CONEY Street today, with its chain stores and mobile phone shops, is like pretty much any other high street in Britain.

But it hasn’t always been. There was a time, not so long ago, when its fashion houses, its small individual retailers, and the Mansion House and Guildhall which still stand at one end, marked it out as something special.

Coney Street was known, in fact, as “York’s golden half mile”. Fashionably dressed ladies would parade up and down; the street was home to a daily newspaper (The Yorkshire Evening Press); the Lord Mayor of York lived (and still lives) there; and kings and prime ministers were entertained at the Mansion House.

York oral historian Van Wilson has used the street’s nickname for the title of her latest book. York’s Golden Half Mile: The Story of Coney Street, is just that – a history of the street in the words of the people who once lived and worked there.

There is a brief introductory chapter in the street’s early years – it began life in Roman times as a street running parallel to the south western wall of the old Roman fortress, writes Van, and by 1150 was known as Cuning-strete, or King’s Street.

By 1308, it was already being described as York’s principal street for business: and its position was cemented when the The Guildhall was built in the mid- 1400s, and then, in the early 1700s, the Mansion House.

All of which is fascinating. But it is when Van’s story reaches living memory, and she can quote verbatim from people who lived and worked here from the early 1900s onwards, that the book really comes alive.

Dozens of people were interviewed for the book – those who worked at the Mansion House and Guildhall; former employees of stores such as Leak & Thorp, John Grisdale and Kirby and Nicholson; and one-time staff of the Yorkshire Evening Press.

June Dandy joined the Leak & Thorp hairdressing salon as an apprentice in 1942, straight from school. She was interviewed by the chairman, William Collinson, and started at five shillings a week.

“I’d been there just over a week and we had the Blitz on York,” she recalls. “I was on my cycle and I got to St Helen’s Square and there was glass all over. I was carrying my bike most of the way along Coney Street.”

A salon at the other side of the street, Grace and Hardy, was bombed out. “They asked our directors if they could share our salon until they got a place in Stonegate. I remember Mr Collinson saying ‘Just watch our clients, see they don’t go over there’.”

By 1948, things were “starting to improve after the war”. There was to be a fashion parade, featuring a new type of perm. June was volunteered to be a model, and after at first protesting, agreed when she was told she’d get to wear a lovely new evening dress. “It was deep purple or burgundy… The buyer from the gown department came and brought this beautiful dress. I said ‘right’, just to wear the dress!”

David Wilson’s father, Jock Wilson, was caretaker at the Guildhall, and lived in a flat above the offices. “He came there in 1925. The cook and maids lived in the Mansion House, but the butler didn’t. My dad was the mace bearer when Arthur Wright was sword bearer.” Jock is to be seen with his mace in two celebrated photographs taken on the steps of the Mansion House in 1925: one showing Lloyd George receiving the freedom of the city; and one showing the Duke and Duchess of York, who later became King George VI and Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother).

As a boy, David – who was born in 1931 – used to go fishing with his dad in the Ouse behind the Guildhall.

He remembers Coney Street as being “two-way traffic, it was very pleasant. The horse and cart would come down from the railway delivering goods. I remember Potter-Kirby, who owned Kirby Nicholson’s, an outfitters. I used to whistle at the girls in the room at the back.”

He and his family were still living in their flat in the Guildhall on the night of the York Blitz.

“When the raid started I was in bed. There was a bang and I ended up on a chair in (my sister’s) bedroom by the window. My friend, Eric Walker, in Blake Street, they lived upstairs and the front door was blown off and was in the middle of the road.”

Just down Coney Street from the Mansion House, where City Screen now stands, was the old Yorkshire Evening Press building.

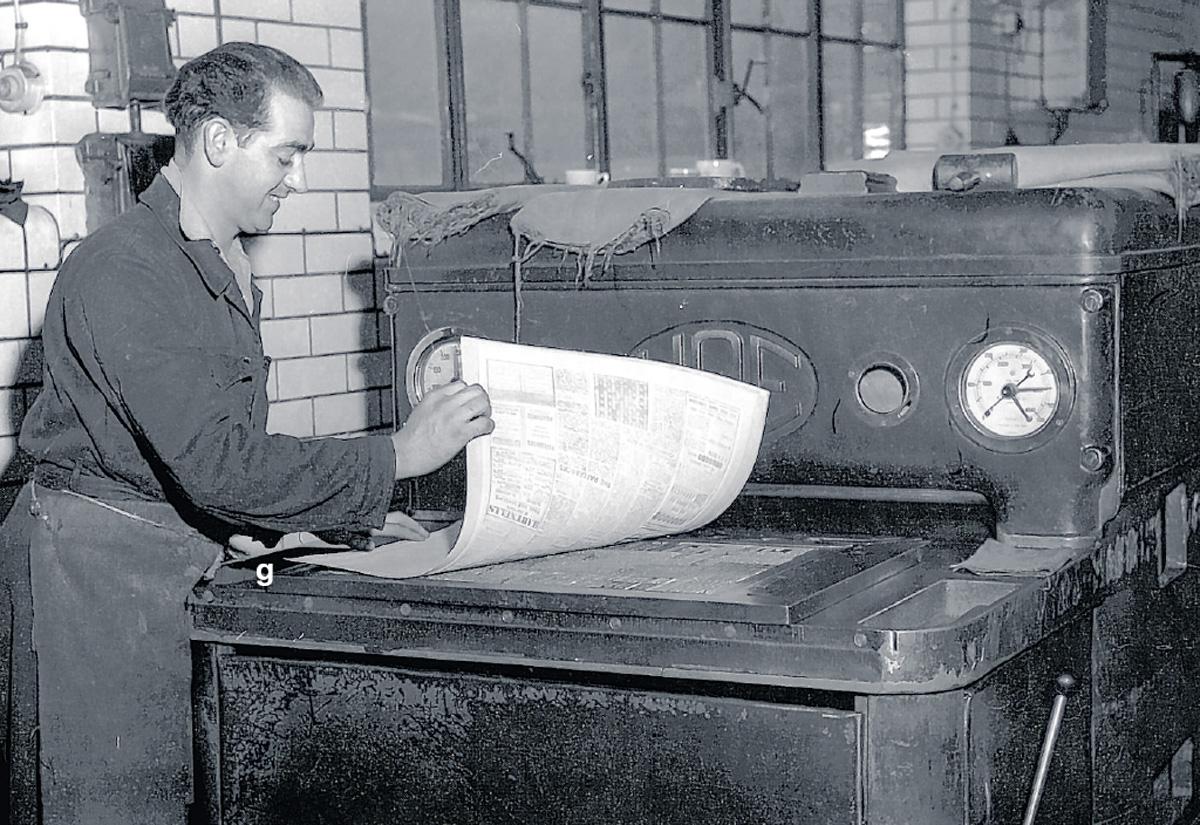

Arthur Winship worked as a plate-maker at the Yorkshire Evening Press in Coney Street most of his working life, until being made redundant in 1987. His son, David, had a Saturday job at the Press from 1977.

“There’d be a team of 11, 12 and 13-year-olds. I was the youngest. It was an enormous room, and it had loads of clocks on the wall.

“There was a dividing room, you could look through the glass, and the teleprinters were going with the latest football scores and they tore them off and put them in the dividing door.

“My job was to pick it up, roll it up, put it in this glass tube, and then it was like a suction system, it shot off. You could hear it going to another room.

“The most important job was writing the football scores, if you made a mistake, that was what would go in the Press… “When I look back it was quite a cool place to be, quite exciting.”

• York’s Golden half Mile: The History of Coney Street, by Van Wlson, is published by York Archaeological Trust tomorrow, priced £9.99. It will be available from most local bookshops.

Van will be at WH Smith in Coney Street from 10am to noon on Thursday to sign copies of the book.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here