KEVAN Baker still remembers the moment his life changed forever. It was Easter 1979. He was a 19-year-old university student driving a group of friends from the Midlands to a holiday cottage in Thirsk. As they approached Sheffield on the M18 the driver of the Hillman Imp ahead fell asleep at the wheel.

“I swerved off the road,” Kevan, now 51, recalls. “We went off the motorway. There were no seat belts, no crash barriers, in those days.”

The next thing he remembers was being rushed by ambulance to hospital. “I was told I had broken my back, and was never going to walk again.”

It was a crushing blow. Until then, he’d been an athletic young man – a keen rugby player, who played for his school and for Lichfield, the Midlands town near the village where he grew up. He’d been in the second year of a degree in computer science – and his whole life had been ahead of him.

Suddenly, everything was different and he found himself thinking: “What am I going to do now?”

He’d always been resilient, however – whatever life throws at him, he says, his motto is “get on with it”. He resolved to do so. He was in hospital for a year: and during that time he decided he’d finish his degree.

Then one night two men came on to his ward in wheelchairs. “They were really sporty, muscly guys,” Kevin recalls. “I asked what they were doing, and they said training for the 1980 world disabled games in Arnhem, Holland.”

It was a revelation. 1980 wasn’t like today, Kevan said. There seemed little prospect of a decent career if you were in a wheelchair. “Businesses weren’t taking people in wheelchairs on.” But at least he could be involved in sports again.

Spinal units such as Pinderfields were strong on rehabilitation. And they helped recovering patients do a range of sports – even holding the British Wheelchair Sports National Games every year.

Kevan chose the discus. “I had done a bit of shot-put at school, so I thought I’d try that.”

By the time he left hospital, his coaches told him he had the potential to make the British disabled team. So he decided to find himself a coach.

He went back home to live with his parents, wrote to the dean of his university, who said he could return to college – and then went to a local athletics club at Cannock and asked about the discus.

The club had no facilities for disabled people. “The guy said ‘if you come along on Sunday morning we do a ‘have a go’ session over there in the corner,” Kevan recalls.

He replied that he wasn’t interested in “having a go in the corner”. “I said I was interested in doing it properly, getting into the British team.” He put the coach at Cannock in touch with experts at the British Wheelchair Sports Federation. “And he came back with a complete training plan.”

At the same time as he was finding a way back into sport, he was also struggling to find a career. He graduated in 1981 with a 2:1 in computer science. But companies weren’t interested in taking on someone in a wheelchair. He sent his CV off everywhere. “And I never got a single offer.”

Undaunted, he tried again – sending his CV back to the same places, but this time without mentioning he was paraplegic.

“Within a week, I got an offer of an interview for a junior programmer’s position with Allied Breweries in Burton-on-Trent.”

There was still the question of how he’d get into the Allied Breweries offices for his interview. “I rang the secretary and said ‘is the place where I’m being interviewed accessible?’. She said ‘what do you mean?’. I said ‘for a wheelchair?’ and she said ‘you’re never in a wheelchair!’” To her great credit however, she didn’t tell anyone that Kevan was disabled, and when the day came for his interview, she wheeled him in with a flurry.

“I was told later that I had got the job as soon as I was wheeled in!” he says. “They said ‘if you have the guts to do that, we want you.’”

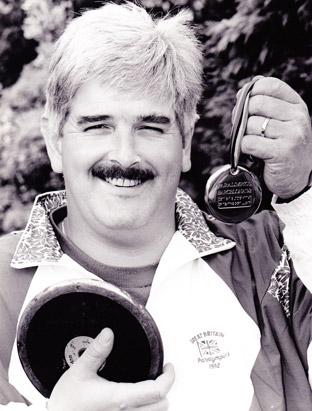

It was the start he needed. He moved to Sheffield, taking a job with Midland Bank, and later joined Aviva in York. His sporting career was also going well. In 1987 he broke the British wheelchair discus record, and he was selected for the British team for the 1988 Seoul Paralympics.

That was a breakthrough year for disabled sports, he says. Until then, nobody had really taken them seriously. That changed at Seoul. The Koreans, he said, had no idea how to host a Paralympics. So they staged them in the same way they’d staged the Olympics. Kevan, who’d never competed in front of more than 50 spectators, found himself with the rest of the British disabled team coming out in the Chamsil stadium in Seoul in front of 120,000. “We were treated like royalty.”

Kevan was placed fourth in Seoul. And between then and the 1992 Barcelona Paralympics there was huge development in disabled sports. Records tumbled – Kevan himself broke the discus world record twice – as disabled athletes finally found themselves being taken seriously.

Today it is accepted that the top disabled athletes really are elite sportspeople. That’s how it should be, Kevan says.

Which doesn’t mean disabled people who aren’t going to be able to make the British team shouldn’t take up sport. They need to keep fit and active in the same way as anybody else, he says.

That is one of the things the organisation he now chairs – WheelPower, formerly the British Wheelchair Sports Foundation – is keen to promote.

After winning two Paralympic bronzes, becoming World Champion three times, and holding the disabled discus world record four times Kevan, who is now Aviva’s York-based national community affairs manager, realised in the mid-1990s that his competition days were over. He moved into voluntary disabled sports administration instead.

In 1994, he became chairman of British Wheelchair Athletics then, in 1995, vice chairman of the British Wheelchair Sports Foundation, becoming chairman the following year. He is still chairman today – and it is for his contribution to disabled sport that he was made an OBE in the New Year Honours.

It is something he clearly still cares passionately about. There aren’t enough disabled athletes for disabled sports clubs all over the country to be viable, he admits.

Instead, WheelPower has experts who can advise able-bodied coaches at local sports clubs how to coach disabled athletes. So there shouldn’t be any barrier, these days, to someone who is disabled taking up sport.

He can’t resist a final plug. “If you’re in a wheelchair and fancy playing table tennis, say, get in touch with WheelPower,” he says. “They will give you the information you need, speak to your local coach, and advise you on what to do.”

• WheelPower can be contacted at wheelpower.org.uk or phone 01296 395995.

• Kevan Baker had just come out of hospital, where he was being treated for a skin condition related to his paraplegia, when a letter bearing the Cabinet Office crest arrived. His wife, Lynne, brought it up to him.

It asked if he would accept the OBE.

He was overwhelmed, he admits. The honour came when he was at a pretty low ebb, facing weeks of lying helpless in bed at home feeling guilty about not being able to go to work – Aviva have been great to him, he says. “And this gave me a real lift. I have won international gold medals, and been a world record holder, but getting this is right up there with them.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here