In a village near York, instrument-maker Richard Smith makes the finest brass instruments that have heralded occasions from the Olympics to royal weddings, reports MATT CLARK.

RICHARD Smith isn't simply a maker of brass instruments, he's the maker of brass instruments. You will have heard his fanfare trumpets opening the London 2012 Olympics, at the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge's wedding and during ceremonies to mark the Queen's Diamond Jubilee.

They also herald the beginning and end of the Grand National, while the world record for the longest fanfare team is held by 91 soldiers, all of them playing Richard's instruments.

And they are made in a village just outside York.

Richard founded his business as the theorist with partner Derek Watkins, whom he called the practitioner. It was a winning combination, with Richard using quantum physics to design instruments, having written a doctoral thesis on trumpet acoustics.

He went on to join Boosey and Hawkes, where for 12 years he was chief designer and technical manager responsible for the world-famous Besson brass range.

Richard also produced trumpets for Derek, who played with Johnny Dankworth, Benny Goodman, Frank Sinatra and the James Last Orchestra. Later he became Richard's design consultant until his death in 2013, and exclusively played Smith Watkins instruments.

"I made him up an instrument; bell and valves all lashed together with sticky tape and plasticine, so that he could change leadpipes until he found the arrangement he wanted," says Richard. "Then he said I need to change the leadpipes depending on the mood, or use an easier one for the last show of the day.

Since then people have waxed lyrical about Smith Watkins calibrated leadpipes, the pipe immediately after the mouthpiece, which enable changes in musical quality or adapts to the playing environment.

And with nine different pipes to choose from a player can get precisely the tone and response they are looking for. Generally the smaller the pipe the brighter the sound and the easier it is to play.

Which means there's one to suit everyone, from novice to virtuoso.

Best of all, it's easy to change from one note to another without getting hidden surprises and without having to correct the instrument all the time, a real boon for beginners.

"It was born from my understanding of trumpet acoustics and being able to work out what I can do to change the notes in pitch, strength and quality," says Richard.

Another of his brilliant inventions is a tone generator, as seen on Tomorrow's World, which shows that a trumpet can be played by machine. It replicates the vibration of lips and the pitch changes with temperature, pressure, moving a slide or pressing a valve.

Richard also hooks the box up to a rubber tube trumpet and the same thing happens just by pinching in various places. It's all to do with changing the diameter at a nodal point, he says, not to mention a perfect way to illustrate his findings.

So too is his airless trombone.

"A bee in my bonnet is that players are often taught to blow more air because it makes better notes. One of my demonstrations is to suck instead of blow and still play a note. It helps to show players why air is required, and that is simply to make the lips vibrate."

Richard proves his point by using a special mouth piece with a tube on the side that expels all the blown air away from the instrument. But still it plays.

"That really knocks them out," he says.

Indeed, his whole life has been about knocking people out with witty demonstrations that dispel commonly held musical urban myths through quantum physics.

Another favourite trick is to use blindfold testing. Working with a psychologist, Richard invited the country's ten best cornet players to test drive his instruments in different set ups. All chose the same one and it was put into production.

"This didn't just show us which instrument they preferred, it also showed us how good the trumpet players were at judging. But we don't tell 'em that."

He reached for the blackout mask once again to prove there is no difference in a trombone's sound quality whether the bell is heavy or thin.

Once again theory came first; in the guise of a hologram test.

"No one had ever bothered to see if bells vibrate, but they do. The application was to see if a player could tell any difference, between them because another urban myth was that thin bells were good."

Attaching weights to disguise whether the musicians were holding a thin or heavy trombone, the tests began and no one could distinguish one from the other.

This led Richard to conclude it would be the same for varnish, silver or gold plate, even copper instruments.

"There's no point testing it," he says.

"They can't tell the difference between thick and thin bells and this is just another layer. The bottom line is I don't bother about materials at all."

The biggest surprise at Richard's 'factory' is the scale of operations – or rather the lack of it. Indeed this is a two man show.

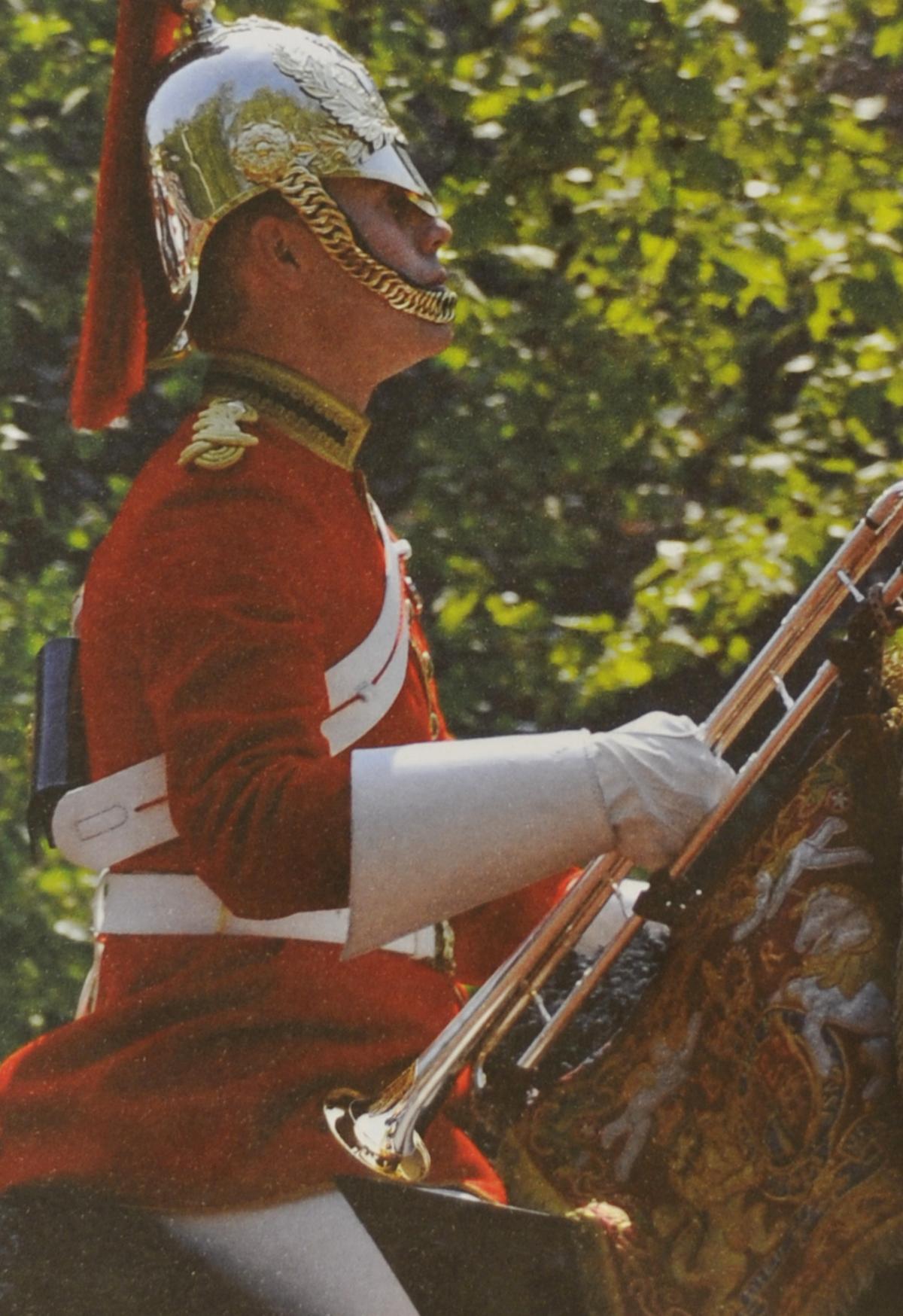

But small is beautiful and Smith Watkins is the Stradivari of the brass world, which is why they are the instruments of choice for most British military bands and professional soloists. But the company's fanfare trumpets are perhaps its crowning glory.

"They're bent for convenience," says Richard. "I came across a 13th century engraving of the seal of Portsmouth showing an admiral's barge with two straight trumpets that were used for signalling. There are no relics, this is the only evidence I've seen of a long trumpet being played."

There are four sizes in common use today. In a team of seven players, the British Army uses four B-flat melody trumpets, two B-flat tenor fanfares (similar to tenor trombones) and a bass fanfare pitched in B-flat.

The bands of the Royal Air Force and the Royal Marines add a soprano fanfare.

"The sight and sound of these instruments is quite spectacular, whether on the parade ground or at a Royal celebration," says Richard. " Two trumpeters played my trumpets at the state opening of Parliament in jubilee year, 2012. For me that really was a great thrill."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here