It might look unassuming from the road but St Mary’s Church in Bishophill hides a wealth of secrets. MATT CLARK asks Churchwarden Graeme Thomas and York Diocese tourism officer Roy Thompson to reveal a few.

HOW many people know that Fetter Lane is named after manacles for restraining prisoners? Probably very few was the passing thought while walking up the road off Skeldergate to Bishophill.

Another passing thought was how many people in this part of York know that their church pre-dates the present Minster? Probably even fewer, but nestling amid a sea of Victorian terraces and modern flats is St Mary's Church and its tower was built before the Norman Conquest. Which makes it the oldest piece of ecclesiastical architecture within the city walls.

However, there's something curious about that tower. Half way up you spot a change in construction. The herring-bone pattern in the lower section is clearly Saxon, but differences further up suggest the belfry is quite a bit later.

No matter. The base is from about 960AD and that's what counts for the record books.

The conundrum continues with some Roman bricks and tiles in the meld. Now what's going on, you wonder. The answer lies in 10th century recycling, because St Mary's is sited in what was once the colonia or civil quarter of the Roman garrison of Eboracum. When the tower was built, hundreds of years later, stone from the ruins was re-used, which makes this church unique, certainly in York.

As does a huge internal archway between the tower and nave. It's far sturdier than the Gothic and Norman examples elsewhere in the church and churchwarden Graeme Thomas reckons it has to be Roman.

"I can't see how the Saxons would have had the skill to make it," he says. "I would've thought they'd have robbed a whole arch and I think what we are looking at is essentially Roman. What else could be that shape?"

Roy Thompson, of York Diocese agrees.

"With all that stone from the colonia around, the Del Boy of the day would have been able to say: 'You want an arch? I've got an arch, it'll just fit nicely'," he says.

The tower may be St Mary's jewel in the crown, but even without this church would still offer a fascinating history lesson.

Much of it was built from the twelfth century through to the medieval period. Again by 'borrowing' stone, this time from the defunct city walls, which, by then, had effectively become a quarry.

Enlargements were made in the 11th and 12th centuries with additions during the 13th and 14th. Which means the nave has classic examples of Norman arches along one side, Gothic arches along the other, not to mention a rare 15th century beamed roof.

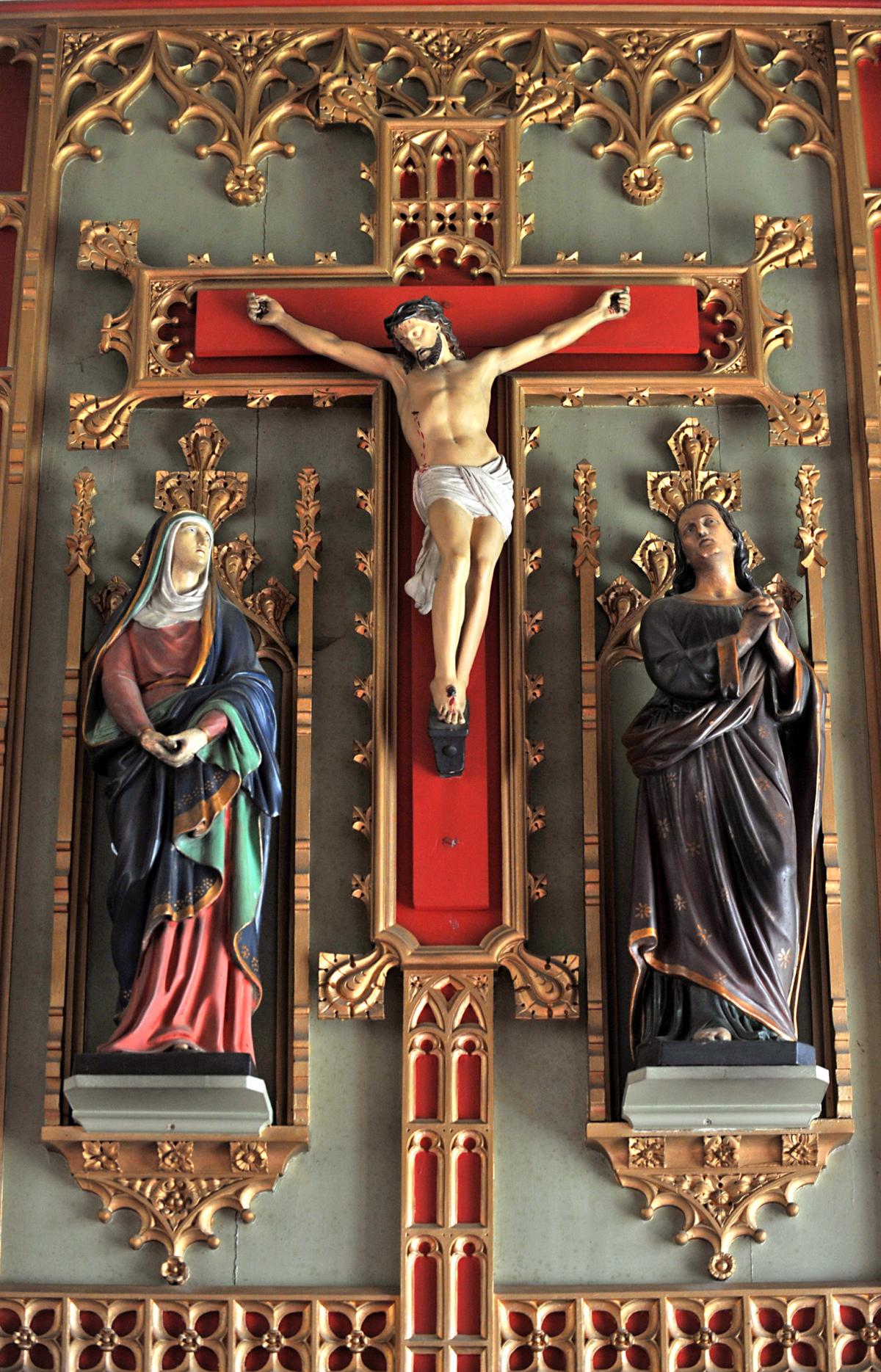

Then it all changes dramatically as you enter the chancel which was re-ordered in High Victorian style with a remarkable Gothic Revival reredos by Temple Moore. It dates from 1889, four decades after the Oxford Movement had developed High Church into Anglo-Catholicism and reinstated some 'lost' Christian traditions of faith.

The whole crux was to move focus away from the preaching box, back to the high altar and Moore's reredos is designed to add a sense of theatre.

"A lot of this period is about turning the chancel into a stage," says Roy. "It becomes a performance area, from something that had previously been cut off completely and where the people were preached at.

"Suddenly they are invited in to take Communion week by week rather than four times a year."

Temple Moore was also responsible for St Mary's pulpit and choir stalls. Whereas the Oxford Movement revived early church rituals, his use of design features such as double ogees on the pulpit harks back to pre-reformation architecture.

It stems from Augustus Pugin's call for an end to plain Regency panelling and a return to 'proper' architecture and decoration. Something that would impress.

Height in churches was also important to Victorians, nearer my God to thee, that sort of thing, so contrast St Mary's tall vaulted chancel ceiling with the flat low Elizabethan one in the nave. But not all is as it seems.

"In a sense St Mary's wasn't High Church," says Graeme. "It was the priests who took it in that direction, even up to the 1980s and the Minster kept a watchful eye. They wouldn't have wanted it to go too Roman."

The font is another surprise with its fine Jacobean oak cover. Cox and Harvey in their 1907 book, English Church Furniture, suggest that, "Fonts were ordered to have covers and to be kept locked for the double purpose of cleanliness and for checking the use of the water for superstitious purposes."

Roy says the Puritans also chose to cover their fonts out of modesty.

They have been in use from early times, and were originally flat with notches in the lid and basin to hold the cover in place, St Mary's on the other hand is gloriously flamboyant with an open coronal, crisply carved finials, urns and flowers.

Further surprises await on the church noticeboard, which tells you St. Mary's is in the Archdiocese of Thyateira and plays host to the Greek Orthodox congregation of St. Constantine and St Helen as well as York's Russian Orthodox community.

All this from an unassuming little church nestled among a sea of Victorian terraces and modern flats.

"This is living history; a lovely old place and with a nice scale," says Graeme. "And it fascinates me that the two most prominent objects here (the Saxon tower and Temple Moore's reredos) are separated by almost 1,000 years."

Make that almost 2,000 years if you count the Roman arch.

Anglican services at St. Mary's Bishophill take place every Sunday at 0915. The Russian Orthodox Church meets the first Saturday of the month at 10am, while The Greek Orthodox Church attends on the second and fourth Sundays at 11am.

St Mary's is also participating in The Yorkshire Medieval Churches Festival and will be open to the public on Thursday August 7 between 2-6pm.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here