Jim Porteous was one of the last generations of Britons to have been struck down by polio. He spoke to STEPHEN LEWIS in the wake of Bill Gates’ pledge to eradicate the disease for ever.

ONE of Jim Porteous’s most vivid memories is of being loaded on to a train at the age of six. He’d been struck down by polio a few months before.

Paralysed from head to toe, conventional treatment at the time recommended that his body should be immobilised. So he’d been encased from neck to ankles in a rigid plaster cast.

He was on his way to a hospital in Surrey which offered a pioneering new treatment that Jim’s father, William – a manager at Rowntree’s in York – had heard about while on a business trip in the US.

But getting the little boy on the train wasn’t easy.

It was 1953. The train had those old-fashioned coaches with corridors running down the side. “They couldn’t manoeuvre me, and had to take the windows out of the train in order to shove me through,” recalls Jim, now 66.

He’d contracted polio the year before. The family – Jim, his parents and his sister – had been for a seaside holiday in the North East. When they got back home to York, he was feeling unwell. “I had a temperature, a headache, and I was feeling just run down and very poorly.”

The family GP diagnosed him as having poliomyelitis, a viral infection that can cause paralysis, breathing problems and even death. There was a lot of it about in 1952 when the country was in the grip of one of the last polio epidemics.

In the early stages the illness was infectious. Jim was rushed to York’s Yearsley Bridge Isolation Hospital. What happened next must have been horribly frightening. “Over a few days, I lost the use of my arms and legs and my whole body,” he says. He even lost the ability to breathe by himself, and had to be placed in an iron lung.

He remembers his parents coming to see him. He couldn’t move a muscle. “The only way I could see them was through a mirror that was above me.”

He doesn’t remember feeling frightened: but looking back he can imagine what it must have been like for his parents. “It is only since I have been an adult and had my own children that I have realised what trauma my parents must have been through.”

Jim was encased in the plaster cast in which he was to remain for six months. Once his illness had passed the infectious stage, he was moved to the Adele Shaw Hospital for seriously disabled children at Kirbymoorside. Then his father heard about the new approach to treating polio.

This was known as the Kenny Method, after the Australian nurse who devised it. Instead of immobilising patients’ bodies with plaster casts and cumbersome leg braces, it advocated hot compresses to ease muscle spasms, and gentle physiotherapy to get paralysed muscles moving.

After enduring the indignity of being shoved through a train window like an item of parcel post, Jim spent four years at the hospital in Surrey.

It was a surprisingly cheerful time of his life, he admits. There were between seven and ten children on his ward, all severely disabled. But they were all “reasonably bright and breezy”, he says: and they all had fun, paddling their beds around the ward as though they were in punts on the River Cam. He joined the cubs, and he had visits from a succession of new ‘uncles’: members of the local rotary club his parents had asked to befriend him.

After four years, his breathing was better, and he had recovered the use of his arms.

He was able to return to his family in York, where he tried to learn to walk with callipers.

Eventually, he had to reconcile himself to life in a wheelchair. In fact, he cannot remember ever being able to walk properly, although there must have been a time when he could. “I have seen pictures of me standing. But I don’t have any memories of it.”

A bright, outgoing boy, he was determined not to be defined by his illness. He’d missed four years of schooling, but still managed to pass his eleven-plus at the second attempt. “I think I’m one of the few people that has ever sat the eleven-plus twice.”

Schools in the 1950s were not geared up to take children with such severe disabilities. In fact, only two in the country agreed to accept him. One was Gordonstoun in Scotland, where Prince Charles went. The other – to its enormous credit, Jim says – was Archbishop Holgate’s School, here in York. He chose the latter, then still based in Lord Mayor’s Walk.

He had many friends at the school, where he engaged in the usual schoolboy pranks. His friends would carry or push him wherever he needed to go. He joined the Scouts and one of the tasks his fellow Scouts were set was to get him to the top of York Minster.

“I was strapped to a stretcher and they carried me up the central stairway right to the top. Then they stood the stretcher on end so I could see the view.”

He learned to swim, with the help of a woman named Gladys Smith at the Yearsley Baths. It was a bit of a comedy of errors at first. His legs and tummy were more buoyant than his head and shoulders, so he ended up with his bottom in the air and his head below water.

