French veterans who flew Halifax bombers from RAF Elvington during the war returned yesterday for an emotional visit. STEPHEN LEWIS joined them

LUCIEN MALLIA stood next to the tail-end turret of a reconstructed Halifax bomber at Elvington and the memories came flooding back.

On a dark night more than 65 years ago, then a young French airman, he was sitting inside one of these turrets, the rear gunner on a night-time mission to bomb Germany, when his Halifax was pounced on by two German fighters.

They had almost reached their home air base of Elvington when the attack came.

“It was the March 4, 1945,” he said, his English halting but clear. “About two at night. The two German fighters attacked. I saw the first fighter. And then I saw our right engine was burning.”

Lucien’s pilot managed to bring the aircraft down in a controlled crash landing. Sitting in the back of the plane in his isolated rear turret, Lucien could easily have been trapped and burned alive. He’d seen that happen to other rear gunners and had learned from their mistake.

He managed to turn the guns so that by the time his plane came down not far from Elvington, he was able to open the emergency escape.

“If he didn’t do that, then my father wouldn’t have been born, and I wouldn’t be here,” said his granddaughter Virginie, who accompanied him and other French veterans on an emotional return to Elvington, the base where they had been stationed during the war.

Lucien, now 88, suffered burns, and a nasty injury to the head – the scar can still be seen today. But he survived to tell the tale.

And what a tale. Two French squadrons were based at Elvington during the last two years of the war: the 346 Guyenne and 347 Tunisie. They were renowned for their skill and courage, but flying bombing raids over Germany was a dangerous business. Half the French aircrew from Elvington were to lose their lives before the war was over.

Sitting in that rear turret, separated from the rest of the crew by a long length of fuselage, was a lonely place to be, Lucien admitted.

“I’m alone there,” he said, remembering. “It was a long way to get through to the others. But I stayed there. It was my job.”

Louis Hervelin, 89, another veteran who made the emotional return to Elvington yesterday, was a wireless operator on a Halifax. Unbeknown to him, while he was flying bombing missions over Germany, his young wife Berthe, 21, had been imprisoned by the Gestapo. He didn’t know until the war was over.

Luckily, the Nazis never knew that Berthe’s husband was a French airman. “Non! Nobody knew where I was – not even my parents,” he said.

When they weren’t flying on dangerous bombing missions, there was always time for a night out in York. And time, for some of them, for romance.

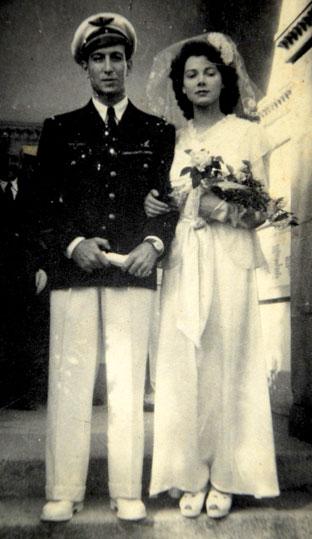

Lucien cut a dashing figure back then and at a dance in York a young woman caught his eye.

Her name was Audrey May Bellamy, from Fulford. “I went to a dance and saw her, this lovely girl,” he said. After that, they always danced together. She spoke no French, and he spoke only a ‘little’ English. But the romance blossomed. He used to cycle to Fulford to see her and eventually, she became his wife – Virginie’s grandmother. Because of the family connections, Lucien and his family come back to York quite often. But nothing was going to make him miss this week’s visit.

After the tour of the Yorkshire Air Museum yesterday, the French veterans and their families, along with assembled dignitaries and military brass, took part in a service of remembrance at the French memorial in Elvington village, where they were joined by children from Elvington Primary School.

Today, they will be at a special service at York Minster to dedicate a stone plaque in memory of the French airmen from Elvington who fought – and many of whom died – during the war.

The ceremony, at 11am today, will be followed by a parade past the Minster by English and French veterans, and a flypast of English and French aircraft.

Lucien was in hospital last week, after suffering heart problems. But there was no way he was going to miss the celebrations.

He had lost seven kilos though ill health, he admitted. “But I said to the hospital, ‘I have to go to York’.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel