HISTORIC Walmgate Bar is finally to get the repairs it badly needs after being hit by a car four years ago.

The £100,000 restoration project, due to start next month, will include support for the damaged wooden Tudor extension on the inner side of the Bar, which dates back to 1580.

There will also be repair works to the roof, balustrade and windows, as well as a new viewing platform on the top.

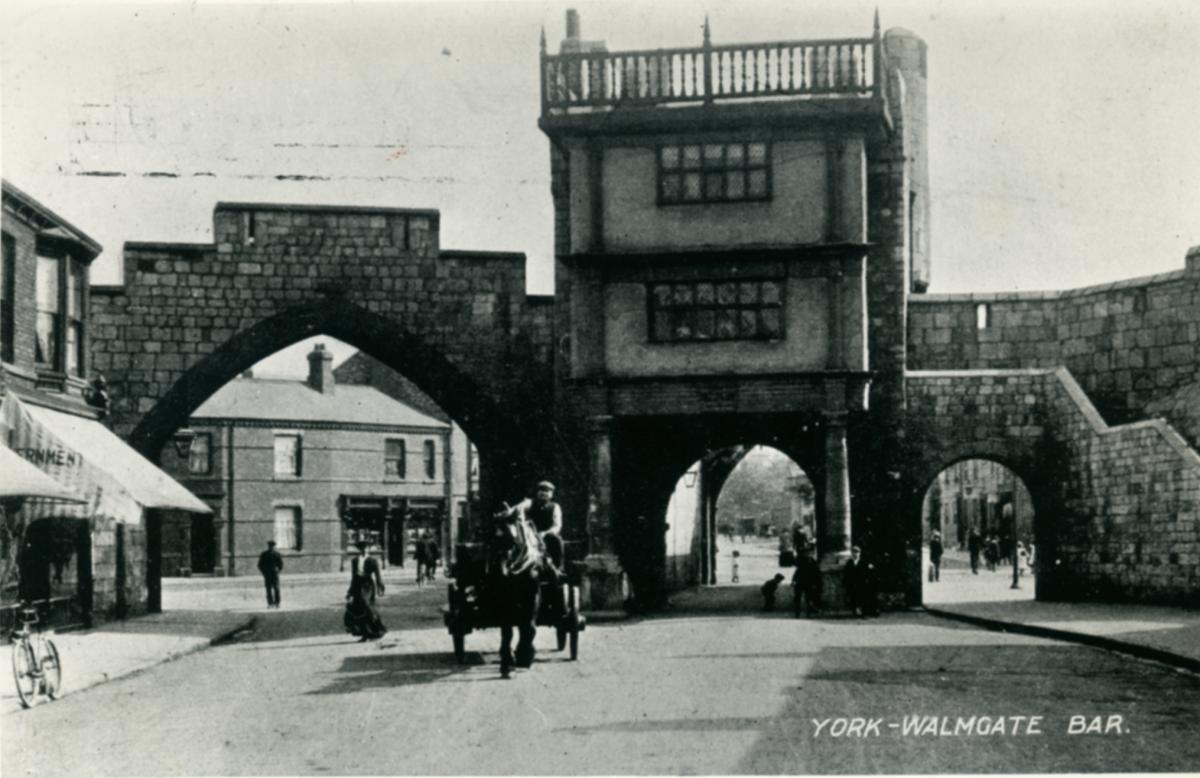

The Bar is the most complete of York's four medieval gateways - the only one still to have its barbican, portcullis and wooden inner doors.

It has stood guard at the south east corner of the city for almost 1000 years. And while in recent years the greatest threat to the medieval gate has come from vehicles crashing into it - or, before the central arch was closed to all but bicycles a few years ago, buses and lorries actually getting stuck inside it - it has, down the centuries, weathered much greater threats.

In 1489 it was burned (along with Fishergate Bar) by rebels protesting about taxes; in 1644 it was bombarded by cannon fire during the Civil War Siege of York; and in 1831 the famous barbican was almost demolished - being saved only by public pressure.

The inner stone gateway dates back to about 1100 or 1125, according to city archaeologist John Oxley - so it is a good 150 years older than most of York's stone bar walls. The barbican itself dates from the 1300s, and the wooden gates from the 1400s.

Throughout medieval times, a watchkeeper was based at the Bar, who would have checked visitors coming into the city. Normally, he would have lived in the house that was built into the Bar - although there is evidence that at times the house was rented out. Records show that in 1376, it was being let out for an annual rent of 10 shillings - possibly at that time the watchkeeper had his own house, Mr Oxley says.

Traitors' heads were displayed from Walmgate Bar in medieval times, as they were at other York bars. Volume 2 of 'An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York', available at British History Online, records how in 1469, "the head and banner of Robert Hillyard (Hob of Holderness) were displayed above the gate". Robert (or Hob) seems to have been the leader of a rebellion that may have been in part a protest at an ancient tax in northern England levied by St Leonard's Hospital.

Twenty years later, in 1489, the Bar was badly burned by rioters, who again seem to have been protesting about taxes. "But nothing is known of the extent of the damage," the Inventory of the Historical Monuments of York notes.

The Bar's most serious test came in 1644, when Parliamentary forces were besieging the city.

It was bombarded by cannon from Lamel Hill and St Lawrence's churchyard. Two cannon were then put in the street near the Bar, and another a 'stone's throw' away, the Inventory records. The Parliamentary army also began to dig two mines, with the aim of tunnelling under the Bar and blowing it up from underneath. But they were foiled by the defenders. "The Royalists dug a counter-tunnel, and flooded the mines that the Parliamentarians had been building," John Oxley says.

It didn't save the city: York surrendered to the Parliamentarians on July 16, 1644. Walmgate Bar had been badly damaged, but by 1648 had been repaired.

Copyright: York Museums Trust

Almost 200 years later, in 1836, unexploded Civil War mortar shells were found while workmen were working on a nearby drain, according to the Inventory of the Historical Monuments of York. By this time, the Bar had fallen into neglect.

It had survived a recommendation by the York estates Committee in 1831 for the barbican to be demolished, however. And in 1840, the Bar was fully restored by the York Corporation.

By Victorian times, Walmgate had become a notorious slum, one at the bottom of the social scale in York, notes British History Online. Its population "had been swollen by the Irish, whose numbers, though falling, continued to be considerable by the end of the century."

A letter to the York Herald in January 1870 gives a good idea of what the area was like. It describes "a number of men and women" standing nearby, "making remarks upon passer-bys, obstructing the footpath and indulging in the most obscene and filthy language even on a sabbath day." Such a thing would never happen in York today, of course.

Within living memory, many York people of a certain age still remember the cattle market on Paragon Street. It was there from 1827 until the mid 1970s - and the pens stretched right up to the barbican of Walmgate Bar.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here