THE English Civil War was a bitter clash between King and Parliament in which nearly nearly five percent of England's population was wiped out.

Battles such as Marston Moor - on which the fate of York and of the north hinged - left deep scars in the nation's psyche. And the uneasy peace that followed the ending of hostilities in 1651 left a different kind of legacy: chilling tales of ghostly presences on the battlefields.

Marston Moor recreated: A volley of Musketfire is aimed into opposing ranks at a re-enactment of the Battle of Marston Moor. Picture Matt Clark

Researcher Imogen Peck has been delving into the archives to look for contemporary accounts of supernatural goings-on ahead of a two-day conference at the National Civil War Centre in Newark which opens tomorrow (August 7).

And she found that Yorkshire and the north seem to have generated more than their fair share of supernatural tales in the wake of the war.

These were reported in the London-based news sheets of the day with an almost ghoulish relish, she says.

"Perhaps the north being a long way away seemed somehow more magical and prone to such portents. But they were treated with great seriousness."One pamphlet published in London in 1659 reported on 'The five strange wonders in the north and west of England' - ghostly appearances reportedly connected to recent Civil War battlefields.

One of these was an “Exhaliaton in the Air” sighted over Marston Moor, with two fiery pillars visible at noon and glimpsed as far away as Doncaster and Halifax. Between them “intervened several armed Troops and Companies in Battail array” who exchanged volleys. The Northern army vanquished that of the South.

“What this portends no man can conjecture aright” the writer of the piece said - before going on to speculate anyway, in what amounts to a wonderful piece of 17th century political spin. The two pillars represented Parliament and his Highness "subduing popish and foreign confederates" and calling on people to unite, he said.

Oliver Cromwell at the Battle of Marston Moor

The piece was written shortly after the death of the Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell. “And it's a pretty clear call to get behind the new Lord Protector Richard Cromwell at a time of profound uncertainty following the death of Oliver,” explains Imogen - using a bit of anti-foreigner feeling to unite everyone back home. That would never happen today.

Imogen cites another example of supernatural goings-on up north which was reported in London - and which was clearly anti-republican in sentiment. The February 1650 edition of the Royalist newsbook The Man in the Moon interpreted the appearance of soldiers in the sky as a warning of God’s discontent and a harbinger that war was on its way, she said. It stated that "In the North are still heard in the night, clatterings of Armour, neying of Horses, discharging of Ordnance, cryings and shreekings in the Aire, that much affrightneth the Inhabitants, frighting their Cattell some nights 3 or 4 miles from their Pastures: These are strange Predictions, and questionlesse the Warning pieces from heaven to prepare us against ensuing Warres and Evills that hang over our heads".

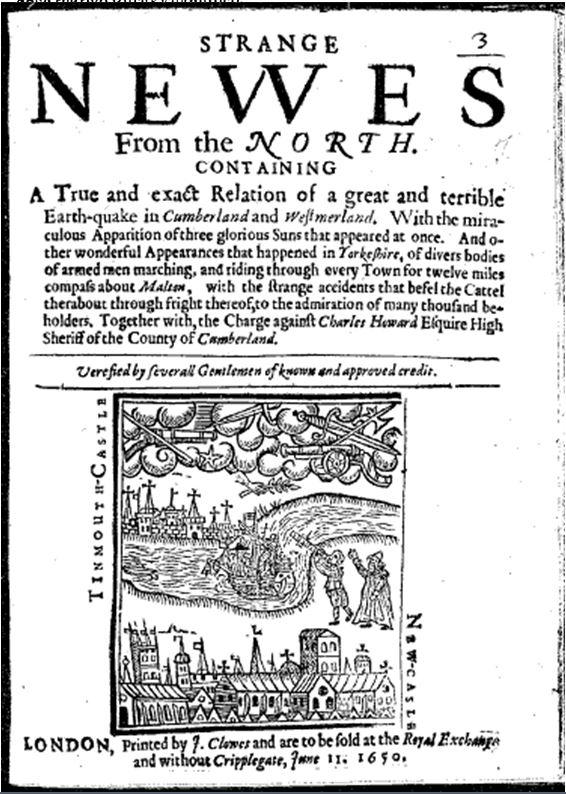

Strange Newes From The North

The same year another sensational report was published entitled “Strange Newes from the North”. It revealed an earthquake had struck Cumberland and Westmorland and three suns had appeared in the sky. Meanwhile in Yorkshire, the Newes reported, the bodies of armed men were said to have been seen riding and marching through several towns for twelve miles around Malton. Cattle suffered strange accidents through fright 'to the admiration of many thousand beholders'. These startling accounts had been vouched for by 'several gentlemen of known and approved credits,' the report claimed.

“We should not be surprised that people took such reports seriously, but the political interpretations are sometimes laid on pretty thick,” says Imogen. “There is a vast amount of material still be to be properly researched covering the rest of country.”

Imogen will be talking at a two day conference open to public at the National Civil War Centre in Newark on 7 and 8 August.

The conference will also spotlight little known aspects of England's costliest war - including battlefield medicine, welfare for maimed ex-servicemen and their families and the terrible plight of Irish refugees.

To find out more, visit www.nationalcivilwarcentre.com/events

York's part in the Civil War

York, a Royalist stronghold in the north of England, played an important part in the Civil War.

In April 1644 the city came under severe pressure from Parliamentary forces.

A Parliamentary army led by Lord Fairfax had inflicted a heavy defeat on Royalist forces from York at Selby on April 11. The Royalist commander was captured and as many as two-thirds of the 3,000 strong army were killed or captured, according to the History of York website.

Within days, Parliamentary and Scottish armies were encamped less than a mile from York’s walls on both sides of the Ouse.

The Royalist forces inside the city had built an elaborate system of trenches, shelters and towers outside the city walls which at first allowed the garrison to continue tending livestock in outlying fields and bringing in provisions.

But on June 3 the Earl of Manchester brought his Parliamentarian forces to join the siege. They took up a position to the north of the city, making a bridge by tying boats together so his army and that of the Scots were linked together.

The Parliamentarians built a battery of guns on Lamel Hill to bombard the city defences. A second battery was created at St Lawrence’s churchyard, not far from Walmgate Bar. Cannons pounded the area and reached as far as St Sampson’s Church in the city centre.

On June 8, the defenders were forced to withdraw inside the walls and set fire to the suburbs in the east.

A Royalist army under the command of the flamboyant Prince Rupert - the nephew of King Charles 1 - came to the relief of York.

The Battle of Marston Moor

But on July 2, Rupert rode out to meet Parliament and their Scottish allies at Marston Moor. The battle - possibly the largest ever fought on English soil - saw 42,000 combatants face each other with the first shots being fired at around 7pm on 2 July, 1644. The Royalist cavalry quickly made progress on one flank but was routed on the other by Cromwell's Ironsides, who swung in behind their foe, the national Civil War Centre says. By 10pm it was all over, with perhaps up to 5,000 killed, the vast majority of them Royalist cavaliers.

Rupert had effectively lost York - and the north of England - for the Royalist cause.

On July 16, 1644, the Royalists surrendered York. But thanks to the influence of Sir Thomas Fairfax, head of Parliament's New Model Army, and his father Lord Fairfax (both local men) the city was preserved from destruction and the Minster's world famous stained glass windows protected.

The National Civil War Centre

The National Civil War Centre, Newark

Housed in the magnificently restored Old Magnus Building - which dates to 1529 - the National Civil War Centre in Newark, Nottinghamshire, is the first of its kind in the UK, recounting the epic clash between King and Parliament. The bloody conflict spread across all parts of the British Isles, starting in Scotland and ending in Ireland. The death toll was terrible, yet much of our modern society is shaped by this compelling period.

The centre combines previously unseen artefacts, interactive technology – including a ground-breaking town trail app for smart devices - and a priceless treasure trove of information gleaned from documents which miraculously survived the tumult. We know, for example, how much it cost to have a Newark doctor examine a plague victim and how one poor women pleaded to be rehoused after her house was blown up by a grenado.

The centre is open daily 10am to 5pm. For more information visit www.nationalcivilwarcentre.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article