The Minster’s Book of Remembrance may be a well-known tribute to York’s war dead, but resting quietly in a locked case is an extraordinary memorial to those killed in the Great War. MATT CLARK reports.

STREAMS of red and blue light from the Five Sisters window shine across the pages of the King’s Book of York Heroes in the Minster as Vicky Harrison leafs through a seemingly endless parade of young faces.

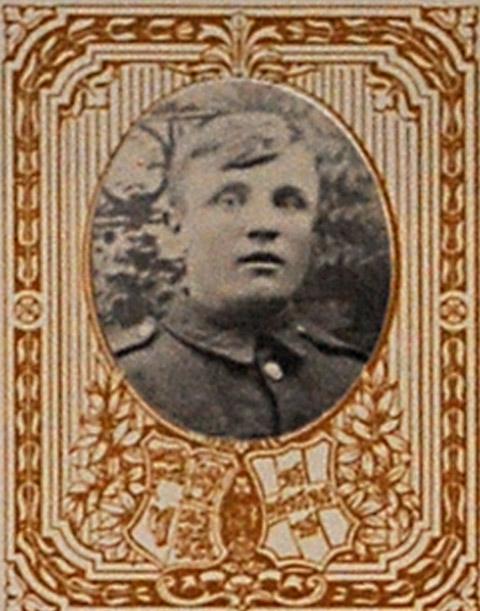

She stops at page 53 and at the top is a fresh-faced, fair-haired 22-year-old called Walter Robinson.

Walter was a member of the 10th West Yorkshires, a ‘Pals’ volunteer regiment, who had answered Lord Kitchener’s call to arms in 1914. His unit spent two years training in Britain and their first offensive was part of a move in 1916 to relieve pressure on the French at Verdun.

It was 7.30am on July 1 when whistles blew to begin the Battle of the Somme. Then, after an exchange of shells, all fell quiet as the Germans manned their positions.

A few yards away British commanders were instructing their men to march in formation through no man’s land and on to attack enemy lines.

But as the advance began, so did the machine guns, and the slaughter. By day’s end the British army had suffered its greatest single loss in history – 20,000 soldiers lay dead; Private Walter Robinson was one of them.

“When I sift through the book, everyone looks an awful lot younger than me,” says Vicky, who is the Minster collections manager. “It’s my 30th birthday this week and I don’t feel I’ve had a chance to live yet.”

The conflict was meant to be the war to end all wars and across the country men, like Walter, rushed to sign up. Lads lied about their age to join the action and Lord Derby’s ‘Pals’ battalions whistled as they marched, full of good humour and patriotic fervour.

It would all be over by Christmas and while eating turkey roast, war heroes could regale their loved ones with tales of derring-do for King and Country as they toasted in a new golden age for the British Empire.

Lance Corporal James Hamilton, of Acomb Road, York, didn’t get to regale his loved ones. Nor did he survive his first battle. James was killed in October 1914 at The Battle of Messines.

He was 25 years old and one of the first York men to die in the Great War.

But his name lives on in the King’s Book of York Heroes which lists the city’s 1,443 residents who were killed in the conflict.

Two feet long and nine inches thick, it weighs nine stones and is one of the largest books on earth.

Edwin Ridsdale Tate was commissioned to design the book in 1920. And he didn’t stint on the detail. The cover is sumptuously carved oak. Inside, pages are exquisitely laid out with copperplate edging and there is a lavishly decorated dedication page.

The book includes Captain Arthur Gordon Kilby, who won the Victoria Cross and whose ancestors included Archbishops of York.

Captain Kilby was killed in action at the Battle of Loos on September 25, 1915. At his own request, Kilby led a charge of men in the face of heavy machinegun fire and a shower of bombs.

He didn’t stand a chance.

“I think the particular thing is that everyone listed in the book lived in York,” says Vicky. “I can imagine them walking down Leeman Road or Goodramgate and seeing the same things I see. That gives it a real context.”

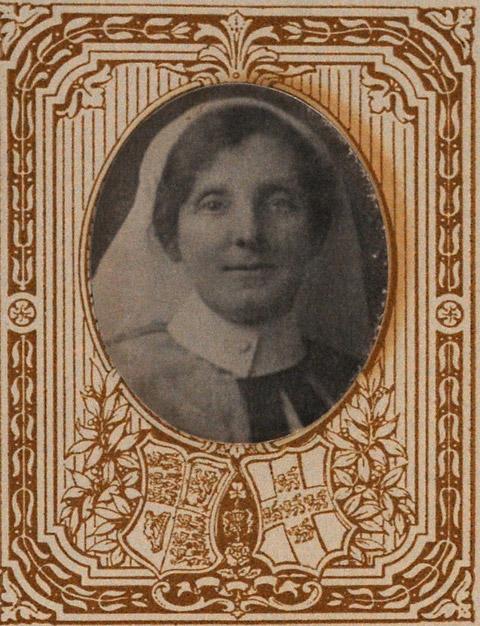

While the book is almost entirely full of men, two of those remembered are women. Eveline Hodgson, a military nurse, died in Salonika, Greece and Betty Stevenson of the YMCA was caught in the open during a German air raid in Etaples, France.

Vicky has a citation which describes them as “brave, bright and fearless girls; real heroines of the war”, adding “it is a singular coincidence that both these ladies were connected with Burton Stone Lane, York”.

Sometimes relatives ask to see the entry for their own war hero and Vicky says that helps to bring the stories to life.

“I always feel it’s a special moment for the family and quite often there are a lot of emotions. I know the entry, but until you see it through someone else’s eyes you don’t really appreciate what it means.”

Information for the King’s Book of York Heroes was supplied by friends and family and a certain Mr Adams of the Yorkshire Evening Press was charged with collecting and arranging the portraits as well as writing the obituaries.

The book was received into the Minster two days before the second anniversary of the Armistice. Four months later it was taken to Buckingham Palace to be signed by King George V.

“This is an important record of York,” says Vicky. “Although it has so much decoration and is one of the biggest books in the world, it’s actually a very quiet book. It doesn’t shout for attention and to me that seems appropriate.”

Although the roll was of honour was thought to be complete, Ridsdale Tate left an appendix of blank panels so that any men who subsequently came to light could be honoured.

Vicky is researching the story of one of them. Frederick Maskell of Lincoln Street died on July 25 1917, aged 19, as a result of gas poisoning.

Frederick will soon be included in the King’s Book of Heroes thanks to one of his relatives who contacted the Minster Library. Vicky says if anyone feels an ancestor has been missed, they can supply the information and she will do the rest.

“Each entry builds a little picture,” says Vicky. “There are names from all the big battles here and this book is like a time capsule of the First World War, seen through a snapshot of York.”

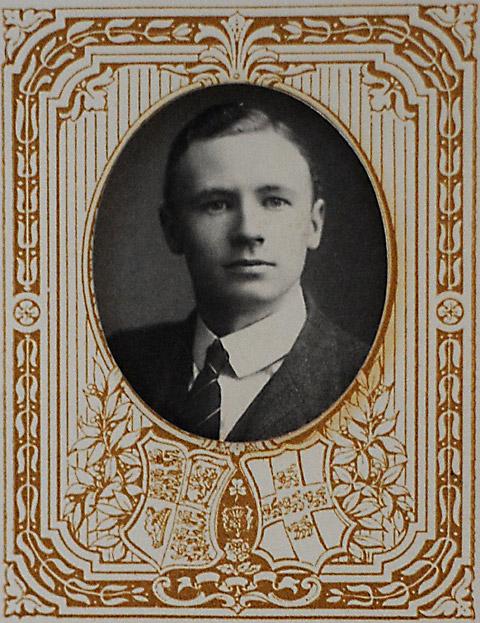

The roll call of the fallen was placed in alphabetical order and all but seven have portraits. That, says Vicky, helps her to connect with them more than a list of names on a war memorial.

And they also have a resonance with the present day.

“These are the same sorts of photos and the same sorts of uniforms you now see in the newspaper. A hundred years on and we are still doing the same thing.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel