MUCH has been written - and quite rightly - about the men who died on the beaches of Normandy on D-Day.

But what about those who were killed in action far from the coast of France?

On that fateful June 6, 1944, Trooper Gordon Adams was serving with a tank regiment, the 17/21 Lancers, that was pushing northwards through the Italian peninsula.

The unit had already seen action in North Africa, before crossing the Mediterranean to join in the invasion of Sicily and then Italy.

They faced fierce opposition as they fought their way northwards through German-occupied Italy, as revealed by an entry in the Lancers' War Diary by Major General V Evelegh, Commander of 6 Armoured Division.

"We have advanced over 215 miles by road from Cassino to Perugia, have fought many battles, overcome countless demolitions and endured heavy shelling and mortaring," he wrote.

By June 6, the Lancers had reached an area north east of Rome. There, they ran into organised opposition near the village of Monterotondo.

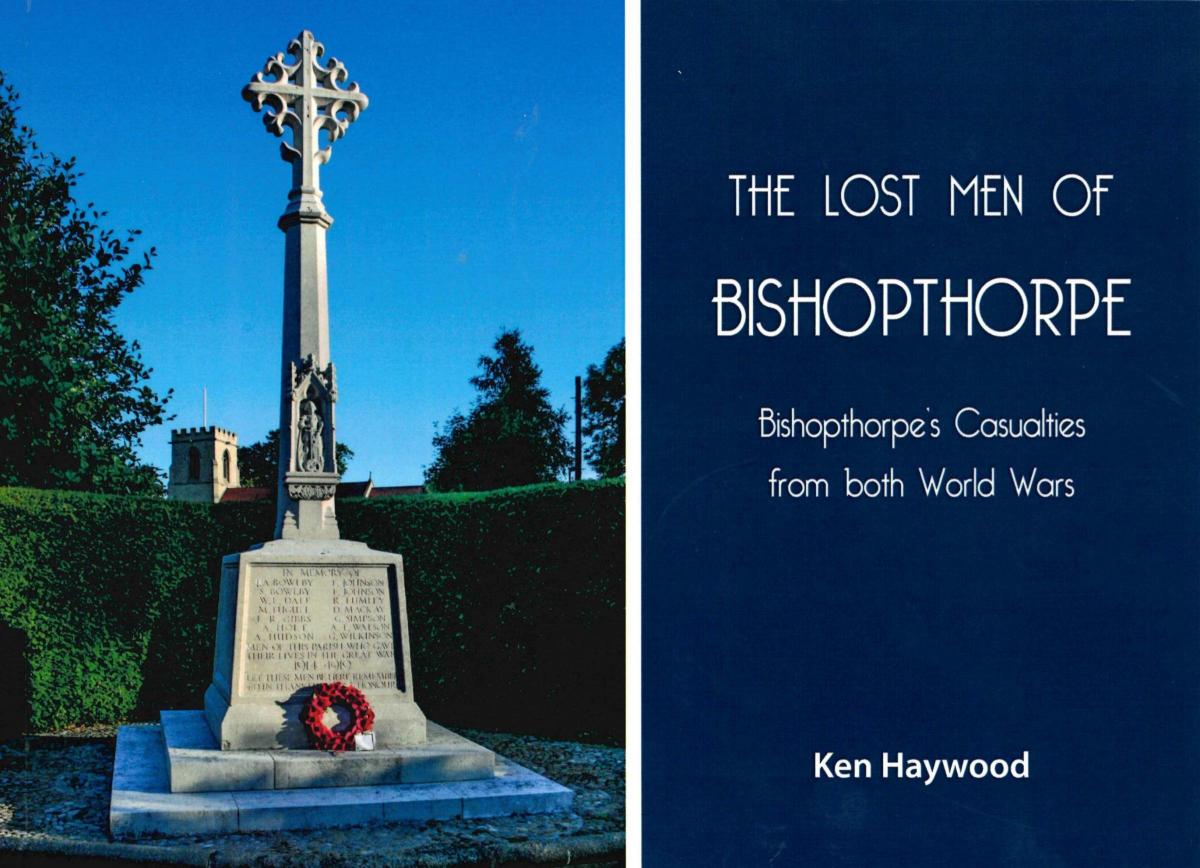

"This was the first serious clash with the enemy for several days," writes Ken Haywood, in his new book The Lost Men of Bishopthorpe.

Serious is the word. It took three days to dislodge the German forces, by which time two of the Lancers had been killed, and another three wounded.

Among the dead was Trooper Adams, apparently killed while loading shells into his tank. He was 22.

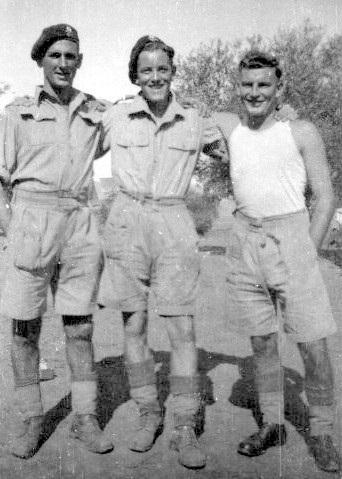

A photo in Ken's book shows a friendly, open-faced young man holding a kitten. In another photograph he is seen in uniform, browned by the desert sun and with his arms around two comrades.

Gordon had been born in Bishopthorpe in late 1921, the son of William Adams and his wife Marjorie. Like so many of the young men who died in the two world wars, he had been full of youthful promise.

He went first to Bishopthorpe School then, on a scholarship, to Archbishop Holgate's Grammar School. After leaving school, he went to St Luke's College, Exeter, to train as a teacher.

Then the war intervened. In April 1943 he joined the 17/21 Lancers in North Africa, where they served under Montgomery. Just over a year later, he was dead.

Gordon's mother, Marjorie, had lost her brother, Frank Johnson, in the First World War. What she must have felt when she lost her son, too, a generation later, doesn't bear thinking about.

Gordon is one of 11 Bishopthorpe men who died in the Second World War who are featured in Ken Haywood's book. Ten are commemorated on the village's war memorial. One of them - Private Charley Johnson, who died a year after the war ended of blood poisoning which resulted from tuberculosis contracted during the war - is not.

With the help of war records and information and photographs supplied by families, Ken has pieced their life stories together for his book.

Last week, we looked at the lives of some of the Bishopthorpe men who died in the First World War featured in Ken's book. This week, we remember a few of those who died a generation later, in the Second World War...

- The Lost Men of Bishopthorpe: Bishopthorpe’s Casualties from Both World Wars by Ken Haywood was published by K&L Publishing on November 8, priced £10. It is available from York Explore libraries or direct from the author at kandlpublishing@yahoo.com for £10 plus p&p. Any profits will go to the War Memorials Trust

Meet some of the Bishopthorpe men 'lost' in the Second World War

Granville Hebdon

Granville was born in Pontefract in 1922, the son of William and Lily Hebdon. It was only later that the family moved to Bishopthorpe. Granville then finished his education at Nunthorpe Grammar School, before getting a job at Rowntree's.

When war was declared, he joined the Royal Navy as an ordinary signalman, and was posted to HMS Tynedale, a Type 1 Hunt class Escort Destroyer.

The Tynedale saw action throughout the early years of the war - including taking part in 1942 in a daring raid designed to put the French harbour of St Nazaire out of action for the Germans.

By 1943, the Tynedale was on escort duty in the Mediterranean. There, on December 12, she was spotted by a German U-boat, which fired a sophisticated acoustic torpedo which could home in on the sound made by a ship's propellers. The torpedo hit the Tynedale amidships, splitting her in two. The ship's bow section sank quickly, but the stern remained afloat for some time, allowing the survivors clustered there to be rescued.

Granville wasn't one of them. His official records describe him as 'lost at sea' - one of 65 men from the Tynedale to have shared that fate. He was 21.

John Dixon

John Dixon was born in York in January 1913. The Dixons lived in Malton Road, but after he married Amy Ward in September 1939 John and his wife came to live in Sim Balk Lane, Bishopthorpe.

