Hurrying shoppers and scurrying tourists often miss one of York’s most important churches because it is hidden from view. MATT CLARK discovers why that’s a shame.

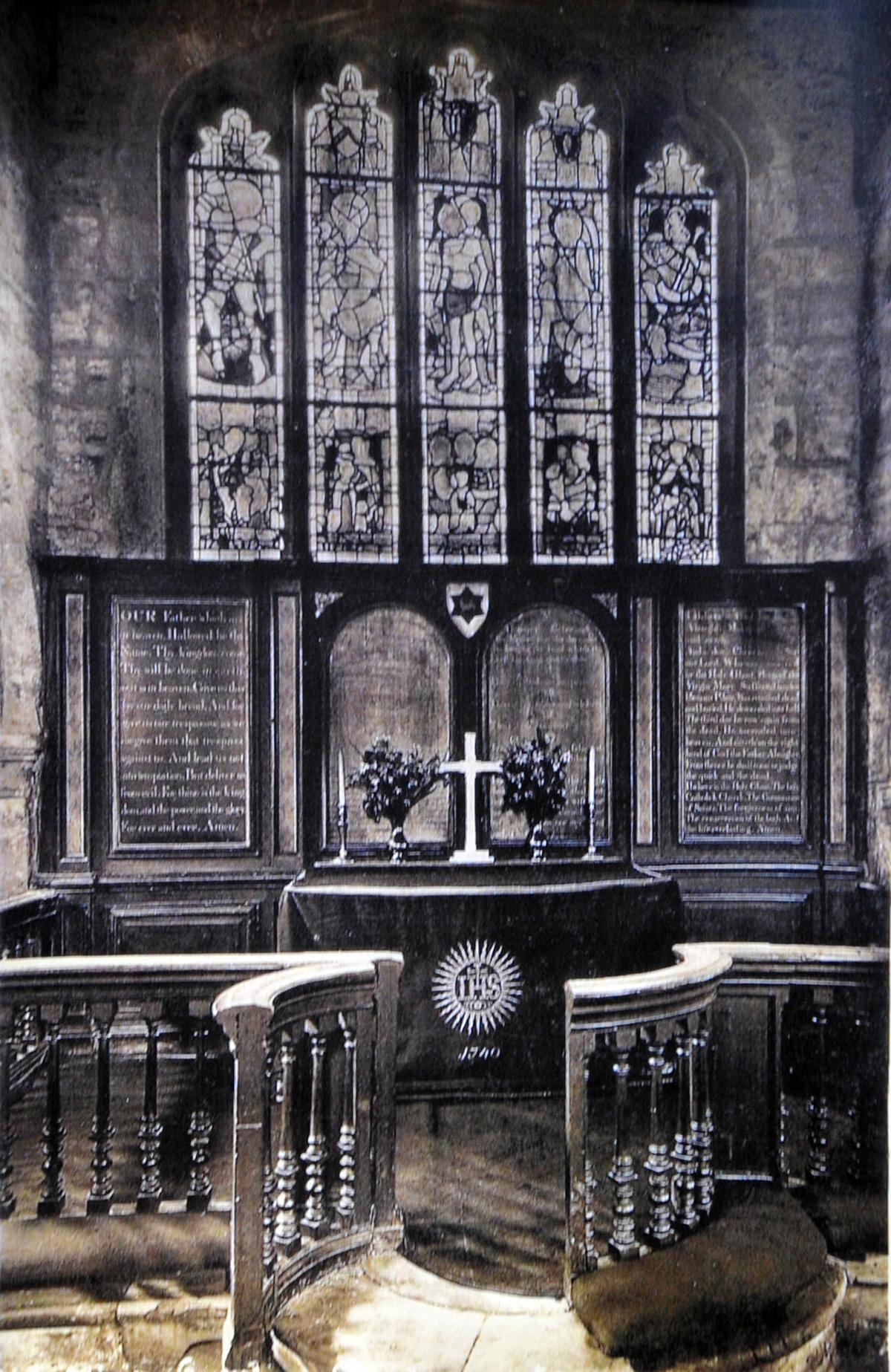

LIKE glowing rubies, dots of glass-stained crimson play across the honeyed walls at Holy Trinity Church in York. This is especially so from the 15th-century east window, which is one of England’s glories.

If you look carefully you can spot its benefactor, John Walker, the then rector, immortalised as a kneeling figure below the figures of the Trinity.

This is one of many rich rarities in a church you could easily miss, and many do, because despite being one of York’s most important buildings, it lies tucked away behind Our Lady’s Row in Goodramgate.

Holy Trinity is an oasis of calm, far from the madding bustle of a busy shopping street. It nestles in a verdant churchyard approached through a red-brick entrance, with gates made in the same year as the Battle of Waterloo.

While a church on the site was mentioned in charters of 1082 and 1092, as part of the foundation grant of Durham Cathedral Priory, the present building dates chiefly from the 15th century and has a singular double-sloping or saddleback roof.

But it’s the interior that makes Holy Trinity such a gem.

The church is an unspoiled example of an early Georgian parish church, thanks to the only surviving box pews in York. This probably explains why the BBC chose to film here for its forthcoming period drama, Death Comes to Pemberley.

Dawn Lancaster, of the Churches Conservation Trust, says box pews were a post-Reformation addition, at a time when all the focus was on the word of the Bible and on listening to the parson.

To that end the pulpit was situated near the middle of the nave so everyone gathered in their boxes could receive the benefit of lengthy and edifying sermons.

“This was your space and the whole family sat facing each together, listening and contemplating,” says Dawn. “The word was enough.”

Many box pews were comfortably fitted out, with embroidered cushions and rugs to keep off the chill. And the most prestigious and expensive ones were nearest the pulpit. By the 19th century, however, having a box pew as a status symbol began to be seen as iniquitous.

Indeed, the Bishop of Hereford argued that they served to “drive the poor to distant and damp situations far from the minister and the place of his ministration”.

Archdeacon Hare went further, calling them “wooden walls within which selfishness encases”.

But it was the advent of the Oxford Movement, an almost Catholic revival, that finally saw box pews fall out of favour, and for less contentious reasons.

Throughout the country, ceremony and pomp was returning to services, with pulpits back to their pre-Reformation position, which meant inward-facing box pews distracted rather than focused the congregation’s attention. So a widespread removal programme took place.

“They survived here because in the 19th century this area became quite poor,” says Dawn. “There just wasn’t the wherewithal, financially, to strip all of this out.”

Today box pews are a rare sight and that makes Holy Trinity rather special, because it perfectly illustrates post-Reformation developments in social history.

“It absolutely does and that’s one of the key things,” says Dawn. “The higher pews, which are more enclosed, reflect a social change where the traditional elite are adapting their behaviour to differentiate themselves from the rising merchant class. It was saying, we’re so exclusive, you can’t see us.”

But the best families were less reclusive when it came to making an entrance. The head of the house was responsible for the morals of his entire household and until the first quarter of the 18th century, the word family included servants, so on Sundays a whole raft of people would turn up.

“In a way it would have been a bit like a pop star today turning up with an entourage,” says Dawn.

We don’t know who the pews were rented by, because there are no signs of brass plaques and no records survive. But look carefully and you will find one with a pair of merchant’s marks that suggest ownership. Another rarity at Holy Trinity is the stone altar. Most examples disappeared during the Reformation, but this one escaped and although the limestone is broken, four of the five consecration crosses can be clearly seen.

Then there is the hagioscope or squint, an angled window built into the chapel wall that was used by a chantry priest to say mass in synchronisation with the priest officiating at the high altar. Again, this is unique in York.

Other curiosities include a pair of grandfather clock-shaped boards which record names of York Lord Mayors, including ‘railway king’ George Hudson. And they had their own elevated pews, where they could sit head and shoulders above the rest of the congregation.

“It was a big thing having the church graced by the Lord Mayor,” says Dawn. “I think it’s immensely interesting they chose to record a period of time when someone from this parish was mayor on something in the shape of a clock.”

Other things worth mentioning are the 15th-century font, which, although plain, has an unusual goblet shape, and an oak front cover added in 1787.

Then there is the 13th-century carved grave slab which was excavated from the south east chapel. It is decorated with a floriate cross and rebus showing a fish and cauldron, indicating that the deceased would have been a fish monger.

Indeed the whole floor is made of grave stones, including those for Lord Mayors and even the groom of the bed chamber to Charles II.

“To be buried in a church is to be nearer to God,” says Dawn. “Especially so close to the altar, which is where the nobility were laid to rest.”

The splendid Georgian altar cloth, seen here in the picture from the 1906 guide, is the only missing piece from this unspoiled jigsaw.

It was destroyed by a fire in 1981, despite the valiant actions of Dorothy Jelks, an American tourist, who fought her way through the smoke, trying in vain to save it. At least she was able to get to a shop and raise the alarm.

Dorothy’s actions undoubtedly saved Holy Trinity Church and thank goodness for that, because it really is a gem. One that offers tantalising clues throughout, but ultimately leaves you intrigued and with more questions than answers.

• Holy Trinity Church, 70 Goodramgate, York Tel: 01904 613451

• Holy Trinity is open to visitors and still used for Christian worship at least twice a year. It features in a new book Beautiful Churches Saved By The Churches Conservation Trust, by Matthew Byrne, published by Francis Lincoln Limited. For more information visit visitchurches.org.uk/BeautifulChurchesBook

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel