Once, many of our historical treasures languished unseen in dusty vaults. Now, with the help of the internet, York’s museums are letting the world discover more about the city’s jewels. MATT CLARK discovers how it’s being done.

WHAT on earth did we do before the internet? These days every conceivable fact, and quite a few wrong ones, can be had at the touch of a fingertip. But have you ever wondered how all this stuff gets online? Who are these anonymous folk making our lives so much easier?

Well, one of them is Pat Hadley, working as York Museums Trust 's Wikimedian in Residence.

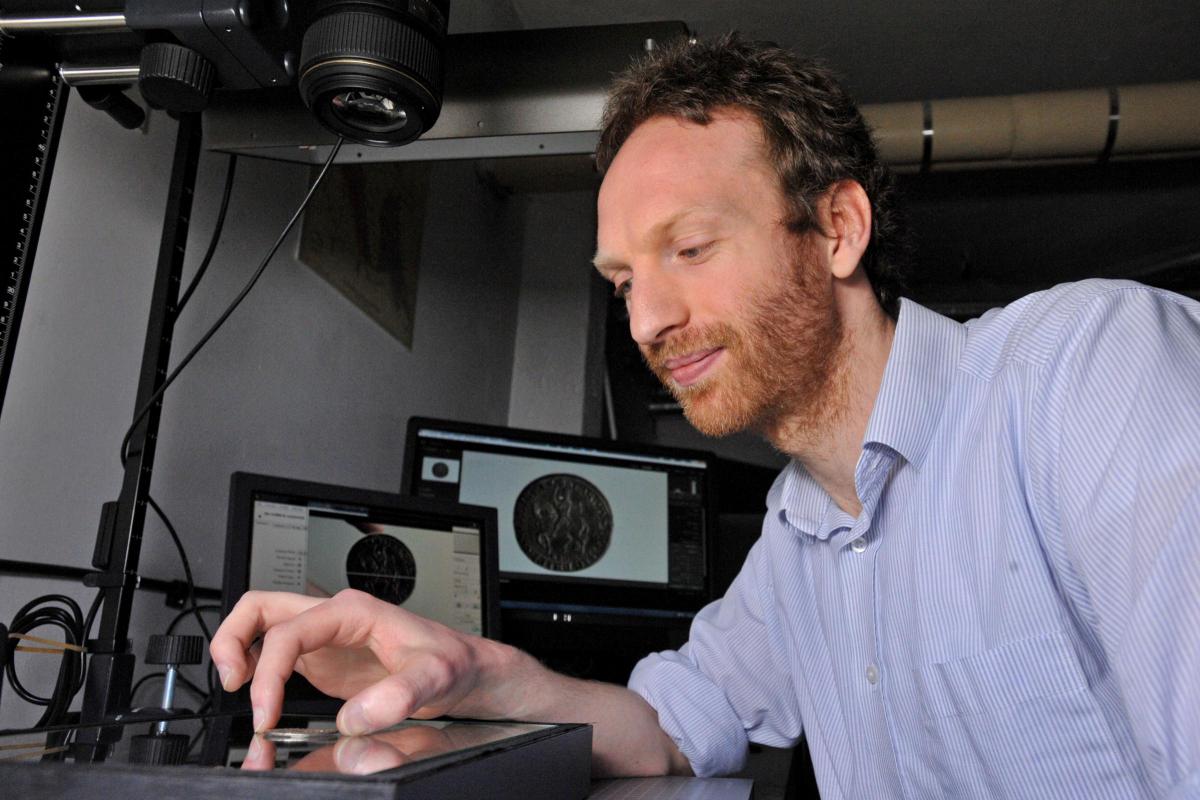

This is a first for the region. Elsewhere museums are at various stages in the digitisation process, but York is leading the way thanks to its new photographic suite.

"We are definitely pioneering," says digital team leader, Martin Fell. "For the first time we have really good images, our websites are being redeveloped and we will be offering access to some 150,000 records with images bundled alongside."

But not for a while. Each coin takes a minute to photograph both sides and if the curators tried to do the whole collection in one sitting, Martin says it would last about a year and a half.

"It can be difficult to come to grips with this process, but it has to be welcomed, " says Martin. "Openly licensing our content means other people can use it in interesting ways as well, which is going to be hugely beneficial."

However, reaching a global audience isn't going to happen by relying solely on the York Museums Trust website. And that is why Martin applied for Pat's services.

"As I began to think about digitising our content formally, it made sense to put in a bid for a Wikimedian in Residence who would help us find a use for it," he says.

"The foundation is supported by donations and their funds are limited so, yes, this was a coup for us."

Pat works with the trust's digital team, curators and volunteers to upload pictures of museum collections for people to download and use them free of charge.

It is part of the global project known as GLAMWiki (galleries, libraries, archives and museums) which was set up to help institutions get their content and knowledge online.

But Wiki etiquette means Pat cannot write about the photos. That is a job for the website's volunteer editors.

"I donate the images to Wikimedia Commons and do my best to engage with them and say look there's this resource, let's get it out there in articles," says Pat.

But that can be easier said than done, because Wikipedia requires proof from an external source. It doesn't work to the truth, Pat says, it works to verifiability.

That said, blog posts citing empirical evidence can be enough for editors to establish truisms. But where more than one opinion exists, each is given equal weighting.

Even more tricky can be attracting volunteers to write something about an uploaded image.

"It can be difficult to ensure the project is picked up," says Pat. "But the offer is there now in a way it never was before."

And not just to use the content online, but in things like text books or brochures, anywhere on the planet.

"Wikipedians try to liberate content from organisations who aren't giving it away for free but should be," says Pat. "I'm here to act as an intermediary between resources, knowledge and expertise, the platform for sharing and the volunteer editors."

Another role he was asked to take on is promoting the colourful life of York volcanologist and adventurer Tempest Anderson to a global audience via Wikipedia platforms.

Which is a good thing, because Anderson is hardly known outside Yorkshire and even within the county, precious few will have seen his astonishing photos.

Soon they can, because the trust's partnership with Wikimedia UK will see far more information and images being uploaded to illustrate his life and interests among new audiences.

"Anderson took fantastic photographs of eruptions and daily life while on his travels around the world," says Pat. "The idea of this part of the project is to see digital scans of the glass plates being put on Wiki Commons for people to use and enjoy."

An archaeologist for the last decade and for two years a regular contributor to Wikipedia, Pat brings to his new role the ideal mix of a passion for history and a wealth of experience in sharing knowledge through digital media.

He also believes museums should remain custodians of the physical objects, but the knowledge and stories they hold should be shared more broadly.

"Museums are going from guardians of their collections to being guarders," he says. "By giving away their content they are allowing new creativity to happen for the rest of the cultural sector or education sector or anyone else to pick up on stuff that used to be stored away ."

Pat's images have already yielded articles, including one about the Yorkshire Museum's Middleham Horde and images of it are currently used by a number of continental websites.

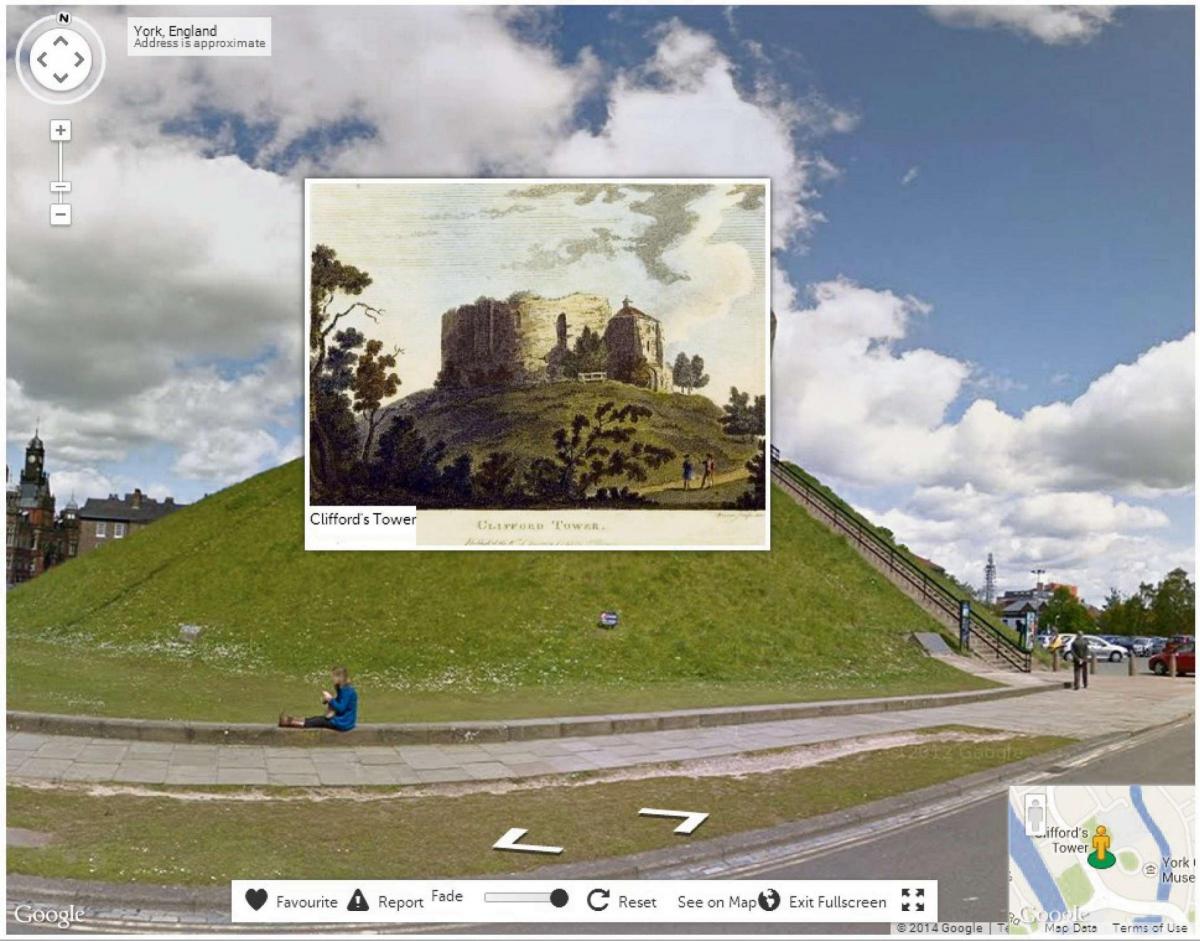

Then there is Historypin; a way of superimposing old photographs onto their contemporary setting using Google maps.

To Pat history on the internet is the way forward. For museums to think about their audiences in new ways and engage with people on a global scale.

"Wikipedia projects are like fertiliser," he says. "But the important thing is it has to be used in a way that changes things."

Would you like to write an article for Wikimedia based on images posted by Pat? If so visit: www.yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk for contact details.

Tempest Anderson was born in York in 1846 and became an ophthalmic surgeon at York County Hospital.

He was an expert amateur photographer and volcanologist and a member of the Royal Society Commission which was appointed to investigate the aftermath of the eruptions of Soufriere volcano, St Vincent and Mont Pelee, Martinique, West Indies, which both erupted in May, 1902.

Some of his photographs of these eruptions were subsequently published in his book, Volcanic Studies In Many Lands.

Anderson went on to serve as President of the Yorkshire Philosophical Society, and in 1912 he presented the society with a 300-seat lecture theatre (the Tempest Anderson Hall) attached to the Yorkshire Museum in Museum Gardens. It was one of the world’s first concrete buildings.

Anderson died on board ship in the Red Sea while returning from visiting the volcanoes of Indonesia and the Philippines. He was buried in Suez, Egypt, and bequeathed a substantial sum to the Yorkshire Museum.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here