He joined the merchant navy as a radio operator in January 1940. He seems to have made several voyages, but on the night of November 22/23 1940 he was serving as second radio officer on board the SS Oakcrest, an ageing tramp steamer which was part of a convoy of 43 ships crossing the Atlantic for North America. On the night of November 22, when the convoy was several hundred miles west of Scotland, two U-boats began shadowing the ships. Early on the morning of the 23 the Oakcrest was hit by a torpedo, sinking in just a few minutes.

John Dixon was one of 24 crewmen who managed to scramble into a lifeboat - the other 17 went down with the ship. The survivors thought that when daylight came their boat would be spotted and they would be picked up - but for some reason that didn't happen. The open boat, which had little food or water, drifted for several days. During this time, ten men died and were buried at sea - among them John Dixon. There is a handwritten note in his Merchant Navy records which reads: 'Died from exposure between November 22 and 30'. He was 27.

Survivors in the lifeboat eventually managed to rig a makeshift sail and headed east for nine days, eventually coming ashore on the Island of Barra in the Outer Hebrides. Just six men survived.

Edgar Umpleby

Edgar was born in Scarborough in December 1918. But his father Ernest took the lease of Garth Farm in Acaster Malbis. The family moved there, and Edgar completed his schooling at Bishopthorpe School, leaving in 1932.

At the outbreak of the war he joined the RAF, rising to become a leading aircraftman. He was posted to an airbase north of Singapore on the Malayan peninsula, and after the fall of Singapore was evacuated to Java where, along with other men of his unit, he was captured by the Japanese on March 8, 1942.

His story proved very difficult to write, Ken Haywood acknowledges, because of the 'lack of any significant information regarding many of the men who died in the Far east during the war'. However, it seems he was taken back to Singapore by the Japanese then, along with 838 other prisoners of war from the UK, to Kota Kinabalu in north Borneo. Six months later, the prisoners were moved to Sandakan camp, also in Borneo, where they joined 1,500 Australian prisoners of war constructing an airstrip for the Japanese. "The work was hard and unrelenting," Ken writes. "Food was scarce and the discipline was brutal. There were no significant medical facilities. Using only hand tools, the men were tasked with levelling a white coral reef for the airstrip. Some went blind from the glare of the coral in the blazing sunshine."

Despite this, many of the men survived into 1944. Towards the end of the war, however, when it became clear the tide was turning against the Japanese, there seems to have been a 'general policy of ensuring that no prisoners were to be allowed to be freed', Ken writes. "It is thought the intention behind such a policy was an attempt to limit the number of possible witnesses to war crimes."

Food rations were withdrawn, and many prisoners were sent on 'death marches' into the jungle from which they never returned. Edgar was at least spared that. According to records, he died of malaria on or about March 20, 1945 - though we only know that from Japanese reports, Ken points out. Edgar was 26.

Ted Whittaker

Ted was the last man from Bishopthorpe to be killed in action in the Second World War. The son of William and Mary Whittaker, he was born in York in 1924. The family moved to Bishopthorpe when he was six. After leaving school, the young Ted got a job with a firm of local estate agents, Richardson and Trotter. He was highly regarded. "I have had a good few boys through my hands, but none more likeable," read a letter from his employers. "He was a true broth of a boy, and just as solid in his character as in his splendid frame..."

In 1942, when he turned 18, Ted volunteered for the RAF. He became an air gunner and, in 1944, joined 223 Squadron, a unit of B24 'Liberator' bombers based in Norfolk. On the night of February 20/21 1945 his plane was shot down by German night fighters while on a mission to bomb Dortmund. Ron Johnson, the plane's navigator, was one of several crew members who parachuted to safety. They were captured by the Germans but survived, and Ron was later to write an account of what happened.

"He last saw Ted Whittaker buckling on his parachute by the escape hatch," Ken writes. Ted never made it - though it wasn't until nine months later that his family were officially informed that he had been killed in action. He was 21.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here