WHISPER it quietly but Neal Guppy, who last night became the latest in a long line of distinguished men and women to be granted the honorary freedom of York, once tried to escape the city in which he has become a legend.

True, he was only 17 at the time. He was lured, he says, by the prospects of an exciting new life in a big city – Bristol – and by dreams of becoming an aircraft engineer.

Actually, he wanted to be a Spitfire pilot – as did just about every other boy growing up after the war. Then, as a schoolboy living in Clifton Without, he became hooked on building model aeroplanes. He was walking along the street near his home one day when he saw an older boy with a model glider.

“He kept letting it fly in front of him, and I thought how beautiful it was,” he recalls, gesturing to indicate the glider’s graceful movement through the air. “It was the poetry of flight.”

Typical Neal Guppy, that. We are sitting in the bar of his Enterprise Club on Nunnery Lane. Two young members of his jive class – 23-year-old Patty Sachamitr, and Joseph Peach, 22 – are toasting themselves by the open coal fire. Upstairs, members of his classical music club, who range in age from 74 to 90, are listening to a selection of Spanish classical music he has chosen to warm them up this bitter winter day.

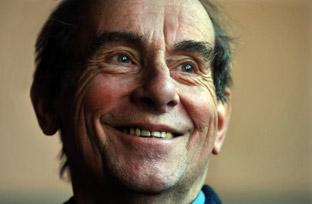

Neal, meanwhile, has been joshing around with Press photographer Nigel Holland, who’s come to take his photo. “With or without glasses?” Neal asks. Whichever, Nigel says, concentrating on his camera. Neal, who’s been boasting all afternoon about his new false teeth, pauses for just long enough. Then, “With or without teeth?” he asks.

He’s like that: irrepressibly teasing and jokey one moment, and then the next he comes out with something as memorable and beautiful as that line about the poetry of flight.

But back to the teenage Neal. The sight of that model aeroplane gliding through the air when he was a lad clearly left a deep impression. Before long he had started a model aircraft club – a sign of things to come – at Archbishop Holgate’s School. Soon he took to spending his Sundays flying his models at Clifton aerodrome.

It was all the rage in those days, he says. “You could get as many as 300 people at the aerodrome on a Sunday.”

Then came his getaway attempt. In the middle of doing his A-levels at Archbishop Holgate’s, he got itchy feet. The 17-year-old managed to land a much sought-after apprenticeship with the Bristol Aircraft Company – and off he went to live the dream. “It was a big city. I thought it would be exciting. I was going to be an aircraft engineer,” he says.

True to form, he immediately joined the BAC apprentices’ social club, held in a cellar, and became an active member. But he just didn’t take to life in Bristol. Yes, it was a big city – too big.

The people just weren’t as friendly as in York, somehow. “If you went shopping and saw someone you knew from work, they’d say hello, give you a brief smile, and then go on their way. In York you stop for a chatter, and before you know it you’re going to a bar or a coffee bar to continue the chatter.”

So, after just a few months, he came back home. “I felt ashamed of myself. People were coming from all over the world for those apprenticeships. But my heart wasn’t in it.”

Bristol’s loss was to be York’s gain, but before he could settle down and set up the legendary Enterprise Club, he had two years of Army national service to endure.

Endure is the right word. He hated Army life.

“It was the mindless discipline of it,” he says. “It taught me about what it must be like to live in a totalitarian country, and made me all the more aware of what our freedoms are.”

Army life taught him something else, too. “I learned how to skive,” he says. “That was something I could do with conviction.”

Army service over, he had to decide what to do with the rest of his life. Inspired by George Robinson, one of his teachers at school, he decided to go into teaching.

“He had so much enthusiasm. I thought if I could do something half as good as him, I would be useful.” He trained as a science teacher at St Johns, and then worked for several years at Derwent Secondary School.

But more and more, the young teacher found he had another draw on his time – the Enterprise Club.

He had always been an inveterate organiser of clubs and activities – ever since, as a boy of nine or ten, he staged an impromptu fair in his garden one day while his parents were out. He set up a game of hoopla and charged local children to play. “When my parents got back they were appalled and I had to give all the money back.”

While a student at St Johns, he’d joined the students union’s education committee, and started running dances on Saturday night. Then, while still at St John’s, he launched the Enterprise Club.