Mrs Smith experimented with various solutions and eventually developed a pair of ‘flippers’ he could wear on his hands. It meant he could swim. “Although I looked a bit like a frog!”

With the help of a rigorous exercise regime at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in his mid-teens, he even managed to qualify for the British Paralympic Swimming Team – although in the 1960s, it wasn’t all that difficult, he jokes.

He did well at school and on leaving ‘Archies’ at 18 managed to get a traineeship with a local firm of stockbrokers. After a couple of years, he left to join his father’s company, Rowntree’s – and spent the next 33 years with the company, rising to become Nestlé’s head of trade communications. Since retiring in 1999, he has run his own business – Notions – from an office at his home in Hessay.

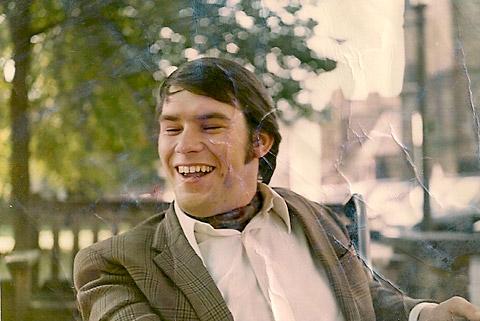

He has had an extraordinarily rich and full life, he says: travelling the world, marrying and having children. As a young man, he wore a cravat and drove a bright orange MGB GT roadster, adapted so he could drive it with his hands. He managed a number of York bands in the 1960s, organising gigs at local pubs.

Later in his life, he became a pillar of the York establishment, sitting on the board of the Prince’s Youth Business Trust, becoming a member of the York Crime Prevention panel, acting as chair of governors of York’s special schools, and most recently being elected a governor of York Hospital. He has an MBE for services to charity: just the most recent of several occasions on which he has met the Queen.

But he has never forgotten the people who gave him a chance: his family; Gladys Smith, who taught him to swim; Donald Frith, the headteacher of Archbishop Holgate’s, who offered him a school place; Peter Hawley, who accepted him into the 1st Huntington Scouts; Rowntree’s, which gave him a job.

“They were all prepared to say: if he thinks he can do it, let him do it,” Jim says.

He’s spent the past 50 years proving they were right.

"I’m a husband and father, and I hope a fairly considerate friend and businessman, first"

Jim Porteous has been determined all his life not to let his disability define him.

“I don’t see myself as being primarily disabled. I’m a husband and father, and I hope a fairly considerate friend and businessman, first.” In fact, he says, his illness has in some ways made him a better man. “I think it has made me more tolerant of people’s needs.”

But now, as he gets older, he is beginning to find some of his old symptoms returning.

He needs a respirator at night to help him breathe and has pain in his hands.

He’s not alone. His condition is known as Post Polio Syndrome, he says, and there are as many as 120,000 people living with polio in the UK today who could potentially develop it.

They are all, like him, members of the last generation of British polio victims – the polio vaccine became widespread not long after he himself contracted the disease.

No one quite knows what the future holds. Doctors have little experience of the condition because it virtually disappeared in the UK in the 1950s. But there is help out there, he says.

He is President of the Yorkshire region of the British Polio Fellowship. There are branches in every major town. The symptoms cannot be cured, but they can be alleviated by certain activities and exercises. And by joining the Fellowship, you will be assured of support from other people out there like yourself, he says.

“There are a lot of people who had polio who have never spoken to another person who had polio.”

To find out more about the British Polio Fellowship, call 0800 018 0586, or visit britishpolio.org.uk

Bill Gates determined to eradicate disease

POLIO is a highly contagious viral infection that can lead to paralysis, breathing problems and even death. It attacks the neurons in the spinal cord, causing paralysis in the arms and legs, and breathing problems.

It was widespread until the first polio vaccine was invented in 1952, since when it has been eradicated in much of the world. A quarter of a century ago, there were still 350,000 new cases worldwide. Last year, there were only 205.

But the disease still persists in three countries: Pakistan, Nigeria and Afghanistan.

In his recent Richard Dimbleby Lecture for the BBC, Microsoft billionaire Bill Gates spelled out his determination to eradicate the disease for ever.

“Polio eradication is a proving ground, a test,” he said. “It will reveal what human beings are capable of, and suggest how ambitious we can be about the future.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here