his father had been with for so long.

As a young reporter, his working day could start at about 8.30am and, if he was covering a York City Council meeting, finish at 7.30pm.

“On one occasion, I’d been to cover The Exorcist at the ABC in Piccadilly, a very controversial horror film. I remember walking back through the labyrinthine corridors of the office in Coney Street, with the tick tick tock of the clock, and sitting at my Remington typewriter. That building could be very, very spooky in the middle of the night,” he recalls.

As it happened, John did need rescuing that night – although not from a vengeful, possessive spirit.

He was tapping away merrily on his Remington, he recalls. “My finger slipped between the keys, my wedding ring got jammed, and with my free hand I had to dial 999 to get the fire brigade to come and release me.” He doesn’t say whether the story made the following day’s front page.

York’s Golden Half Mile is full of memories.

Perhaps one of the most remarkable people to be featured in the book is Moyra Johnson. Born in 1915, she was one of the country’s first women glider pilots – Van’s book even has a photograph of her in the 1930s, with her glider.

Moyra has since sadly died, but she told Van her connection with Coney Street was that she used to visit the old Picture House cinema.

In fact, her connection became a little more personal than that.

“I had a boyfriend called Philip and he took me to the Picture House in his car,” she said. “He went away to park it and he left me in the entrance talking to the cinema manager Ernest Johnson.”

The next day she and Philip went to a ball. Ernest was there. “Philip got drunk, so Ernest took me home. We were married within the year!”

Ernest had taken over management of the Picture House in the mid 1930s, when it was still a silent cinema. “It had the orchestra there,” he recalls.

The most popular film he ever showed was one starring Shirley Temple. It was supposed to be a children’s matinée, starting at 11am.

“About half past nine the police came in and said: ‘You'll have to start running this film’.” He asked why, and the police told him to look outside.

“There were kids right down Coney Street, just queuing.”

• York’s Golden half Mile: The History of Coney Street, by Van Wlson, is published by York Archaeological Trust, priced £9.99. It will be available from most local bookshops.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here