THERE’S no market for Yorkshire humour, Peter Walker was once told. As a young policeman, he’d penned a book of funny stories about working the night shift in Whitby. Constable On The Prowl, he called it: but publishers just weren’t interested.

Deflated, he gave up. And some years later he passed on that “no market for Yorkshire humour” message to another would-be writer he met in a pub.

Knowing that Peter tried his hand at writing, the landlord came up to him and said “Can you see this fella? He’s written a book and wants to know what he can do about it.’ Peter chuckles remembering it. “There was this chap standing by the bar with a pint in his hand. I got a pint myself and then I said ‘what kind of stories are they?’ And he said ‘It’s a collection of funny stories about being a vet…’”

No prizes for guessing who it was. Back then, however, Alf Wight had yet to make a name for himself. There’s no market for Yorkshire humour, Peter told him gravely.

Thankfully, Mr Wight ignored that sage advice and, as James Herriot, went on to write the wonderful vet books which inspired a whole literary genre.

He inspired Peter, too. Encouraged by the success of James Herriot, he wrote a new gently humorous novel about the trials and tribulations of a rural Yorkshire policeman. Constable On The Hill, he called it.

It was snapped up by Robert Hale and published, using the pen name Nicholas Rhea, in 1979. The rest, as they say, is history.

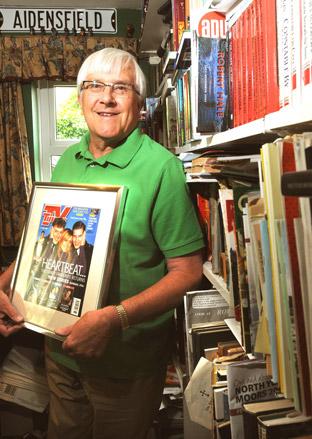

Thirty-five books later – he thinks it’s 35, Peter says, although he’s not entirely sure – the Constable books have come to an end, with the aptly titled Constable Over The Hill: a typical Peter Walker joke.

Once Heartbeat – the massively popular TV series inspired by his books – finished, it seemed natural to bring the books to an end, too, says the 75-year-old author, who looks wonderfully hale and hearty despite being diagnosed and treated for prostate cancer five years ago.

Except that – and fans will be thrilled to hear this – he isn’t bringing the books to an end, really.

Series one has finished, he says cheerfully, sitting in the south-facing conservatory of his home in Ampleforth looking out towards the Howardian Hills. Bur now he’s started work on series two… Keen to escape the sepia-toned 1960s setting of the original books, he has fast-forwarded the action 25 years or so. It is the 1980s – or possibly the early 1990s. “I’m a bit vague on that!” he admits. Constable Nick, the Yorkshire policeman who was the narrator and central character of all the Constable books, has retired.

He has also inherited some property smack bang in the middle of a Yorkshire abbey (yes, Peter admits, close observers might notice some similarities to a certain abbey in Ampleforth). The Abbot asks Nick for advice on security – with the result that Nick sets up a private abbey police force, along the lines of the York Minster police.

The result is Constable In The Cloisters. A draft of the book has already been sent to his publishers, and, hopefully, it will be the first of a whole new series of rural adventures. Fans of the original Constable books will be delighted to find a number of well-loved characters putting in an appearance – including Oscar Blaketon and Nick’s old policeman friend, Ventriss.

They are both getting on a bit, Peter admits. “Blaketon will be in his 70s, likewise Ventriss.” So there may be a touch of the Last Of The Summer Wine about their adventures – but of course written with Peter’s trademark warmth and gentle humour. Fans will lap them up.

It is 30 years since Peter retired from the police to concentrate on his writing – but he still has many fond memories.

As a young cadet in Whitby he frequently found himself with not much to do, he admits. He started learning to type. “I copied out huge chunks of Moriarty’s Police Law, the bible of the police force.”

His fellow police officers quickly cottoned on to the fact he could type, and so began to pester the young trainee to write up their reports for them. So he began typing up reports about accidents and minor local crimes: and found he loved it. “I decided I wanted to be a writer then, and I’ve been a writer ever since!” he says.

He began writing sketches, and in 1966, when he was the local bobby in Oswaldkirk, came second in a national police essay writing competition.

He also began doing radio broadcasts for BBC Leeds.

One day, he got summonsed to see the Chief Constable.

Peter hadn’t had his broadcasts approved, and panicked, thinking he was in trouble. The chief cleared his throat. “There was I, at seven o’clock in the morning, having my breakfast,” he told the young policeman. “And there was you, talking about sheep, on the radio!”

Peter chuckles again. “I said ‘yes, sorry sir!’” he recalls. “And he said ‘Bl**** good show! I’m looking for an instructor in our training school. Are you up for it?”

He was. He spent seven years as an instructor, then was promoted to inspector and put in charge of the police press office.

They may have been great at tackling crime, but his police colleagues weren’t always on the ball when it came to spotting what made a news story, Peter quickly learned.

On his first day in his new job, he went into the control room at police HQ to find out what was going on.

Not much, he was told. “There’s a motorcycle running up the A19 towards York with its panniers open and £5 notes flying out. But the Press won’t want to know about that.” Peter quickly put them right.

He was press officer at the time of the notorious Prudom murders and subsequent manhunt. One of his proudest moments was being able to persuade the press not to attend the funeral of Sgt David Winter, one of Prudom’s victims.

Crowds lined the streets of Malton that day to pay their respects, he recalls. But Sgt Winter’s widow had asked him to try to make sure there were no press actually at the graveside. Fortunately, he had built up a good relationship with the “gentlemen of the press” by then. He asked a reporter from The Sun if he would stay away. “And he said ‘tell us not to go, Peter.’”

He did, the Sun reporter passed it on, and not a single member of the press broke the ban. “I was quite proud,” he says.

The characters in Peter’s Constable books were based on people he met during his policing years – and especially in his time at Oswaldkirk.

Constable Nick wasn’t actually based on himself, he stresses. “Although you use your own experiences. But he was an amalgam of various bobbies.”

He himself grew up on the moors – in the centre of what was later to be Heartbeat country – and his fictional village of Aidensfield owes something to that, and something to his time as the beat bobby in Oswaldkirk.

And the name of his now-famous village? He’s a Roman Catholic, he says – and his church in Oswaldkirk was St Aidan’s (notice the different spelling). “There was a field opposite it… that’s the real Aidansfield.”

Just don’t try telling anyone in Goathland that…

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel