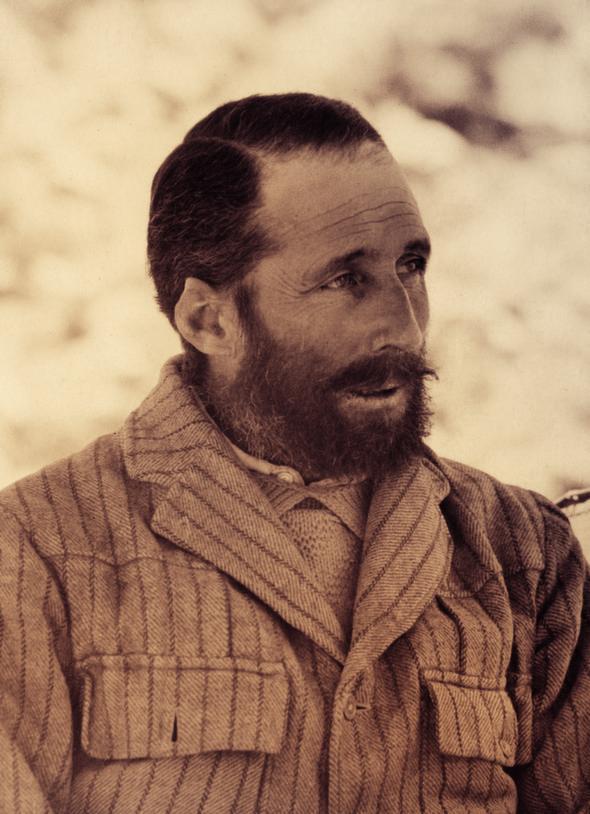

York academic Christopher Norton’s grandfather Edward was one of the great early mountaineers – the leader of the 1924 Everest expedition in which Mallory and Irvine died. Now his diaries and sketchbooks have been published for the first time. STEPHEN LEWIS reports.

AT 6.40am on June 4, 1924, two mountaineers set out for the final push of their attempt to climb the world’s highest mountain.

Howard Somervell and Edward ‘Teddy’ Norton had camped overnight in a small tent pitched precariously 26,800 feet above sea-level on Everest’s North East Ridge. They were just over 2,000 feet from the summit and climbing without the help of oxygen.

The weather that morning was brilliantly fine and calm, but bitterly cold: so cold, Norton confided later to his diary, that “one shivered continually despite layers of windproof clothing, & when in sun”. The pair had a meagre breakfast, boiling snow for water, then struck out diagonally across a yellow ridge high on the mountain’s shoulder, towards the final pyramid of rock that was Everest’s peak.

Somervell was suffering badly from a severe high-altitude cough and sore throat. At about midday, unable to continue, he had to give up. Norton carried on alone, while Somervell took a famous photograph of him pressing on up the mountain’s flank, his tiny figure dwarfed by the looming bulk of Everest ahead.

It was tough going.

“No footholds on sloping slabs,” Norton wrote later, “& much snow lying soft & powdery on these slabs.”

Exhausted, he managed to climb only another 100 feet or so. Then, at 1pm, the highest man in the world – the highest man there had ever been – turned back. He had reached a height of 28,128 feet, without oxygen, a record that was to stand for half a century.

He rejoined Somervell, and the pair scrambled back down to their overnight camp – and then down further, to Camp V, the point where they’d camped the night before at 25,500 feet.

It was sunset by now, and the going was treacherous: but the pair were keen to reach their colleagues, camped another 1,500 feet below them at Camp IV. They glissaded down the snow, but the exhausted Somervell dropped behind. Norton waited for him and then took his tent pole to lighten his load.

Eventually, three colleagues – George Mallory, Andrew Irvine and Noel Odell – came up to meet them with oxygen. They “escorted us back to IV (9.30), fed & looked after us royally,” Norton wrote later in his diary, with typical understatement.

It had been a remarkable attempt to scale the world’s highest peak without oxygen – one that resulted in failure perhaps, but also a record which stood for more than half a century.

It isn’t for Norton and Somervell that that 1924 expedition is principally remembered, however.

Within half an hour of arriving back at Camp IV Norton, a British Army Lieutenant Colonel who was the expedition’s leader, was struck down with snow blindness. It was an excruciatingly painful condition that was to leave him ‘stone blind’ for 60 hours.

When Mallory and Irvine set out from Camp IV at 7.30 the next morning for their own attempt to conquer Everest – this time with the aid of oxygen – Norton wasn’t able to watch them go.

“He crawled out of his tent to speak to their porters, because Mallory and Irvine couldn’t speak the language, but he literally couldn’t ‘see’ them off,” says Norton’s grandson Christopher Norton, a professor of medieval art and architecture at the University of York.

Norton was never to see Mallory and Irvine again. Still blind, he was carried down to Camp III, at a mere 24,000 feet above sea-level. He resolved to remain there until Mallory and Irvine returned.

For the following two days, members of the expedition trained their telescopes on Everest’s higher flanks, looking for signs of the climbers. Noel Odell, who had joined the pair in a climb up to 27,000 feet to study geology and who was the last person to see them - ‘going strong’ near the foot of the pyramid that was Everest’s peak – was spotted coming back down.

But by June 9 – a “rough, cold day, very stormy high wind on mountain”, as Norton recorded – there was still no sign of Mallory and Irvine. Norton sent a group up to search for the pair, with instructions to go no higher than 27,000 feet. But he confided his fears to his diary that night: “By now it appears almost inevitable that disaster has overtaken poor gallant Mallory & Irvine – 10 to 1 they have ‘fallen off’ high up.”

The pair were never seen alive again. In fact, no trace of them was found until 1999, when Mallory’s frozen body was discovered at 26,760 feet on the mountain’s north face.

How they died and whether they reached the summit of Everest first has long remained a mystery.

As expedition leader, it fell to Norton to write to Mallory’s wife Ruth and Irvine’s father to offer his condolences.

He was generous in his praise of the men. To Ruth Mallory he wrote: “You can’t share a 16lb high altitude tent for days and weeks with a man under conditions of some hardship without getting to know his innermost soul and I think I know almost as you do what his was made of - pure gold.”

He offered his own thoughts on what led to the two men’s death. “Everything points to the probability of... a slip by one or the other – a purely mountaineering accident.”

And he speculated as to whether they had, indeed, reached the mountain’s top. That must “always remain a mystery: I put it at an even money chance”.

Norton never made another attempt on Everest. He preferred climbing in the Alps, where the family had a chalet – and anyway regarded himself primarily as a professional army officer, not a mountaineer, says his grandson Christopher.

He died in 1954 at the age of 70, having reached the rank before he retired of Lieutenant General in the Royal Horse Artillery.

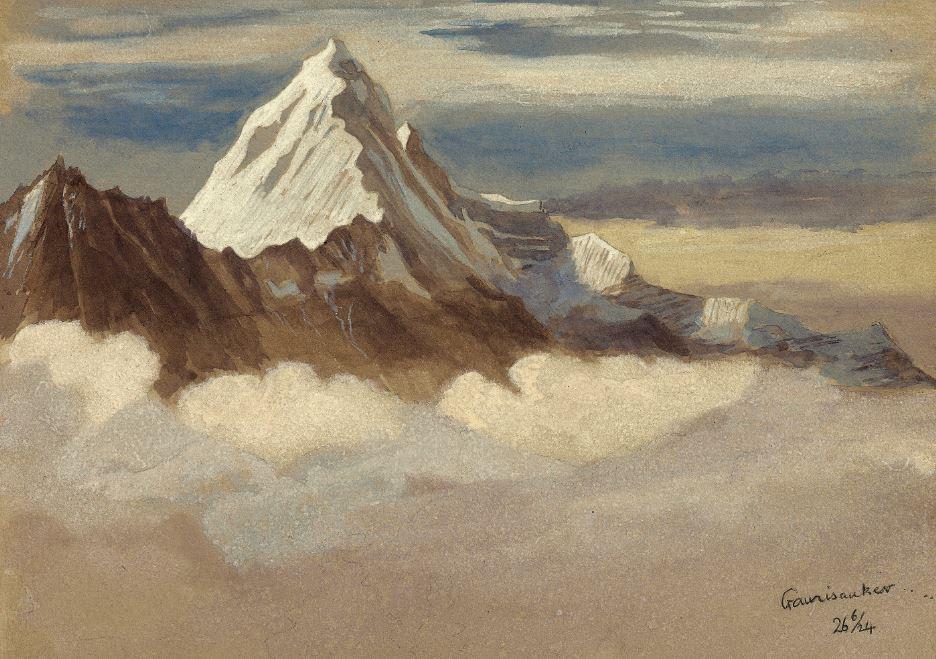

He’d taken part in two Everest expeditions: the one he led, in 1924, and another a couple of years earlier in 1922. On both, he set world altitude records for climbing without oxygen. A gifted amateur naturalist and painter with a vivid if spare style of writing, he also did something else on those two expeditions: he kept a diary and sketchbook.

He was always reluctant to show them to anyone, insisting they were of interest to no-one but himself.

But now his grandson has put them together in book form – together with an introduction and linking text – to provide a lasting memorial to the early Everest explorers.

It is difficult for us today to grasp just how remote and mysterious the Himalayas were to European explorers back in the 1920s, says Christopher, who lives off The Mount in York.

In 1921, when a reconnaissance mission set off to find the way to Everest a year before his grandfather’s first expedition, no European even knew how to get to the mountain, he says.

“They knew it was there, because they had seen it from India. But Nepal was closed. So they knew it was there, but nobody knew how to get to it.”

Because Nepal was closed, even to get within striking distance of the mountain meant journeying, on foot or on horseback, for four to five weeks from Darjeeling and across the Tibetan plateau.

Except when he wasn’t actually engaged in an attempt on the summit, Norton sketched copiously, making a record of the landscapes, the people, the places and the wild plants and animals he encountered.

Together with numerous black and white photographs taken by other expedition members (Norton didn’t carry a camera), they provide an extraordinary glimpse into a hidden world that was once as mysterious to Europeans as the dark side of the moon.

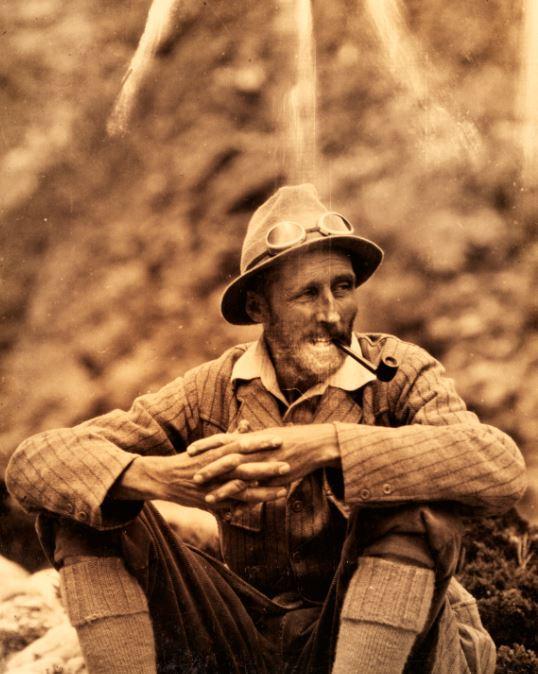

Christopher’s favourite photograph was taken on April 24, 1924, in the Tibetan community of Shekar Dzong, 40 miles as the crow flies from Everest itself. It shows Mallory, poignantly young and slender, standing next to Norton amidst a group of Tibetan dignitaries – among them the ‘Dzong pen’ or local governor.

It is an extraordinary photograph, Norton looking relaxed and cheerful, Mallory gazing off camera slightly as if momentarily distracted, the Dzong pen and his colleagues self-consciously posing.

Six weeks later, Mallory was dead, his body not to be discovered for a further 75 years. But he lives on in that photograph. And he lives on, with all his fellow explorers from those long-ago days, in this marvellous book.

• Everest Revealed: The Private Diaries and Sketches of Edward Norton, edited by Christopher Norton, is published by The History Press, priced £20

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here