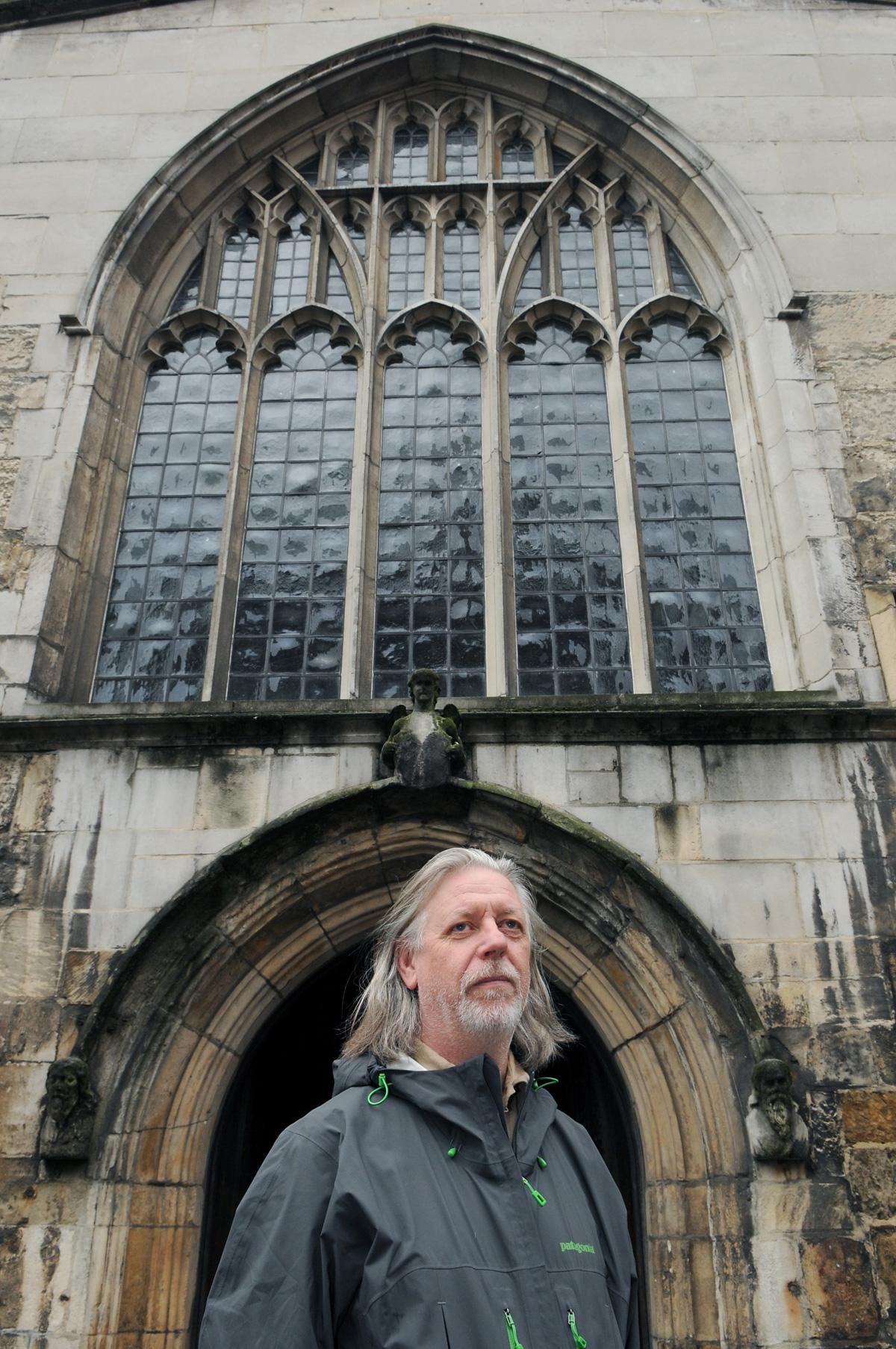

City archaeologist John Oxley has a wealth of knowledge about York’s past. He makes the perfect guide for a walking tour following in the footsteps of Richard III. STEPHEN LEWIS reports.

AUGUST 29, 1483 was a big day for the people of York. Their King was coming home. Richard III had been crowned at Westminster Abbey on July 6. A few weeks later, he set off to tour the country, with his court and the machinery of government in tow.

But York, the capital of the North and his favourite city, was always his destination. And on the morning of August 29, he arrived.

He had given the city fathers plenty of notice. Six days earlier, the King’s secretary, John Kendall, had written to warn of Richard’s arrival.

“I truly know the king’s mind and entire affection that His Grace bears towards you and your worshipful city, for your many kind and loving deservings shown to His Grace heretofore,” Mr Kendall wrote. “His Grace will never forget, and intends therefore so to do unto you that all the Kings that ever reigned over you did never so much, doubt not hereof…”

There were some words of advice, too, however. Throughout their journey north, the King, his Queen Anne Neville, and the members of their court and retinue, had been “worshipfully received with pageants”.

“I advise you to receive him… [with] … such good speeches as can well be devised… for there come many southern lords and men of worship with them which will mark greatly your receiving [of] Their Graces…” Mr Kendall wrote.

In other words, says city archaeologist John Oxley, York was being advised to prepare a grand reception for the King.

“It was a case of ‘get your act together. You’ve got to put on a good show. But you’ve done well by Richard in the past, and he’s going to do well by you in the future’.”

And so he did. The new King spent three weeks in York. During that time, he halved the taxes the city corporation had to pay, Mr Oxley says – and had his son Edward of Middleham invested as Prince of Wales at York Minster. York, it was clear, was going to do well under this new monarch.

Ever since Richard’s remains were found beneath a Leicester car park last year, a row has raged between York and Leicester over where he should be buried. A judicial review is due shortly.

Given the huge interest in Richard, now is a good time to launch a series of guided ‘walking with Richard’ tours of York. And that is exactly what Mr Oxley has done.

There are three this autumn, and a further three next spring.

The first of the autumn tours was held last week; the second starts from the Mansion House at 2pm today; and the third will be next Wednesday, starting from outside the west door of York Minster.

The amazing thing about York, says Mr Oxley, is that the basic layout of the streets hasn’t altered that much from Richard’s time.

“Many things have changed, but the townscape today is one that Richard would still have recognised,” he says. “And we really can actually walk in Richard’s footsteps.”

Mr Oxley, with his wealth of knowledge about York’s past, makes a hugely entertaining and informative guide.

Meantime here, with Mr Oxley’s help, is our own guide to some of the places in York with strong Richard III associations.

• John Oxley’s next ‘walking with Richard III’ guided walk is this afternoon (Wednesday October 9), leaving from the Mansion House at 2pm.

There will be another walk next Wednesday (October 16), meeting at the west door of York Minster at 2pm, and a further three walks next spring (March 12, 19 and 26).

There is no charge, but places are limited to 25 people per walk. To find out more, or book a place, visit archaeology@york.gov.uk or phone 01904 551346/ 551671.

Guildhall

The Guildhall – or Common Hall as it was known – had been built in 1445 for the use of the York Corporation and the Guild of St Christopher and St George. Richard may well have been entertained to at least one banquet here during his three-week stay in the city in 1483.

The King and his most prominent guests would have taken their places on a dais at the end of the great hall nearest the river.

Less important guests would have been seated on trestle tables stretching the length of the hall.

The first thing to have been brought in, says Mr Oxley, would have been pitchers of rose-scented water for the guests to wash their hands. Then ‘plates’ would have arrived: slabs of heavy, coarse bread.

The guests would not have eaten this, Mr Oxley says: it would simply have been used as a platter, or trencher. “It would have been taken out afterwards and given to the poor.”

So what would have been on the menu? We have a pretty good idea, from a contemporary menu.

The guests would have drunk wine and beer. There would have been bread and softened butter to start, followed by an ‘entrement’ to prepare the stomach, possibly leek poached in white wine.

Other dishes might have included green soup of almonds, roasted beef with pepper sauce, sliced breast of chicken in cinnamon sauce, a ‘great pie’ of venison, pork and veal, baked trout in ‘sauce galantyne’, boiled turnips with chestnuts, and sliced apples fried in ale batter. And that was just the first course.

Micklegate Bar

In Richard’s time, as now, Micklegate Bar was the official point of entry into York for reigning monarchs.

The Kingship back in 1483 was itinerant, Mr Oxley says – it moved around with the King, and when he travelled, he brought the machinery of government with him.

So you can picture Richard’s arrival in York that August of 1483: a long train of horses and carts trundling along the muddy cobbles of The Mount and Blossom Street, with the King smiling and waving from horseback at its head to acknowledge the cheers of the crowds lining the street.

It would have been a long procession. “He would have brought all the paraphernalia of the King and court with him including the Treasury,” Mr Oxley says. So there would have been chests of gold, carts full of documents and court records, and hundreds of officials, secretaries and retainers; everything the King needed to administer his country.

As this procession approached the barbican which then stood in front of Micklegate Bar, the whole city would have come out to watch, leaning from the houses which lined the narrow cobbled street.

At the bar, Richard would have been greeted by the Mayor and the city’s leading figures, and there would probably have been a great pageant, Mr Oxley says.

There is no surviving record of such a pageant: but there is a written account of the celebrations that marked the entry of Richard’s successor, Henry VII, into York less than three years later.

A ‘representation of Heaven’ was fashioned above the bar, from which a crown dropped down into a representation of earth, full of trees and flowers, below. Ebrauc, the legendary founder of York, then appeared and greeted King Henry, before presenting him with the keys of the city.

“Whether they did a similar thing when Richard came, we don’t actually know,” says Mr Oxley.

“But it is very likely they would have put on a pageant for him.”

Augustinian Friary, Lendal

Richard, whose power base had long been in the north, at Middleham and Sheriff Hutton, was a frequent visitor to York before he became King. One of the places he liked to stay was in the Augustinian Friary on Lendal. Founded in 1272, by Richard’s day it stretched most of the way along Lendal from roughly where the Post Office is today to Museum Street.

The actual Friary buildings may well have been hidden from the street behind a row of houses. But there would have been one or two entrances through to the Friary itself, which occupied the land between Lendal and the river. The alleys that today lead off Lendal in the direction of the river may well be the remains of these.

They look pretty uninspiring now. “But this may have been where Richard walked,” says Mr Oxley.

Processional route to York Minster and the Archbishop’s Palace

Having passed on foot through Micklegate Bar, Richard and his court would have passed along Micklegate, over Ouse Bridge, up Coney Street, and then along Stonegate to the Minster.

There would probably have been a number of pageants and ceremonies en route, says Mr Oxley. There may well have been one at Holy Trinity Priory in Micklegate; and another at Ouse Bridge. “The bridge then would have been like the Ponte Vecchio in Florence, with houses on it. The council also had their chamber there.”

The procession would have passed up Coney Street – with quite possibly another stop at the Guildhall – before passing along Stonegate towards the Minster, where there would have been a service.

The Minster itself, in 1483, sat within its own walled precinct. The main entrance to this was at Minster Gates. Stand half way along Minster Gates today and look towards the Minster, says Mr Oxley, and you’ll be in almost the very spot where Richard was greeted by his archbishop.

During his visit to York, the King would have stayed at the Archbishop’s Palace, which in those days was in Dean’s Park behind the Minster. The ruins at the back of Dean’s Park which now serve as a war memorial are the remains of the palace’s cloisters. What is now the Minster Library, meanwhile, was once the Archbishop’s private chapel – where Richard probably prayed during his stay in the city.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here