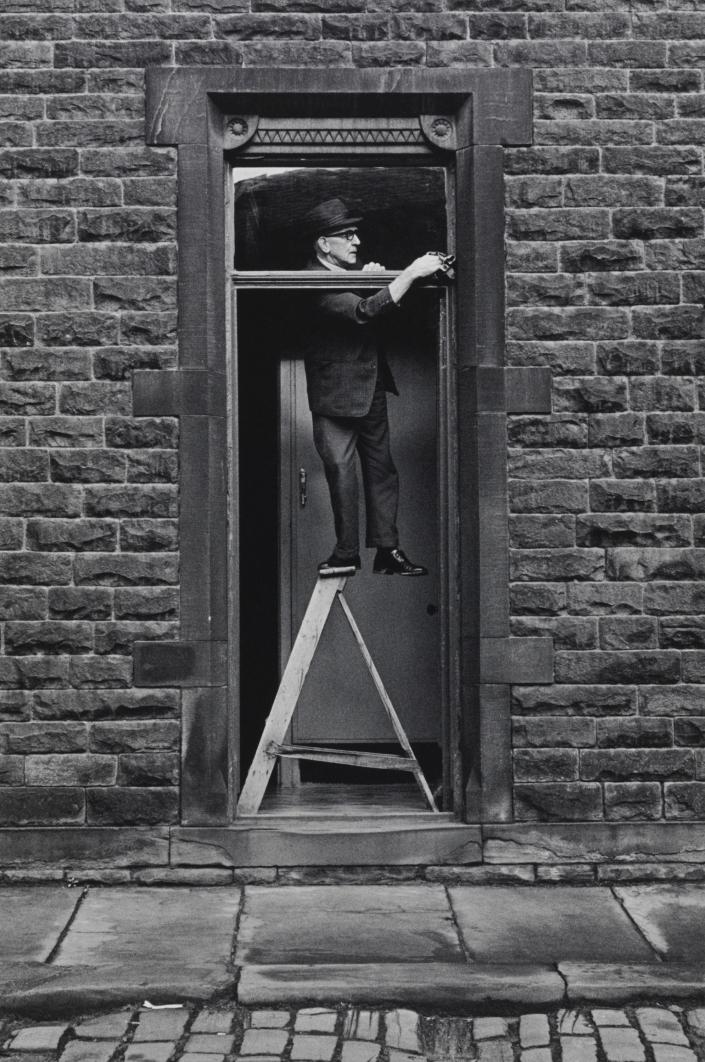

"DO NOT take boring pictures," Tony Ray-Jones wrote to himself as he set out to photograph his now iconic images of the English.

Over three years in the late 1960s, he travelled the length and breadth of the country in a VW camper van, photographing fairs and celebrations, the seaside, village fetes and processions.

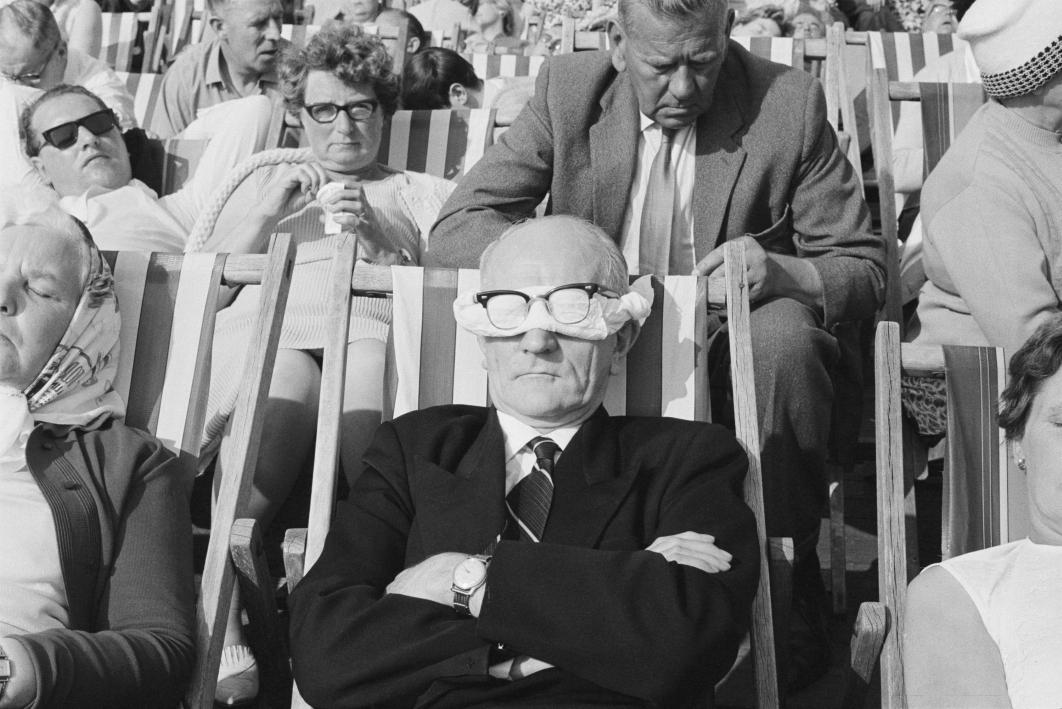

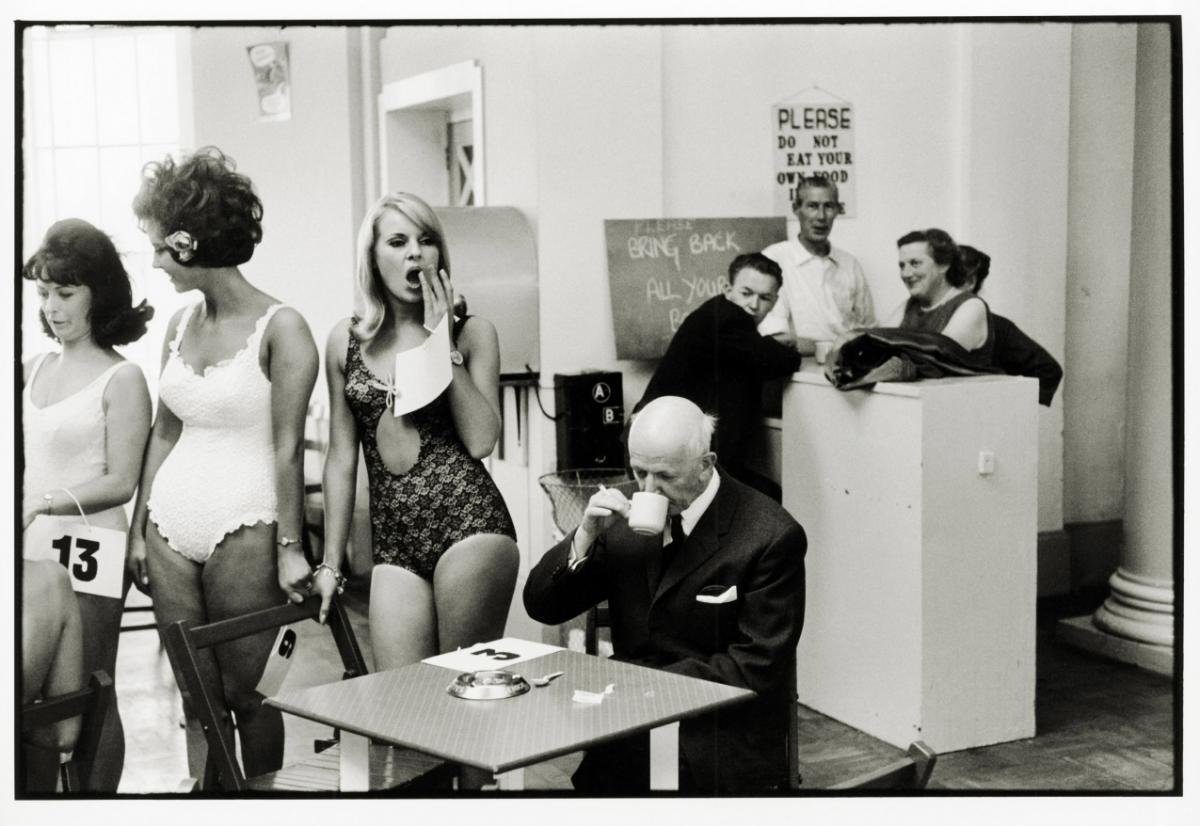

He had a clear vision of what he wanted his pictures to show. He knew this was where people were at their most relaxed, and where they would be absorbed by their traditions, and in these everyday situations he could photograph the 'gentle madness' of the English.

For many years the style he created was considered among the most influential in British photography, but it wasn't until last year when his pictures were chosen for the inaugural exhibition Only in England at the Science Museum's new Media Space that they were given wider national recognition.

The exhibition includes more than 50 prints never before seen which were selected by photographer Martin Parr from negatives stored in the collection at the National Media Museum in Bradford, where the exhibition was created, and where it is on now until the end of June.

Tony Ray Jones spent time in America and learned from photographers such as Robert Frank and Garry Winogrand, but he stayed true to his own artistic vision.

"The situations are sometimes ambiguous and unreal, and the juxtaposition of elements seemingly unrelated, and yet the people are real. This I hope helps create a feeling of fantasy.

"Photography can be a mirror and reflect life as it is, but I also think that it is possible to walk like Alice, through a looking-glass, and find another kind of world with the camera," Tony Ray Jones said.

At Glyndebourne he photographed a couple lost in their tradition of the perfect picnic, the distance between them is like the distances between animals wandering around the field behind them; at Wimbledon he found an odd couple in sunglasses; at Broadstairs he photographed the Dickens Festival, and in Bacup, the Coconut Dancers.

His pictures are "of situations which are immediately funny but also are imbued with a hint of melancholy. They become almost like films contained in each single image in the sense they have narrative threads running through them," says the curator of the exhibition, Greg Hobson.

Tony Ray Jones died when he was only 30, but he left behind a legacy that changed the face of British photography, influencing many young artists including Martin Parr, whose early black-and-white work, The Non-Conformists, is part of this exhibition.

“Tony Ray-Jones’ pictures were about England. They had that contrast, that seedy eccentricity, but they showed it in a very subtle way. They have an ambiguity, a visual anarchy. They showed me what was possible,” said Parr.

His photographs in this exhibition document a declining traditional way of life in Hebden Bridge in the 1970s.

They look inwards into a relatively small tightly knit community based around small mill related industries which were failing, hill top communities, social centres and non-conformist chapels.

Parr was documenting a way of life that was being encroached on by the modern world – "cobbled streets, flat-capped mill workers, hardy gamekeepers, henpecked husbands and jovial shop owners".

In the five years he spent taking photographs from 1972, Hebden Bridge was changing in front of his eyes.

His photographs capture the end of an era, the lives of the last generation of people whose fiercely independent lives were defined by their non-conformist roots.

Parr and his wife, Susie, became involved in the community, they were there at the very beginning of the gentrification of Hebden Bridge.

Like Ray-Jones, Parr's photo's are full of affectionate humour and focus our attention on the aspects of traditional life that were beginning to decline, but they also stretch to a wider meaning – in 'Jubilee Street Party, 1977', a table laid with a traditional Yorkshire feast is left full of food but empty of people because flood waters are coming in.

It has been 35 five years since Parr finished this project, since when photography and his own career have developed through globalisation and the digital revolution to the point where we are swamped with published images every day, whose power Parr has termed 'propaganda', and whose power his own photographs contest.

This exhibition finally sees the publication of these photographs in a book The Non-Conformists, one of more than 80 photo books to his name. Many of these question photo 'propaganda' in a humorous way, reflecting the changing nature of documentary photography, many are still about documenting the English, which he is still doing today - for the past four years he has been photographing the Black Country.

"Documentary photography's role is to challenge our daily dose of photo propaganda" he says.

Only in England is at the National Media Museum, Bradford until the end of June.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here