It is eight years since Daniel Wall and his friend Kevin Mulgrew were murdered in a Gillygate flat by heroin addict John Paul Marshall. Now Daniel’s mum Rosie and sister Becca have set up a Facebook campaign calling for life to mean life. They talked to STEPHEN LEWIS about the son and brother they will never forget

ROSIE Wall heard a knock on the door and opened it to find a policeman standing outside. At that moment she knew something had happened to her son.

She had been trying to contact Daniel since the Monday. But she couldn’t get through on his mobile phone. Something was wrong. “Even if there was no credit on his phone, he always left it switched on,” she says.

By the Thursday, after three days of trying to get hold of him, she had reported him missing to the police. “It was so out of character.”

Now it was Saturday at 10am and a policeman was at her door. Rose had read that somebody had been killed in a flat at Gillygate. Now the awful truth dawned. “I just knew,” she says.

The policeman asked if he could come in. “I said ‘It’s Dan, isn’t it?’ and he said ‘Let me come in, Rosie.’ I said, ‘It’s Dan, I know,’ and he said, ‘I’m afraid so’.”

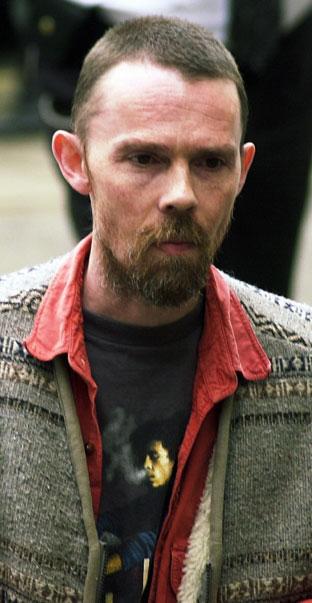

A year later, drug addict and dealer John Paul Marshall went on trial on two counts of murder. Only then did the full horror emerge of what had happened in that Gillygate flat on December 1, 2003.

Daniel and his friend, Kevin Mulgrew, both heroin addicts, had been staying in Marshall’s cramped council bedsit. On that Monday morning, Marshall woke up and watched as they lay in what the court heard described as a drug-induced slumber in the living room. He then used a heavy light fitting to bludgeon the two men to death.

Marshall, 42, himself an addict and dealer, fled to Holland. The bodies of Daniel and Mr Mulgrew lay undiscovered for three days, until they were found on the floor beside a radiator in Marshall’s flat on December 4.

All the time that Rosie had been trying to contact her son, he had been dead.

Rosie and her daughter, Becca – Dan’s sister – still remember their last conversation with him. He rang the Thursday before he was murdered to say he was no longer staying at the Cemetery Road flat where he had been living. “Mum said, ‘Why don’t you come home?’” Becca recalls. “He said he couldn’t leave Kev. He was loyal, that’s how I would describe him.”

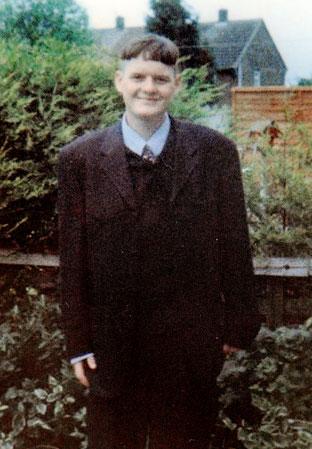

Family pictures of Dan – who was 27 when he was killed – show a neat young man with a cheeky smile. That was her son, Rosie says. Even when he was in the grip of heroin addiction, he was always clean and tidy.

He was described in court at Marshall’s trial as a drug dealer. But that wasn’t true, Rosie insists hotly.

“Dan was not a drug dealer!” she says. He was a heroin user, yes, but not a dealer. “What he did was act as a runner. He drove them around. He did that so he didn’t have to go stealing to pay for his habit.”

Becca says she didn’t recognise the person being described in the trial as her brother. “Dan didn’t have a bad bone in his body.”

Rosie has said in the past that Daniel’s life started to go wrong when his cousin Tim committed suicide at the age of 20. A couple of weeks later, his grandmother died.

But while he had his problems with drugs – and even spent some time in prison – with his family, he remained the loving son and brother he had always been.

“He would come around, and he would put his hand on top of the kitchen door and he’d say, ‘Hiya, do you want a cup of tea?’” Rosie recalls. “And then he’d sit down and he’d read the Daily Mirror and The Press from front to back.” He particularly enjoyed reading the court reports, Becca adds. “He’d say, ‘Hey, mum! Look who’s in court today’.”

Her brother was a joker with a cheeky sense of humour, Becca says, but he cared about his family. Rosie says when his father, Jeff, had to go into hospital in January 2003 following a heart attack, Dan was a rock. “He went every night for six weeks to see Jeff.”

Despite his addiction, Daniel also had a wise head on his shoulders, his family say. Rosie – a tireless worker for the local community in Chapelfields – once admitted to her son that she felt guilty that she had allowed him to get involved in drugs.

“And he said to me: ‘Mum, don’t blame yourself. It’s nobody’s fault but my own. I got myself into it’.”

Marshall was arrested by police in Holland on December 23, and was extradited back to the UK in June 2004. His trial began in December, 2004, almost exactly a year after Daniel and Mr Mulgrew were murdered.

That trial was a torment, Rosie and Becca say. In court, Rosie had to sit with Marshall’s family behind her. “We were not allowed to look at them.”

She was forced to listen to her son being described as a drug dealer, and says she was made to feel like a second-class citizen because her son had been an addict.

Marshall showed not one bit of remorse, she says. During his trial, he was asked what was going through his head when he killed the two men. “I wanted them dead,” he replied.

The court was told that Marshall was suffering terrible withdrawal symptoms when he killed Daniel and his friend.

Rosie doesn’t believe that for a moment. “He said he had had some heroin in the early hours, and by 11am he was ‘rattling’ [going cold turkey],” she says. “He wouldn’t have been.”

Leaving the court after Marshall was found guilty of double murder, she turned, looked at her son’s killer and screamed: “Rot in hell!”

Marshall was jailed for life and told he would serve at least 18 years. But if Rosie and Becca hoped that the end of the trial would bring closure, they were mistaken.

It doesn’t get better, it only gets worse, Becca says.

“You’ve got the trial, and unpleasant as it is at least it is something to focus on,” she says. “Then you get the sentence, and at the time you’re satisfied with the sentence.

“But then you start to feel: 18 years for two lives? How can that be? Dan had more than 18 years of his life to lead.”

What’s more, the family suddenly found themselves on their own. As they prepared for the trial, they had had the support of a police family liaison officer. After the guilty verdict, Rosie says, he turned to her and said ‘That’s it; I’ve finished my job now.”

The family was left to try to pick up the pieces. But people don’t understand what it is like to have had a son murdered, Rosie says. She puts on a brave front, but inside the anguish is never far away.

“The worst thing is when people say to you, ‘You have to move on’. You can’t. You’re always thinking, he would have been 35 now. Maybe he would have been married, perhaps he would have had kids…”

One of the biggest regrets Daniel’s family have is that they never got to see his body after he had been killed. They were advised not to.

“But we should have seen him,” Becca says. Sometimes, she adds, just imagining what he must have looked like is worse. And, because she didn’t see him, there’s always that tiny, niggling doubt in the back of her mind that maybe it wasn’t Dan, Rosie says.

Rosie has thought of leaving York. The memories here are too painful. Becca sometimes she finds herself drawn to Gillygate, staring at the flat where Dan died.

But why should the family leave? Becca says. “And anyway, wherever you are, it is going to follow you,” Rosie says.

Life should mean life

DANIEL’S family – Rosie, her husband Jeff, winner of this year’s Community Pride parent of the year award, and daughters Nicola, 37, and Becca, 32 – say they will never be able to forgive John Paul Marshall for what he did to their son.

It isn’t just the fact that he murdered Daniel so cold-bloodedly while he was asleep – it was his total lack of remorse. “He said to his mother that my son was scum,” Rosie says.

Becca agrees that she will never forgive her brother’s killer. “But I would like to know he is sorry.”

The fact that he was a drug addict himself, whose life had been ruined by heroin, was no excuse, Becca says. “There are other addicts out there, but they don’t all go around murdering people.”

It will be ten years at least before Marshall is even considered for parole. But even the thought of him one day being released horrifies the family.

That is why they have set up a Facebook campaign calling either for the return of the death penalty or for life to mean life. Becca even produced a YouTube video to promote the campaign.

Realistically, Becca accepts that capital punishment is not going to be brought back.

“But life should mean life, with no parole and no privileges,” she says.

In addition to their public Facebook campaign, Rosie and Becca have also set up a private site, which people are invited to join, where the families of murder victims can contact each other. That private site is called Families United Through Loved Ones Murders, and there are 37 families signed up to it already.

It can be a source of great comfort, being able to share your feelings with people who understand exactly what you are going through, Rosie says.

Families linked by the website are also able to keep an eye on each other. One mother whose son had been murdered posted a comment saying she couldn’t cope, and that her life was over.

“One of the group rang the police, who went around and made sure she was all right,” Rosie says.

Occasionally, however, the sheer intensity of the site can be overwhelming, Rosie admits.

“Sometimes, when you’re reading what people have posted, I think, I can’t cope with this, and I have to come off.

“But yes, it helps. I wish there had been something like this for us eight years ago.”

• To visit Rosie and Becca’s public Facebook campaign page, visit on.fb.me/vJQGaY

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article