For a few days a North Yorkshire church can be seen in a different light. MATT CLARK discovers why and learns its extraordinary history.

IT WAS used by wartime pilots as a navigation aid, now the spire at All Saint's Church in Newton on Ouse is a focal point once more with LED lights adding autumn cheer to the already too lengthy nights in celebration of All Saints Day.

The spire is also a familiar sight to rail travellers and anyone taking the night train north from York over the next few days will have a spectacular view of the structure as it is alternately bathed in blue, green and purple.

The show uses lights originally donated by Michael Brookesbank of Chauvet Lighting which are installed by Neil Peers, who runs Ahten EDS, bespoke electronics design services, based in Newton.

"They use LED technology and are remotely controlled via wireless from my office," says Neil. "All the primary colours will be seen and then various mixtures, the pink and purple I think look especially good."

Not that All Saints needs a helping hand to look its best. This fine church looks older, but was mostly rebuilt during the 19th century.

Actually, make that rebuilt twice during the 19th century. First in 1838, then again ten years later by George Townsend Andrews for the Hon Lydia Dawnay of Beningbrough Hall.

No one really knows why. Some believe a fire caused the church to fall into disrepair, but it could just as easily have been a simple whim of fashion.

Since the 18th century aristocrats added gothic follies to the estates of their Palladian style houses and in 1749 Horace Walpole even built a house with towers, battlements, arched windows and stained glass.

But by 1847 the Gothic Revival had become popular at large. Charles Barry's Lords Chamber had been completed at the new Palace of Westminster and that helped bring to popular acclaim Augustus Pugin's Contrasts: a polemic against industrial society that argued for a revival of medieval architecture, and a return to the faith and social structures of the Middle Ages.

It could be that Miss Dawnay, wishing to prove herself well read and thoroughly acquainted with modern trends, did so by heeding Pugin's plea at her own church.

And she certainly had the money to do it.

"I think the family weren't happy and wanted something better looking," says churchwarden David Theakston. "They had commissioned the Holy Evangelist Church in Shipton and felt their village church had to be more prominent."

So Andrews produced a Gothic design, including a 150-ft spire that could be seen from Brimham Rocks, 20 miles away. Symbolically it also proclaimed power with reminiscence of a spear point, giving the impression of strength.

Newton's spire also hides a secret, being built on top of a much older tower, which forms the only remaining part of the original Norman structure.

Not that you can easily tell, because All Saints turns out to be remarkable example of Gothic Revival and features work by some of the movement's biggest names.

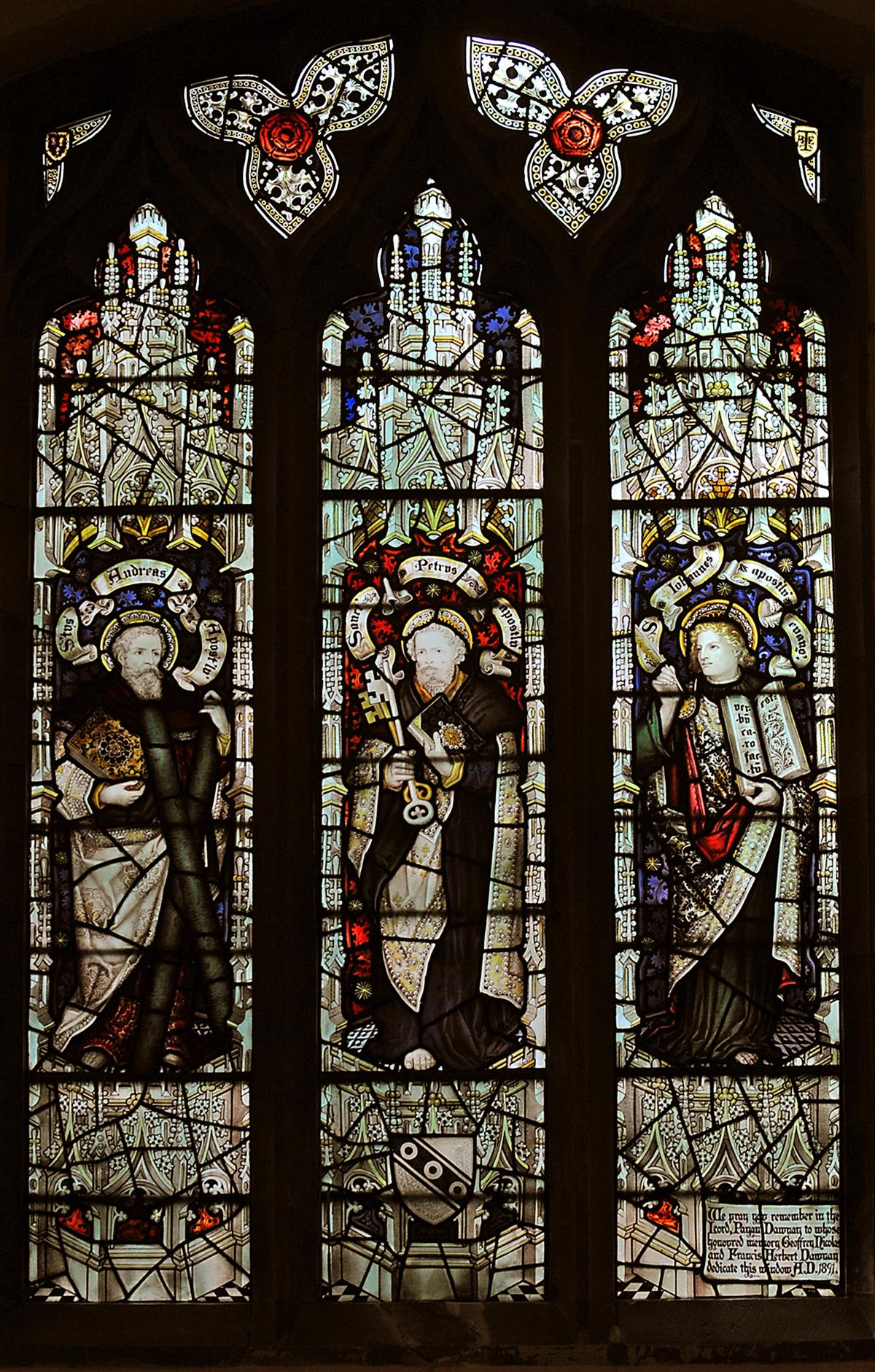

Take the east window by Thomas Willement, the pioneering 19th century artist who experimented with medieval techniques and became artist in stained glass to Queen Victoria.

Not to be outdone, Charles Kempe, who worked in the early Renaissance style and formed some of the finest Victorian stained glass, produced a window in the nave. You can tell which one by his signature logo of three sheaves of wheat.

Then there is the carved oak reredos by renowned Gothic revival architect Temple Moore as a memorial to Lydia Dawnay and the pipe organ by Isaac Abbott of Leeds.

During all this change there has been one constant, though – the bells. Two of them bear the words 'Jesus be our speed', with the dates 1619 and 1621 respectively cast on them. The third reads "Christus est lux, vita, et veritas'. (Christ is the light, life and truth).

Other highlights include the Grade II Listed Lych gate, which originally stood nearer and parallel to the church, while in the chancel an intriguing brass plate displays effigies of William Henry Dawnay, the sixth Viscount Downe and his wife who died in 1846 and 1848 respectively.

But All Saints isn't just a place of memorial to the occupants of Beningbrough Hall and Newton. During the Second World War the stately home was given over to personnel stationed at nearby RAF Linton-on-Ouse and being a bomber base, it wasn't long before the churchyard was called upon to provide crews with their final resting place.

However, the numbers proved overwhelming and an area at Harrogate's Stonefall Cemetery was set aside from 1943. At All Saints a neat little row of white headstones serves as a reminder of those dark days of the early 1940s.

The church did have a more cheery use for crews however, who knew they were home as soon as the huge spire came into view.

"I have been told that when lit it can be seen from the White Horse," says Neil. "Perhaps this year I shall go and see if that is actually true."

• All Saints, Newton on Ouse has recently been placed on the English Heritage at risk register, mainly due to the poor condition of the failing roofs. Volunteers are now working hard to raise funds for a full re-roofing and are set to make an announcement about their progress in the next few weeks.

This month's coffee morning falls on All Saints Day, which is also the annual gift occasion and the church will be open to visitors all day.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel