The life of an extraordinary York explorer will be celebrated in an exhibition at the Yorkshire Museum that opens next weekend. STEPHEN LEWIS reports.

IF YOU were going to write a boy’s own adventure about a daring explorer, you’d want to make sure he had a great name. Indiana, perhaps. Or Captain Nemo. Or what about Challenger (as in Professor Challenger, the irascible Victorian adventurer from Arthur Conan Doyle’s Lost World)?

Or here’s an even better one: why not christen your dashing hero Tempest? It’s a name that calls to mind thunderstorms and wild places; it hints at passion, a fiery temper, and above all strength and fearless courage.

In fact, there was a real-life Victorian explorer who really was named Tempest: and he was from right here in York.

You’ve all heard of the Tempest Anderson Hall. But how much do you know about the man it’s named after?

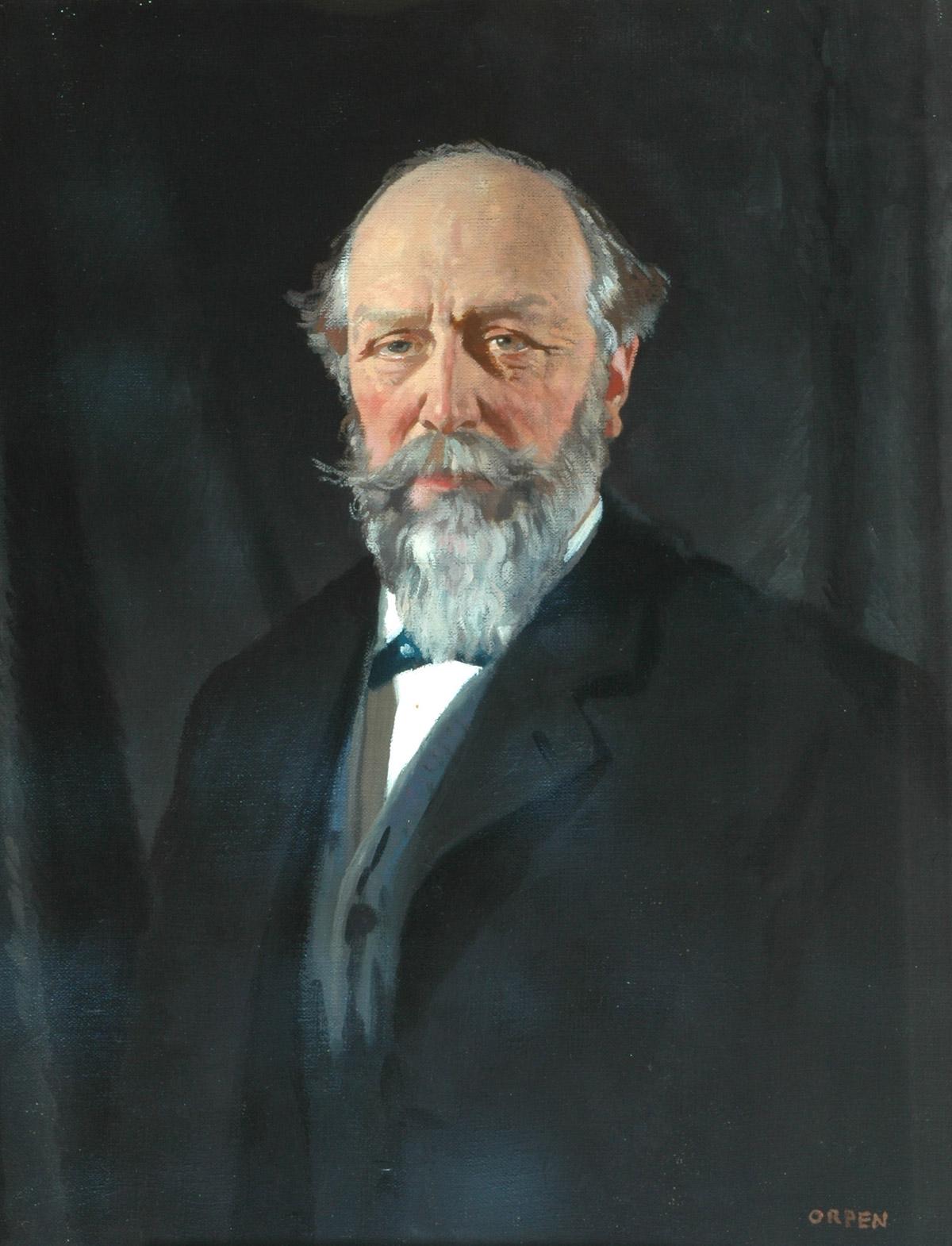

Tempest Anderson was extraordinary. A York doctor who specialised in diseases of the eye, from the 1880s onwards he spent much of his life travelling the world, chasing (and photographing) exploding volcanoes. He witnessed them all – Vesuvius, Krakatoa and, in 1902, the eruptions that devastated the islands of Martinique and St Vincent in the West Indies.

He was said to have always had two bags packed in the bedroom of his York home – one full of clothing for warm climates, one full of clothing for cold, so that he could leave at a moment’s notice.

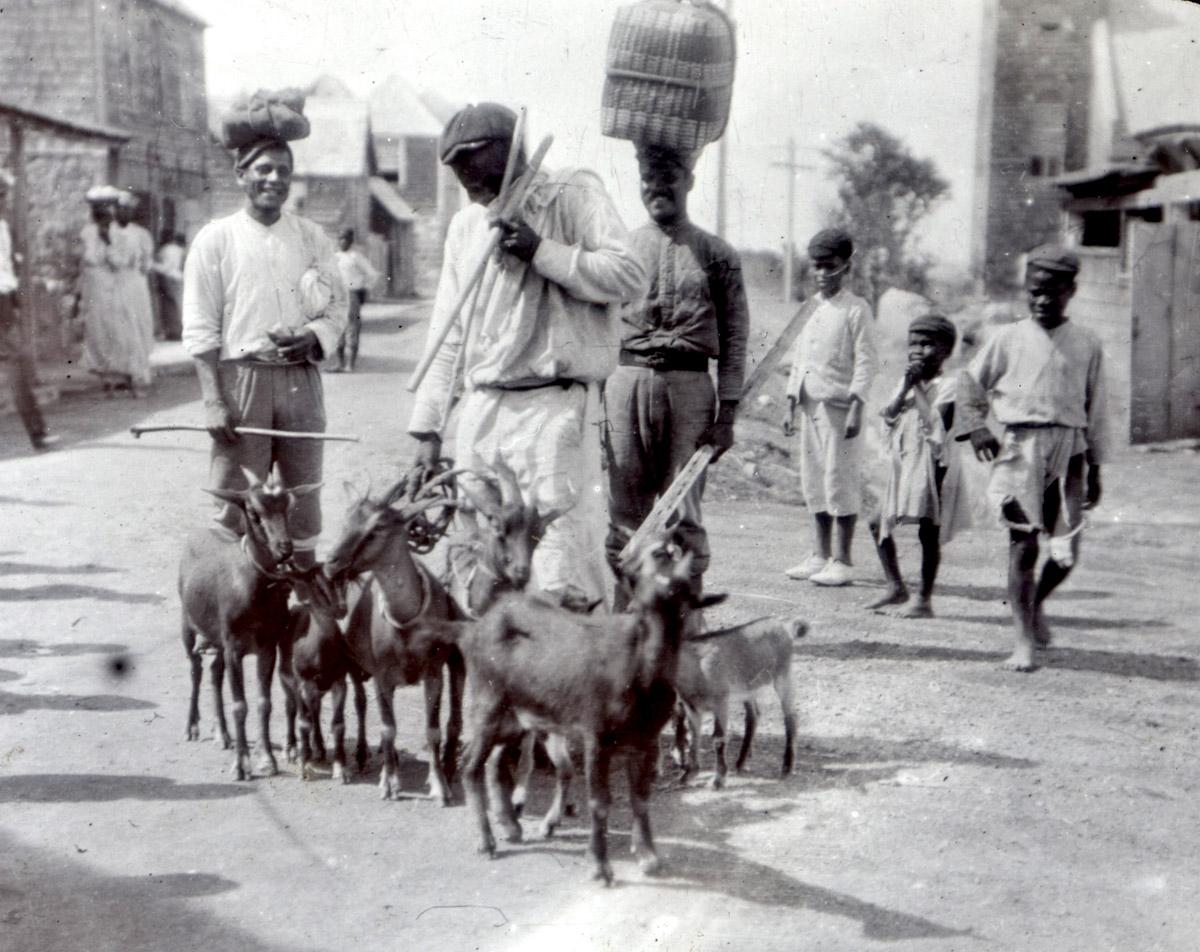

He frequently put his life at risk by venturing up the very flanks and into the mouths of active volcanoes. And during the course of his travels he took thousands of photographs – of volcanic explosions; of his camps and bivouacs; of the indigenous tribes and peoples he met – and used them to give ‘magic lantern’ shows to enthralled audiences back home in York and across the UK.

“He was an extraordinary man,” says Stuart Ogilvy, assistant curator of natural sciences at the York Museums Trust. “He was one of the most colourful characters in York at the time.”

He was almost, Mr Ogilvy says, the David Attenborough of his day. There was no TV back then. Through his magic lantern shows, Dr Anderson gave his audiences a glimpse of a world, of peoples and places, they’d never otherwise have seen.

He was incredibly well known in his lifetime. “And yet now his life is shrouded in mystery,” Mr Ogilvy says. “There are few people in York who know who he was.”

That’s all about to change. Next month marks the 100th anniversary of Tempest Anderson’s death. And to mark the occasion, the Yorkshire Museum is putting on a small exhibition dedicated to his life and work.

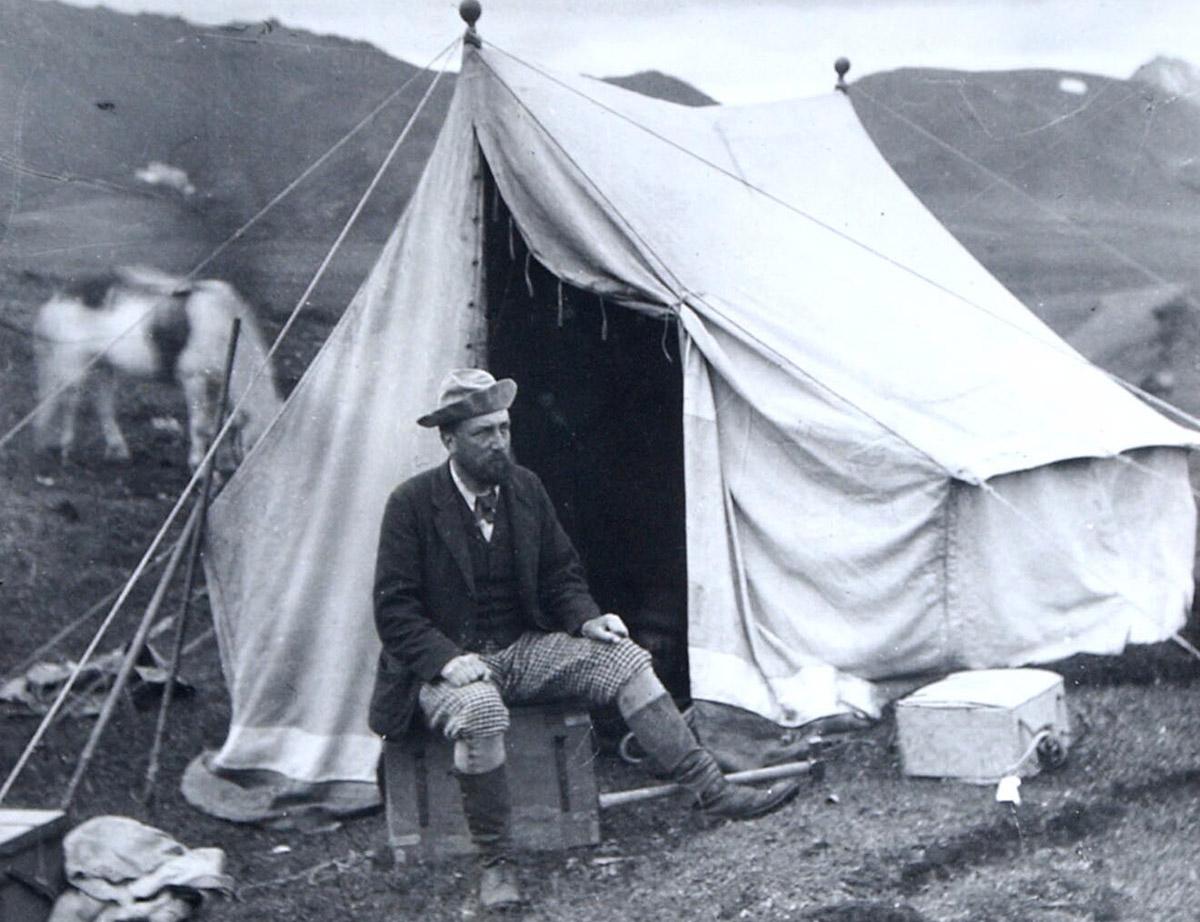

Tempest Anderson: Volcano Chaser features a selection of some of his most breathtaking photographs. There are pictures of the man himself on his travels, including one of him sitting in front of his tent during an expedition to Iceland in 1890; photographs of members of his exhibition picking their way up the flanks of devastated mountains where all life has been blasted away in volcanic explosions, leaving just the shattered trunks of trees behind; pictures of the exotic indigenous peoples he encountered in the course of his travels from the West Indies, to Mexico, South America, Canada and the Far East.

Not since the 1970s have many of these photographs been put on show. They will be joined, in the exhibition, by some of the ash samples Dr Anderson collected on his travels – and by examples of the kind of equipment he would have taken with him, including a pinhole camera, a travel bag and a pocket watch.

“It will be a fitting tribute to one of York’s most renowned explorers,” Mr Ogilvy says.

And not before time.

• Tempest Anderson: Volcano Chaser opens in the Reading Room on the first floor of the Yorkshire Museum next Saturday.

The adventurous life of a man called Tempest

Born in York in 1846, Anderson was christened ‘Tempest’ not because of his fiery temper, but after an eminent West Yorkshire family of the same name who were related to his father.

He went to St Peter’s School, then studied medicine at University College, London, before returning to York to work in his father’s medical practice. He specialised in ophthalmic medicine, and also worked at York County Hospital.

A keen mountaineer, he became interested first in glaciers, then volcanoes.

By 1890 he had visited and photographed most of the European volcanoes, and become known as an amateur vulcanologist.

His greatest scientific contribution to volcanology came in 1902, when he witnessed eruptions on the islands of Martinique and St Vincent in the West Indies and, in a major scientific paper, compared them to avalanches he had seen in the Alps.

Back home, he became a prominent figure in York; giving magic lantern shows, becoming a pioneer of town planning, and serving a term as Sheriff of York in 1894. He was also the first man in York to have a telephone: his number was York 1.

His last trip abroad was to Indonesia in 1913, where he witnessed (and photographed) the eruption of Krakatoa. On the voyage home he became sick with heat apoplexy and enteric fever, died on board ship in the Red Sea on August 26, 1913, and was buried at Suez.

Dr Anderson never married. On his death he left half his estate to the Yorkshire Philosophical Society, the founders of the Yorkshire Museum.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel