This week the month-long Yorkshire Medieval Festival turns its attention to early combat methods. As MATT CLARK discovers, they are surprisingly familiar.

MARTIAL arts conjures visions of little Johnny winning his brown belt or Bruce Lee in those Seventies movies. So it may come as a surprise to learn that codified systems of combat were prevalent in England hundreds of years before the dragon entered these shores.

Indeed they helped to keep our longbowmen in such prime condition that they were feared across medieval Europe. Not only as archers, the men also trained with the sword and buckler, which made them outstanding shock troops once the supply of arrows had run out.

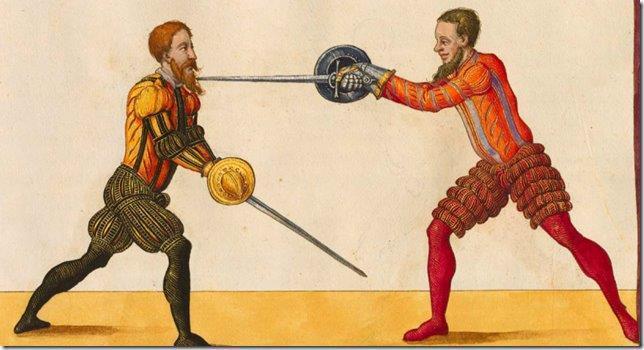

The term martial arts may derive from Mars, the Roman god of war, but combat activities such as single cudgel, double cudgel and long lance weren't the exclusive preserve of professional soldiers. Late Medieval German fechtschules became like gentlemen's clubs, where it was more about the art; about beating your opponent or putting on a show for spectators.

And there was a set of rules to ensure nobody was hurt.

Christopher Halpin-Durband is on a mission to bring back these ancient activities. Not as historic re-enactments, or theatrical stage-fighting, but as a modern sports discipline. It’s a lost heritage, he says. One that still has a great deal to teach us.

Christopher is master of York's chapter of the Hotspur School of Defence, which is dedicated to promoting and teaching these art forms. This week, as part of the Yorkshire Medieval Festival, he and his team will be running workshops at the Guildhall, to show how the principles behind medieval martial arts relate to modern fitness and self-defence training.

"Western warriors were taught from childhood to use the same set of body mechanics to elite athletes or marines: namely, strength and stamina, timing, balance, and speed," says Christopher. "Training techniques, the manufacture of arms and armour, and expertise in the martial arts all reached such a pinnacle in the Middle Ages, that they cannot be surpassed today. "

Knights were not just part of a savage mob waving swords around: they were tactical, cunning and exceptionally skilled. In fact, squires could spend years learning techniques such as running or lifting weights, before being allowed to wield a sword.

We can still read about the tactics they used in a surprising number of Middle Ages combat manuals. It's fascinating stuff and don't be fooled into thinking sports science is a modern invention, either. Many of its principles are preserved in manuscripts from the 13th century, but they go back even further.

"It's an age-old thing. These people trained day in, day out, from childhood and that included diet," says Christopher. "Indeed, we know that Roman gladiators ate a lot of barley and vegetables, to pack on muscle and gain a layer of fat that would absorb blows. They were strong but deliberately bulky."

In the Middle Ages bespoke techniques were even designed to help ordinary folk beat stronger opponents or ones in better physical condition; literally punching above their weight .

Martial arts schools, or scholes of fence were known to have existed in England at least as early as the 12th Century. Many types of weapon skills were taught, often alongside one another; some we don't know much about, such as seax, forest bill and black bill. Others are more familiar including the chivalric tradition of training in plate armour both on foot and on horseback.

Now these traditional disciplines are making a comeback.

"This is the fastest growing sport across Europe," says Hotspur instructor Neil Tattersall. "And we've got all these wonderful sources with superb illustrations. But they are just snapshots of the play as it progresses. We have to look at the most efficient way of making them work."

Many of the texts are written in High German and Latin. Now scholars are translating them and trying to make sense of the missing bits. But there are more than enough clues to piece together how these ancient moves would have looked to contemporaries.

"As you look through the pictures a lot of [wrestling] locks and holds are just the same as you'd find in jujitsu," says Neil. "They are quite possibly 1,000 years old. Body mechanics don't change, we have two arms and two legs and we can only move in a set number of ways."

The manuscripts also describe in detail how to perform unarmed grappling, quarterstaff and pole arms, not to mention wrestling, at which we apparently once excelled and is now a favourite with Abi Smith, Hotspur's newest recruit.

"It's very unusual, that's what's so appealing and it's just so much fun," she says. "I didn't know about medieval martial arts before I joined and it came as a shock to realise it was so big a thing."

The pinnacle of medieval martial arts was longsword fencing and Johannes Lichtenauer's medieval treatise Fechtbuch still forms the basis of Germany's school of swordsmanship.

"Fencing is always about being nimble," says Christopher. "This Hollywood idea of two grizzly heroes striking into the binder of the sword and grimacing at each other never happens in the manuscripts. You never fight strength with strength, every manual tells us to be quick and agile."

They even have a word for fighters who prefer brute force to skilled endeavour: Buffaloes.

The swords used by the school are the real thing and in wrong hands could cause serious damage. Indeed Christopher will be giving a lecture tonight entitled Lacerations and Perforations: The Physical Effects of Sharp Force Trauma, which draws parallels between medieval and modern combat.

But his wife Emma says don't get the idea that medieval martial arts are dangerous. Training at the school follows methodologies laid down in historical texts, with an emphasis on achieving a solid grounding in the basic footwork and body mechanics before techniques are introduced.

Wooden knives and swords are then used by beginners, not only for safety, but because they are lighter and easier to use. Only when a new student has proven their worth with these practise weapons are they are allowed to use ones forged from steel.

"It's all very safe, though" says Emma. "Occasionally you get a bang to the hand but that's it."

The same goes with wrestling, boxing, long knife work and all the other weird and wonderful skills being revived from a millennium ago. The emphasis here is on winning with grace, not through strength.

"Western martial arts have huge relevance to today," says Christopher. "This is a unique discipline and a living heritage that should be championed. Why shouldn’t these skills be taught in our leisure centres?"

Fact file

Daily medieval combat classes with Hotspur School of Defence will take place Monday to Friday this week between 11am and 5pm at York Guildhall. Prices £7 adult, £5 concessions, £20 family of 4, £25 family of 5.

Emma Halpin-Durband will deliver her lecture Lacerations and Perforations: The Physical Effects of Sharp Force Trauma tonight at 6.30pm in the Mansion House.

Another lecture Hollywood & The Sword: Dispelling Popular Myths about Medieval Combat will take place on August 22, again 6.30pm in the Mansion House.

Tickets are £4 Adult, £3 Concessions for each event,

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here