THERE is unrest in York's original 'garden village'.

The Joseph Rowntree Housing Trust wants to build a new 175-bed care home in New Earswick. Its proposals would also involve alterations to the Folk Hall, as well as demolishing the former library and tennis clubhouse, and relocating the play area.

The housing trust's executive director John Hocking says the development will be very much in the spirit of Joseph Rowntree's original garden village.

"Our plans for New Earswick will mean that we can provide more homes for older residents who want to downsize, release much-needed family homes and make the village's public areas better for residents of all ages," he told The Press.

Nevertheless, by last week there had been more than 100 written objections from people who feared the proposals could see much-loved green space under threat. Tennis club members were also angry at the thought of losing their courts - even though the housing trust said it was working with the club to explore alternative venues.

Given the upset in Joseph Rowntree's model village, local historian Paul Chrystal's new book could not be more timely.

Old Haxby and New Earswick tells the story of these two very different villages, mainly through Paul's extensive collection of old photographs.

There are some wonderful photos in the book of the early days of New Earswick - including the three we publish here today, which serve as a reminder of Joseph Rowntree's original vision.

In case you've forgotten: Rowntree began building New Earswick in 1904 as an alternative to the overcrowded, insanitary slum housing that was at the time virtually all that was available to workers in York.

He bought 150 acres near Earswick, and planned the model village, according to the Joseph Rowntree Housing Trust's own history, as a "self-governing community, with its own Folk Hall, Village Council and school."

That same history continues as follows: "The building of New Earswick was an attempt to create a balanced village community that was open to any working people... At his (Joseph's) insistence, houses had gardens with fruit trees and enough ground to grow vegetables.

"The Trust deed of the Joseph Rowntree Village trust (set up in 1904 to build and manage New Earswick) safeguarded generous open green space. All the grass verges were planted with trees - and almost all the roads are named after trees."

The photos of New Earswick included in Paul's book include a lovely one of estate workers cleaning the streets of the new model village in 1910. One of the workers, pictured centre, was George Smith, who had been at New Earswick since 1905. Before then, Paul notes, he had worked as an apprentice at Backhouse in Acomb, the 'celebrated landscape gardeners who won a reputation as the Kew of the North."

There is also a photograph of Carnival Day in the same year, 1910, with villagers gathered outside on the green in their smart, late-Edwardian Sunday best. And, as if to underline how green and leafy this garden village was, there is also a lovely photograph of Chestnut Grove, probably taken in about 1920.

It shows mothers pushing young children in prams along a shady avenue. Sun dapples its way through the leaves to splash onto the road. "The early streets in New Earswick were a world away from York's Victorian Terraces," Paul notes. And so they were. Most of us probably don't realise these days just how radical and progressive Rowntree's original vision was.

From New Earswick to the very different village of Haxby.

This, as the title of Paul's book suggests, is a good deal older than New Earswick. It is, in fact, mentioned in the Domesday Book, when it was home to 'seven villagers and three ploughs'. The value of the village, Domesday Book records, had been 20 shillings before the Norman Conquest.

By the time the research for the Domnesday Book was done 20 years later, this value had halved, to just 10 shillings. "The devaluation was a result of the depredation wreaked by William the Conqueror's Harrying of the North - his scorched earth campaign to subdue revolting northerners," Paul writes.

There weren't many cameras around in 1086, of course, so Paul's photographic history mainly covers the last few decades.

His book includes some cracking old(ish) photos of Haxby, including one of the new swimming pool at Ralph Butterfield County Primary School being opened by Haxby's own international swimmer Pauline Clarkson in July 1964. The pool was renowned for being cold. Paul quotes an anonymous Facebook comment: "It was bl**** freezing and so was the metal bucket you had to stand in before getting in the pool. Oh yes and the outside changing rooms - complete with peep holes!"

The school itself had been built, Paul notes, on Sharp's Field, a football pitch named after York pawnbroker William Sharp. It was named in honour of Ralph Butterfield OBE, a prominent North Yorkshire educationalist who had won the military cross at Passchendaele.

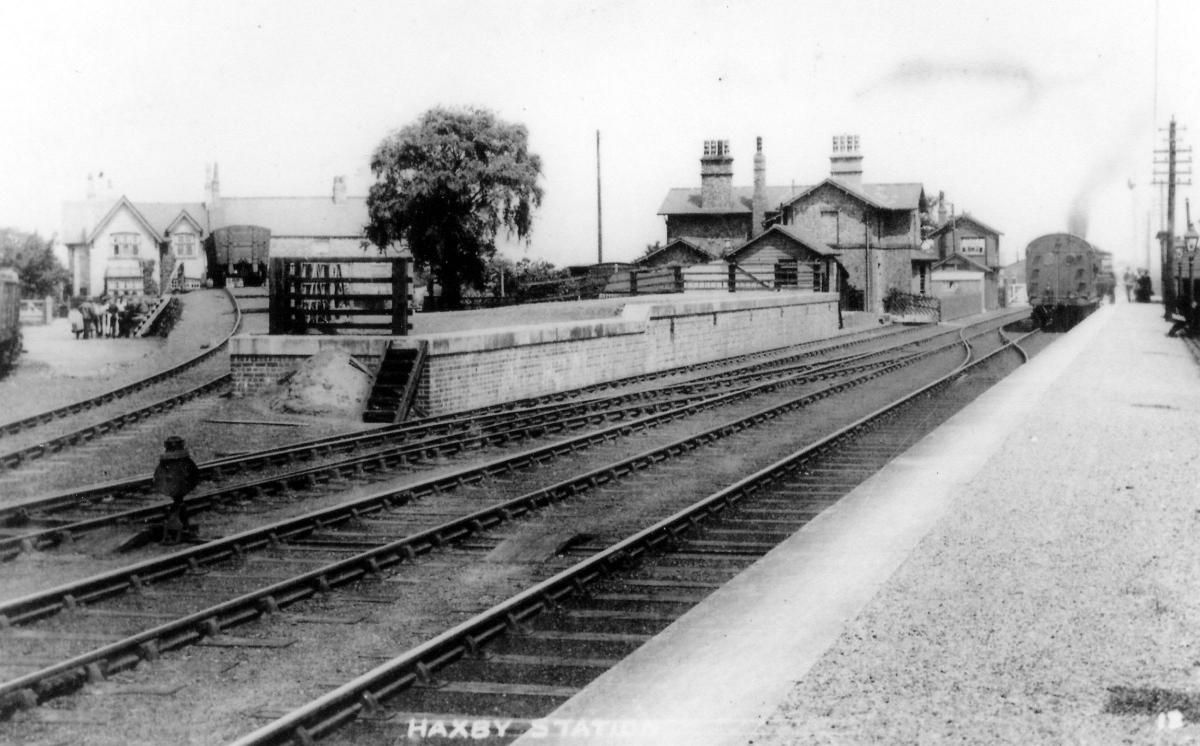

Another photo shows Haxby Station, which used to be where Pulleyn's garage now is on Station Road, Paul writes. It opened in 1845, and closed to passengers in the 1930s, although it remained open for freight and coal for some years.

Paul has managed to dig out an old York Herald cutting from December 12, 1864, which reports on the inquest into a dreadful accident involving the stationmaster, Thomas Hawcroft. He had been run over by a wagon while trying to help his porter, and later died after his foot had been amputated, The Herald reported. Verdict: accidental death.

Notwithstanding such a dreadful accident, in its heyday Haxby was a busy local station. Typical 'cargo' included boxes of fish, calves, animal feedstuffs, straw, grain ... and soldiers on the way to Strensall, reports Paul.

* Old Haxby & New Earswick by Paul Chrystal is published by Stenlake Publishing, priced £10.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here