At first, it didn’t have its own home. It was 1961. Neal ran regular jive and dance nights at places such as the Clifton Cinema Ballroom, and in a room at the Woolpack in Stonebow. The aim, he says, was to provide “intelligent entertainment” for young people who weren’t at university.

The club was named by a vote of members at the Clifton Cinema. The two most popular names were the Stork Club and the Pudding Club, Neal recalls. Thankfully, he overrode those, and managed to go with the third preference, the Enterprise Club, instead.

The club quickly became hugely popular. Neal gave up teaching to devote himself to it full time, and in the mid-1960s, it moved into its first permanent base, at Dixon’s yard in Walmgate, where the cellar became famous as a venue for local bands.

In 1975, the club moved again – this time to Nunnery Lane. It is still there, still thriving to this day, hosting everything from regular WEA classes to classical music groups, dance classes to kung fu, meetings of the York War Games Society to creative writing groups.

In the nearly 50 years he’s been running the club, Neal has married and separated, had two children and survived cancer.

That struck nearly three years ago. Yet within two weeks of surgery, he was back sitting at the door to Guppy’s, taking money from members as they came in: and within a couple of months he was teaching his beloved jive again. His ex-wife, Kay, and his family helped him through, he says – as did all his friends and club regulars. Every week when they came in, they could see he was getting that little bit better.

“Their faces would light up on the way in. That was the best tonic I could have had.”

Now he’s been made an honorary freeman of York – the city’s top honour. He can’t believe it, he says. He’s spent his life doing something he loves – that was reward enough. “And now I’m being rewarded for being rewarded!” He gives that famous Guppy smile. “I am jammy!”

CHRIS Calvert was one of the early members of Guppy’s Enterprise Club. Now 64, and still playing in a band, back in the early 1960s he was a drummer with early rock bands such as The Scorpions and The Tycoons.

Those were the years of Ouse Beat, he recalls – York’s answer to Mersey Beat. There were something like 100 bands playing in the city and Neal Guppy was right at the heart of things, providing venues and even setting up a band agency to help young bands get gigs.

It’s the Walmgate club that Chris remembers best – the tiny cellar was Neal’s version of the Cavern Club, and there was great music there, Chris says.

But he also remembers jive parties at The Woolpack – and once playing a gig for Neal upstairs at Bettys, when some young men tried to gatecrash the evening.

“The lads from the club went down to stop them coming up, but this guy wouldn’t take no for an answer.” There was a fight, which resulted in Neal losing Bettys as a venue.

Such trouble was very rare at Guppy’s, though, Chris says. Neal was careful about who he allowed to become members. Guppy’s was an exclusive club and once you were allowed in, you didn’t want anything to spoil it. “Neal was a household name,” Chris recalls. “It was the place to go. Once you were in you felt great. People were really proud of being a member.”

Ian Gillies, left, the York councillor who nominated Neal for the freedom of the city, was also a club member in the early years. He recalls how when Neal took over the Walmgate premises, he persuaded his members to whitewash the basement for him. “He was creating his own Cavern. But he gave us free tickets to go in.”

The great thing about Neal is that he’s never been one to court favour or influence, Ian says. “He’s just got on with things and provided everyone with this great place to go.”

That’s the same today as it ever was.

Patty Sachamitr, 23, started going to Neal’s jive classes last year, after a colleague at the University of York suggested it. She’d always wanted to learn to dance, but the idea of classes had always seemed too intimidating.

Not Neal’s. “He’s fantastic!” she says. “He’s got so much energy, and he’s not intimidating at all. It’s a very friendly, relaxed atmosphere.” He doesn’t exactly teach jive, adds 22-year-old Joseph Peach, another member of the jive group – he just shows you the basic moves then encourages you to get on with it. “But I’ve met so many people here. It’s a great place to come.”

What is means to be an Honorary Freeman...

AS AN Honorary Freeman of the City of York, Neal Guppy joins a select group which includes The Duke of Wellington, Sir Winston Churchill, John Barry, Dame Judi Dench, Professor Sir Ron Cooke and, most recently, Peter Gibson, the man who saved the Rose Window after the Minster fire.

The Honorary Freedom remains the most important honour the city can bestow. There are three grounds on it can be can be conferred. It can be given to those who are loyal servants of the city; to distinguished people; and to Royalty.

Neal Guppy certainly meets two of those criteria – and to those who were teenagers in the 1960s he comes close on the third, as well.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel