As the team in the eating disorder unit at The Retreat in York receive national acclaim, health reporter Kate Liptrot learns how the work being done there is changing lives.

A SUNNY painting of a woman sitting on a bench outside The Retreat would be unremarkable were it not for the heartfelt caption written by her husband.

“Thank you so much for your work with Jackie. Your work has been wonderful and has changed our lives.”

Hanging feet from where it was painted, on the wall of the busy staffroom of The Retreat’s eating disorder unit – known as Naomi – the picture is only one of the many moving success stories for the unit, last year named as team of the year by the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Overlooking the lush grounds of the Heslington Road hospital and with high-ceilinged fading hallways lined with antique furniture gathered over the decades, the welcoming 15-bed female unit could almost be a country hotel, were it not for the wall displays or the personal effects in women’s rooms.

It is a calming environment for people who can arrive at the hospital at a desperate stage in their lives.

New admissions are sometimes so dangerously underweight or unwell they have to be immediately confined to bed and kept at close quarters until they are medically stable.

Starving and malnourished patients have to be carefully reintroduced to food, as the potentially fatal refeeding syndrome can lead to complications including heart failure.

“Starvation doen’t just make you thin but affects every organ,” Janet Dodsworth, the clinical team manager for Naomi said, frankly adding: “The risk is you drop dead, and I’m not just being dramatic.”

But while staff are fundamentally working to save the lives of patients, the emphasis in Naomi is on long-term recovery.

Whereas the objective of some hospitals would be to stabilise weight – sometimes even through of force feeding and tranquilisers – Naomi works to put responsibility in the hands of its patients by asking them to examine the causes of their behaviour and giving expert support to let them take control of getting better.

“It’s a really difficult disorder to treat,” said Naomi’s consultant psychiatrist, Dr Andrea Brown.

“If you don’t teach people skills to manage their eating, it’s not going to work.

“For me, a success is having a meal with your family, making a sandwich and eating it. It might be going to college and getting a job. Quite a few of our patients really achieve this.”

Considered a serious mental illness, some 1.6 million people in the UK are affected by an eating disorder such as anorexia, bulimia or an eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS), including binge- eating.

But by the stage patients receive an NHS referral to Naomi, other treatments will have been tried and, as well as suffering from complex eating disorders, patients could have an additional diagnosis, such as obsessive compulsive disorder.

Overwhelming demand means there is a continual waiting list of patients from all over the country, with the particularly high-risk having to be prioritised.

The support and deep sense of calm on the unit wasn’t initially a soothing experience for 45-year-old Veronica*.

Admitted to Naomi in October following a long history of binge-eating and restricting food, which means she has struggled to keep her weight down, Veronica said she felt out of place and stifled by the early lack of freedom on the programme.

She said: “In the early days I did phone my friends and think: ‘What am I doing here?’ There have been times I have really struggled and thought: ‘I don’t want to do this’.

“I found it difficult when I first got here because of the restrictions over where I could go.

“The fact a lot of people have anorexia and are young made me feel like a fish out of water but, as someone said to me, it’s not an eating disorder but disordered eating.

“I couldn’t get my head around sitting down for a meal three times a day as a part of structured weight loss.

“But you can’t deny it works when you see the evidence you have lost weight.” Veronica said the patience and non-judgmental nature of the staff have significantly boosted her self-confidence.

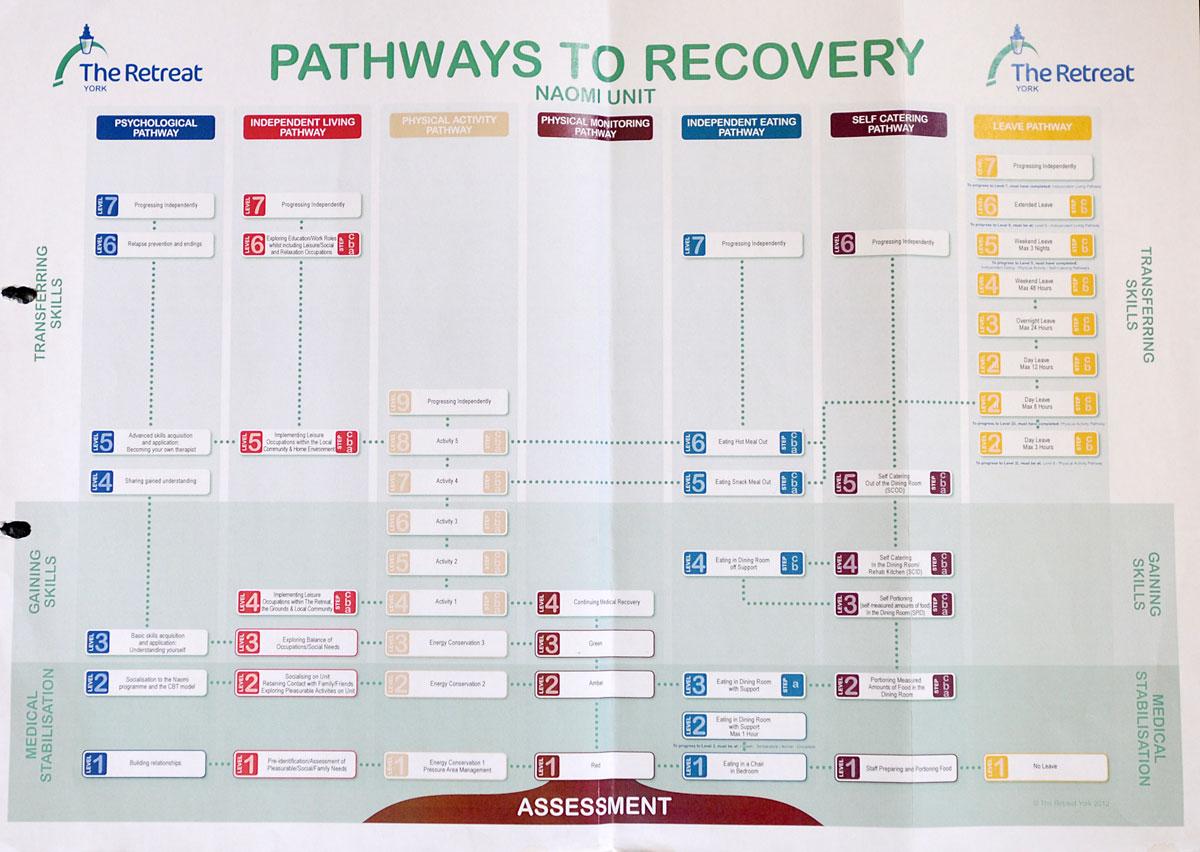

As with all of the women – who are aged from 18 to 65 and stay in Naomi an average of eight months – Veronica has taken part in a carefully structured “pathways to recovery” plan which is supported by a psychiatrist, psychologist, dietician and occupational therapist, with regular assessments.

In what is for many a painstaking process of learning to eat properly again, women will work through clearly defined levels, from the basic stage of eating on a chair in their bedrooms to the aim of eating out independently, and from bed rest to days out and taking part in yoga and swimming.

They will also take part in timetabled group activities, including cognitive behavioural therapy.

“If you just make someone eat, even though they look better, they go back to their previous behaviour,” Janet said, reflecting on the success of the combined programme.

“Those behaviours serve a function and if you don’t understand the behaviour how can you change it?”

*Name has been changed to protect identity.

Understanding all the different disorders

THIS is Eating Disorders Awareness Week, which aims to raise awareness and understanding of the conditions.

• The National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence suggests 1.6 million people in the UK are affected by an eating disorder, of whom about 11 per cent are male.

• However, more recent research from the NHS information centre showed up to 6.4 per cent of adults displayed signs of an eating disorder

• It is estimated that of those with eating disorders: ten per cent of sufferers are anorexic, when people restrict food, 40 per cent are bulimic, which is characterised by binge-eating and purging, and the rest fall into the Easting Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS) category, including those with binge-eating disorder.

• About 46 per cent of anorexia nervosa patients fully recover, with a third improving, and 20 per cent remaining chronically ill. Similar research into bulimia suggests that around 45 per cent of sufferers make a full recovery, 27 per cent improve considerably, and 23 per cent suffer chronically.

• The charity Beat, urges people who may have eating disorders to tell their GP as soon as possible.

• Figures from the Health and Social Care Information Centre have shown a rise of eight per cent in the number of hospital admissions for eating disorders in the 12 months to October 2013. In York and North Yorkshire numbers have risen by a third.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here